We are used to seeing Nordic countries topping global rankings thanks to their stable democracies, generous welfare policies and commitments to equality. But when it comes to immigration, Denmark – and more recently Sweden – appear intent on modelling more regressive approaches. ODI’s new research traces Denmark’s transformation from a tolerant, open nation to a country that has embraced increasingly restrictive policies and highly polarised rhetoric around immigration.

The Danish Transformation

Three decades ago, Denmark’s immigration policies were amongst the world’s ‘most people friendly’, with asylum requirements eased in 1983 and expansive family reunification rights established. By the 1990s more restrictive immigration policies started to take shape as debates around immigration grew and anti-immigrant rhetoric took hold. The really significant ‘paradigm shift’, however, has emerged since 2015, when Danish immigration policy moved from a focus on settlement and integration to detention and return. In fact, between 2015 and 2018, Denmark amended its immigration policies no less than seventy times as immigration became a focus of far-right attention.

This has had major impacts. The strong focus on ‘deterrence’ has translated into efforts to make Denmark as unattractive a destination as possible for asylum seekers. Conditions in Danish detention centres are dire, with practices including solitary confinement and other highly criticised disciplinary techniques. Cuts to benefits have targeted refugees. And a controversial 2016 policy allows the government to seize refugees’ assets to cover the cost of reception.

Is Sweden embracing the Denmark model?

While Denmark has been on this path for several decades, Sweden has maintained fairly open immigration policies until much more recently. It is one of the few European countries which provides immediate rights to work for asylum seekers and, after Canada, it has taken in the most resettled refugees in the world relative to its population size in recent years.

But Sweden’s traditional openness is shifting, notably after the arrival of large numbers of Syrian refugees in 2015. Since then, welfare benefits have been reduced and opportunities to be granted permanent residence have decreased.

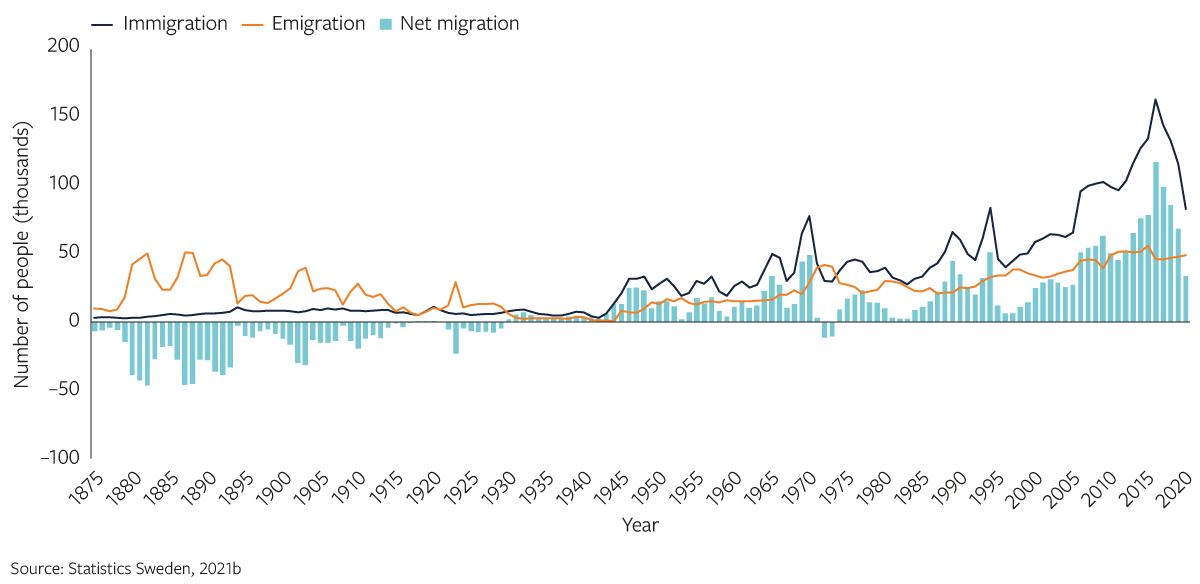

Long-term migration trends in Sweden

The most significant changes in Sweden, however, are only now emerging. The new Tidö Agreement proposes a reduction in family reunification rights and to dramatically reduce the quota of refugees coming to Sweden from 5,000 to 900 – a major blow to the global refugee resettlement effort given Sweden’s leading contribution. It also proposes new conditions that will restrict access to benefits for newly arrived immigrants.

