Building on our research series exploring public narratives and attitudes towards refugees and other migrants, ODI Europe, together with the Spanish Foundation porCausa and the Democracy and Belonging Forum held an event Where to next on migration for southern Europe? Analysing trends in narratives and policies this month at the CaixaForum in Madrid.

Southern Europe’s hyper-securitised border control measures have been implemented in a context of stigmatising and discriminatory political rhetoric towards migrants. This rhetoric, which is increasingly out of sync with public attitudes, has gone hand and hand with more regressive policies. Bringing together researchers with practitioners, we discussed these latest trends and how civil society can help facilitate a more constructive debate on migration across the region.

Here we share our key learnings from the event – which is now available to watch below (a Spanish recording is also available).

Long-term trends in public attitudes on migration in southern Europe

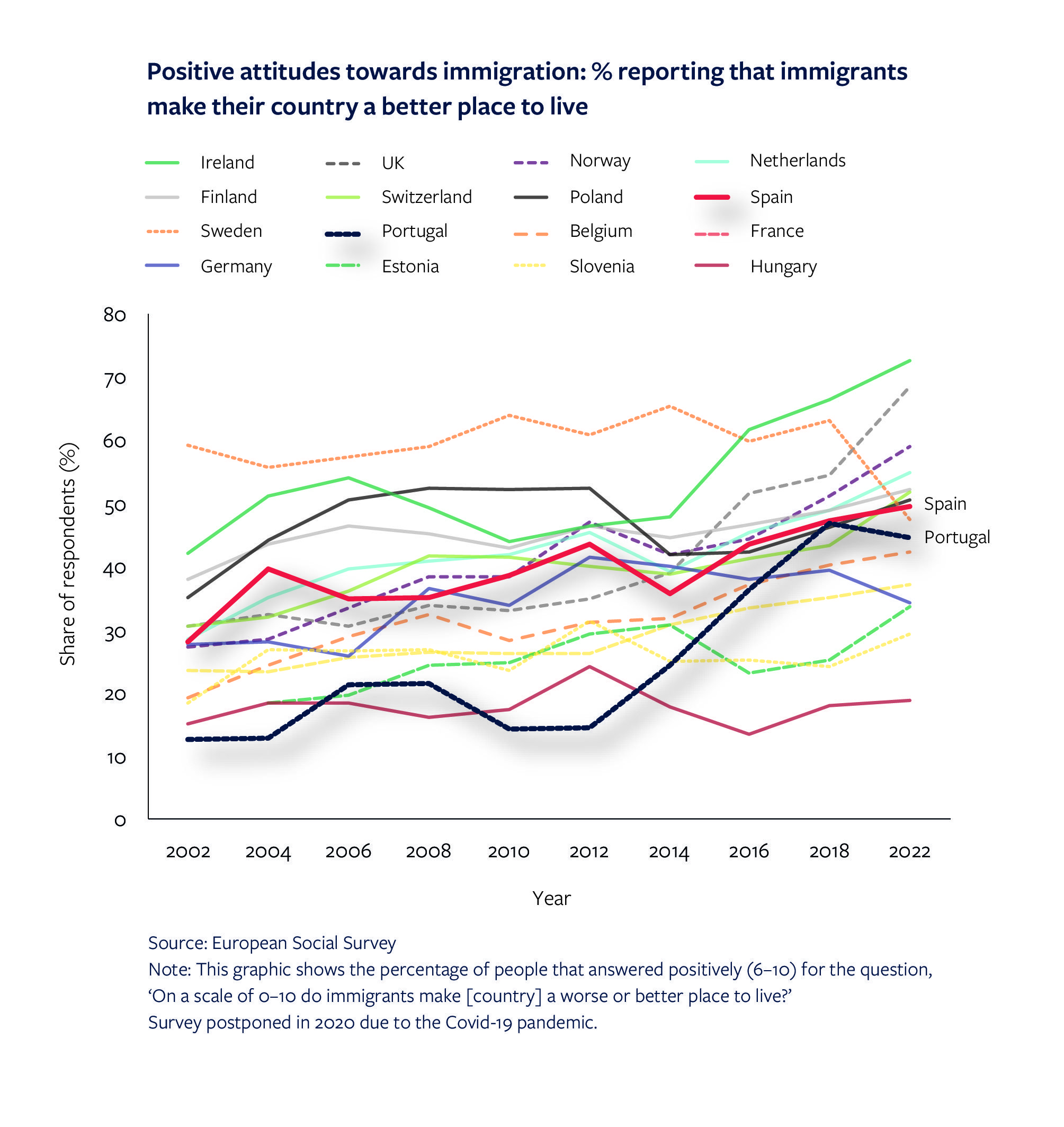

Survey data shows public attitudes towards immigration are increasingly positive (with a few notable exceptions like Sweden) across the continent. As this graphic shows, both Spain and Portugal sit squarely in line with broader, long-term trends in this area across Europe.

Italy and Greece are well known for their more negative public attitudes around immigration. In the latest round of the European Social Survey, only 34% of Italians felt immigrants made their country a better place to live (scoring the impact of immigration at six or above on the 0 to 10 ‘worse-better’ scale). Much lower levels of positivity are recorded in Greece.

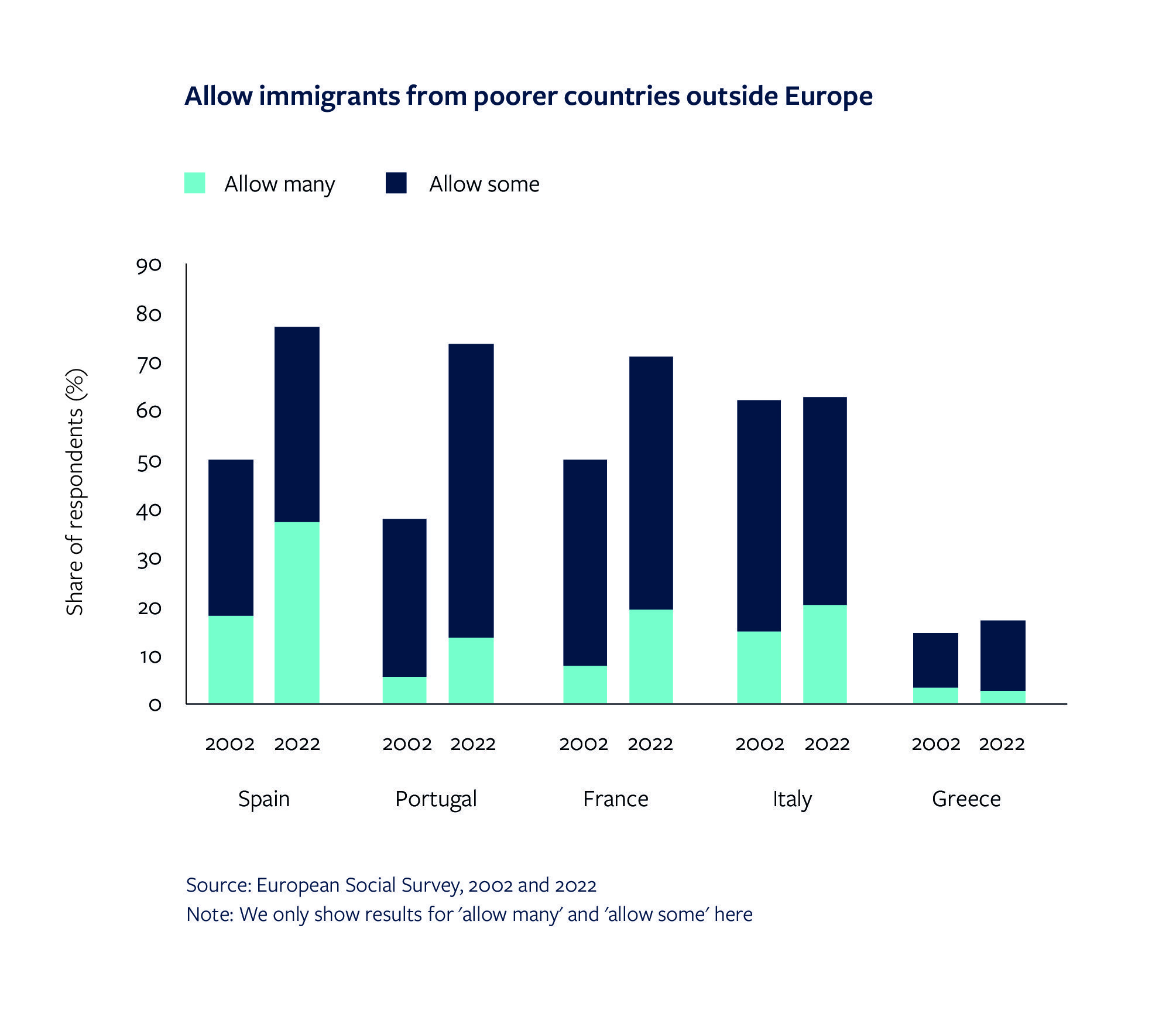

While we often lump Greece and Italy together – given the hostile narratives and harsh deterrence-oriented policies seen in both countries – this does not mean public attitudes are similar. In fact, Italy has more in common with Spain, Portugal and France in its polling results, as this figure shows.