Threat narratives and the rise of the far right

These regressive reforms in both countries have been accompanied by narratives that stoke fear of refugees and other migrants. In Denmark this is an old story. As far back as the 1970s and 80s rhetoric presented immigrants as a drain on the welfare system and refugee arrivals as an ‘invasion’. The far-right Danish People’s Party (DPP) – created in 1995 – grew out of this increasingly nationalist and anti-immigrant environment. It successfully attracted increasing numbers of voters by emphasising the threat posed by immigrants (and particularly Muslim immigrants) to Denmark’s cultural values, security and welfare system. By 2015 the DPP was the second largest party in Parliament.

In Sweden, the rise of the far-right is more recent. After major efforts to move from the fringes – given their association with white supremacy – the Sweden Democrats managed to increase their vote share to 20.5% last month. They now hold significant influence in Parliament with the chairmanships of four parliamentary committees. As in Denmark, the party presents immigrants as a threat to the welfare state, a drain on public resources and responsible for increasing crime rates.

The left moving right

But this is not simply a far-right story. The response of left-wing parties is critical in understanding the evolution of political narratives and policy reforms. In Denmark a major shift came in 2001, after the landmark election loss of the left-wing Social Democrats. Clearly fearing that they were losing their electoral base due to their stance on immigration, their response has been to not only embrace the narrative – as demonstrated with their vision for “zero asylum seekers” – but also to adopt highly restrictive policies. It is the Social Democrats who proposed the highly controversial law to externalise the processing of asylum seekers to third countries (like Rwanda) and declared parts of Syria safe for return (a policy which has led to hundreds of Syrians already settled in the country being picked up and detained pending return).

And let’s acknowledge the fact that this strategy has been successful. The DPP’s electoral influence has all but disappeared while the Social Democrats gained their best electoral result in several decades in November (though the party still faces a new far-right force, given the Denmark Democrats won 8% of the vote in the recent election).

Do threat narratives gain traction with the public?

The anti-immigration threat narratives in both Sweden and Denmark have gained traction with the public, who have become fearful that refugees will commit crimes.

But these perceptions do not match up with reality. In a Danish survey exercise, when informed that 5.4% of young male immigrants with a non-Western background had been convicted of a felony in 2012, respondents estimated this had risen to 20% in 2019 when it had in fact fallen to 3.5%. The gap is even more pronounced amongst far-right supporters, with DPP voters estimating a rise to 30%.

What do public attitudes regarding the impact of immigration tell us?