It is perhaps not surprising that – in public attitudes terms – Greece remains a negative outlier. The country suffered the worst economic crisis of all Western nations following the global financial crisis and has struggled with exceptionally high numbers of arrivals of refugees and other migrants (over 850,000 sea arrivals in 2015). This, combined with the shortcomings of the EU's regional system for refugee-hosting, has left the country shouldering a large burden.

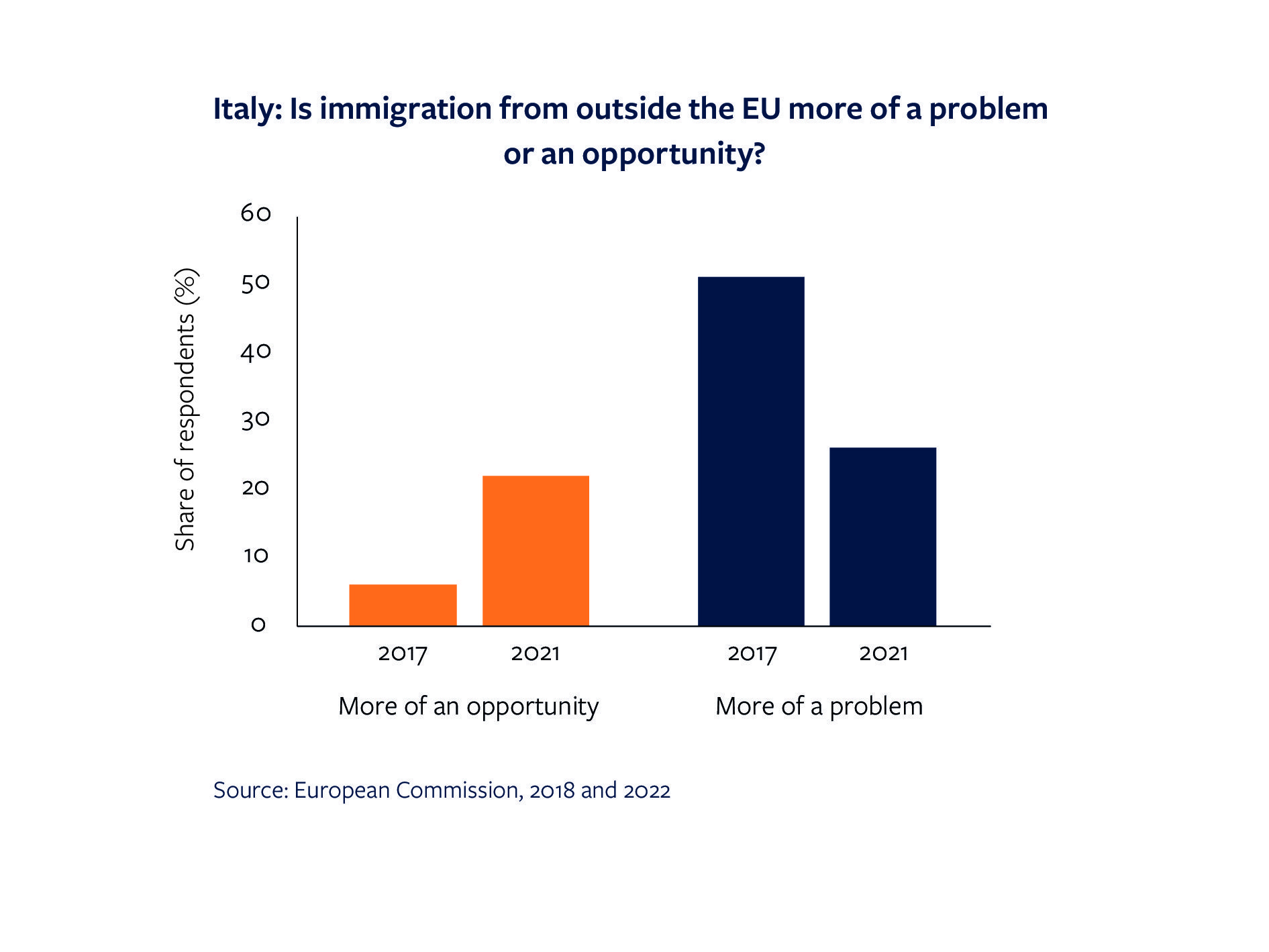

What may be going unnoticed, however, are the major shifts happening with public perceptions in Italy. One illustration can be found in Eurobarometer data when Italians are asked if they see migration from outside of the EU as ‘more of a problem or more of an opportunity.’ Results show a major shift on this question:

In fact, this is the most dramatic change on these indicators – across a notably short time period – across all EU countries surveyed.

Efforts to change narratives around migration

Our gathering in Madrid provided a platform to showcase the myriad efforts by civil society across southern Europe to place the stories of migrants at the front and centre of policy discussions and to challenge negative and divisive rhetoric. For example, porCausa's work

in Spain has brought a more humane and nuanced message by both engaging with what drives people’s fears and mobilising migrants to use their voice.

The actor and activist Thimbo Samb emphasised the importance of migrants telling their own stories. He rejected one-dimensional narratives that highlight ‘sadness and pain’ and the traditional ‘paternalism or victimhood’ framings which underlie so much content creation. His own efforts include the upcoming documentary film, Cayucos de Kayar, which traces his journey from Kayar in Senegal to Madrid in search of a better future.

The activist and human rights defender Ismail El Majdoubi cautioned against asking migrants ‘to be heroes’. He called for a wider approach that goes beyond the story of migrants’ journeys, and enables a better, fuller understanding of why people move, as well as more investigative journalism on 'what is out of sight' such as the detention of child migrants.

Indeed, we clearly need more nuance and sophistication in presenting migrants’ stories, ensuring they are not simplified down to stereotypes such as the ‘victim or villain’. The panel rejected narratives of threat and hate and called on civil society to resist ‘following the agenda of securitisation set by politicians’ and instead to set their own long-term agenda with narratives of hope, community, humanity and belonging.

The failures and contradictions of migration policies

Many of our panellists highlighted the structural contradictions inherent in debates and policies around immigration.

Eleni Takou reminded us of the pressures on Greece, ‘to deter people, to be the “shield of Europe”, but at the same time to provide good reception conditions or be punished.’ And while deterrence is strongly encouraged, Greece ‘must push people, but not actually push them back.’ Antonella Napolitano talked of the paradox that results from the increasing use of border surveillance technologies: ‘governments in fragile states and authoritarian regimes use these new tools of surveillance to further repress dissent. But this fuels more instability and out-migration'.

Deterrence policies were widely critiqued, an area of well-known policy failure. What better illustration than from journalist Aida Alami: ‘I talked to one migrant and he told me “when I went into that water, I knew there was a 90% chance I would die. And I went anyway.”’ The human cost of failed migration policies is never far from the agenda of these events.

And for all the talk of deterrence and hostility towards migrants, what we all know is both how much Europe desperately needs workers and how developmental migration from poorer to richer countries can be. Both our Italian and Greek panellists pointed clearly to the contradictions between the hostile rhetoric in public that co-exists with (quietly implemented) regularisation schemes in Greece and increases in non-EU work permits in Italy.

What gave us hope?

We took time to celebrate the positive campaigns, as in Italy, where civil society campaigns for citizenship reform have raised awareness amongst the public about the negative impacts of restrictive legislation. Another Italian example, of churches, labour unions and civil society groups coming together in an impressive, broad-based coalition, caught the attention of Spanish activists. The coalition’s effective campaigning – around a five-point policy agenda spanning regularisation, decriminalisation and other aspects – demonstrated the power in coalitions to mobilise, inform and create change.

And we welcomed hearing from Amparo Gonzalez-Ferrer about the Spanish government’s efforts to resist hostile political narratives and find the space for inclusive immigration policies attuned to labour market demands. Indeed, Spain’s focus on offering (on a permanent basis) a clear path out of irregularity sets it apart from other European countries.

We also heard about the creation of MedMA – the new Mediterranean Migration and Asylum Policy Hub. Based in Greece, but connecting with researchers, practitioners and activists across southern Europe, the new policy hub aims to make constructive proposals for legislative reforms tailored for the Mediterranean region.

And finally, in a topic often dominated by negativity, the positive trends in public attitudes towards immigration was a major reason for hope.

“Where to next on migration for southern Europe?”

— Antonella Napolitano (@svaroschi) October 5, 2023

We start with @ClaireKumar3 showing data on public attitudes towards migration - much more positive than the heated debate suggests.

Thanks for organizing @porCausaorg @ODI_Global @oandbinstitute pic.twitter.com/UFdsqePpMg

While evidence is mixed about what drives attitudes to immigration, 20 years of European Social Survey data may be showing us the impact of generational change. The European public are emphatically not the constraint for more sensible and humane immigration policy design in most countries.

However, our political leaders – who tend to focus on issue salience – seem oblivious to the reality of public attitudes and continue sleepwalking into the far-right trap, allowing hostile rhetoric to become mainstream. They should take note: have the courage to embrace more humane and effective immigration policies, or risk becoming increasingly out of touch.