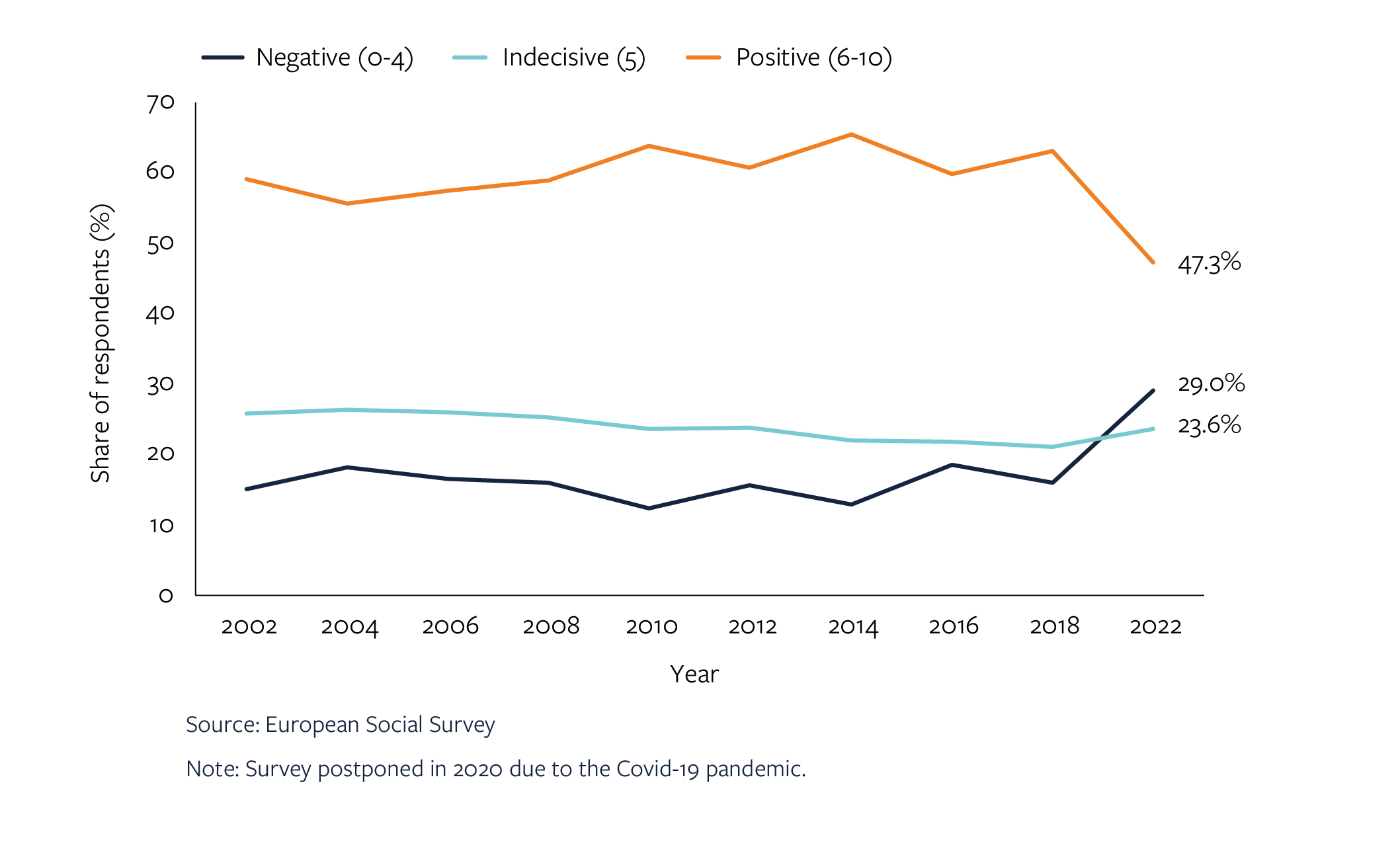

What is often surprising in this area is both the resilience – and positivity – of broader public attitudes towards immigration. We see this across Europe, where attitudes towards immigration have been increasingly positive over the long-term. Sweden and Denmark are no exceptions. Both countries – though particularly Sweden – have shown positive attitudes over the last two decades, when the public is asked ‘does immigration make your country a worse or better place to live.’

However, Sweden has taken a dramatic turn in recent years, as the newly released data from the 2022 European Social Survey shows (see figure below). Clearly the public mood on immigration has changed, possibly driven by discussions linking crime and immigrant background which were also a central feature of the recent Swedish elections.

Does immigration make Sweden a worse or a better place to live?

An alternative way forward

Sweden and Denmark are representative of a wider, highly concerning, trend spreading across Europe where more moderate parties form alliances with, and make concessions to, the far-right on immigration to stay in power. And while these responses may look like shrewd political strategies on the part of the centre-right and left-wing parties, there will surely be many asking the question: is there not a better way for politicians on the left to respond to the rise of the far-right?

These answers are far from the rational and pragmatic response that European countries require in light of current challenges. Like all European countries, Sweden and Denmark need immigration to fill major labour gaps. And both countries certainly have the resources to manage integration effectively, with Denmark registering some significant success in improving refugees’ labour market access in recent years.

Both Sweden and Denmark could better channel their energies towards maximising the many economic and social benefits of migration, alongside fulfilling their international responsibilities and legal obligations towards asylum seekers and refugees. The challenge remains to find the politicians and leaders who can offer more courageous political narratives that foster tolerance and social cohesion to support these efforts.

Related listening

This podcast dissects attitudes and approaches to immigration across Europe, highlighting how political narratives are often at odds with public opinion.