There is ever more need to move away from an unhelpful binary distinction between achieving development and addressing climate change. The effects of climate change, including actions to mitigate it, are reshaping development pathways on a global scale.

A global economy being reshaped by climate change

Much of the focus on climate and development has centred on the allocation of the marginal ‘aid’ dollar. This has been especially contentious in discussions around the reform of the World Bank, where a greater emphasis on more closely tying allocation decisions to reductions in carbon emissions could have significant distributional implications. It is understandable that, in the absence of increased resource commitments, conflicts between countries and different communities of activists and policy specialists are arising as a result.

There is a risk, however, that debates over resource allocation and related trade-offs obscure a deeper interrogation of how climate change and our response to it could profoundly reshape economic development pathways. The physical effects of climate change are of course well known and becoming increasingly visible in all parts of the world. However, less attention has been paid to how efforts by the world’s large powers to decarbonise their economies can affect development pathways. These efforts affect flows of finance, goods and services, investments, technologies, skills and labour. Governments and firms are under pressure to invest to adapt to a changing global climate, but also a global economy being reshaped by climate change.

A glass half-full or half-empty?

Governments around the world are positioning the green transformation and green industrialisation as an opportunity to transform and revitalise economies, just as the Biden administration has done through its Inflation Reduction Act. The Indonesian government is promoting foreign investment in domestic nickel refining, adding value to its nickel ore reserves, which play a globally significant role in electric vehicle batteries. The new Brazilian government is looking at how preservation of the Amazon can be used to command wider investment in the economy.

Similarly, at this week’s African Climate Summit, African leaders will highlight how they can be a major part of the climate change solution, as a green cost-competitive hub for the production of the required inputs. This is in view of Africa’s supply of critical minerals and renewable energy potential, the opportunity for value addition in certain sectors, and more broadly, technology sharing to reduce emissions.

A more pessimistic view suggests that the policy measures being taken by major global players are the latest efforts to ‘kick away the ladder’ of development: essentially a green-tinted wave of protectionism. The costs of entering markets are increasing due to new green compliance requirements, which can exclude smaller, poorer producers unless support for adjustment is provided. Carbon border adjustment measures are being implemented now by the European Union, but there remains a lack of clarity regarding the support to be provided for adjustment, especially for Least Developed Countries. There remain unfulfilled promises of technology transfer. Similarly, despite some building momentum, responses to the demands for low-cost, long-term finance to support green transitions remain lacklustre.

Whether the spectre of climate change contributes to economic boom or bust will likely vary across economies. Some of that variation will be down to the actions of national and sub-national policymakers. There is a clear trend internationally to use more activist policies to secure benefits from decarbonisation efforts, but industrial policies can be done well or badly. Banning exports of raw minerals by no means guarantees a vibrant processing industry.

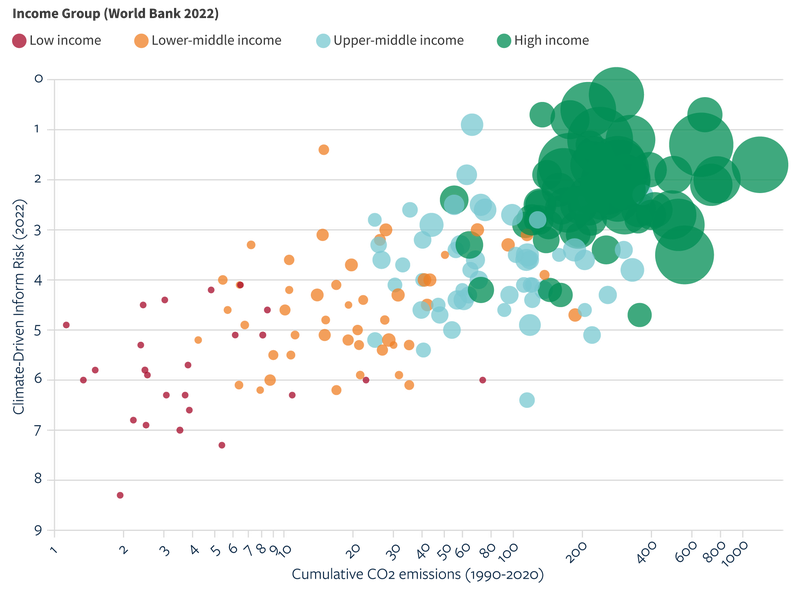

Many countries most at risk from the direct impacts of climate change are less well positioned to take advantage of economic opportunities, with fewer resources to invest and fewer pre-existing assets to draw on; they are also typically the same countries that bear the least responsibility for climate change. Moreover, high vulnerabilities to environmental shocks means confronting the climate emergency with already constrained fiscal positions, with levels of indebtedness increased by past climatic events.

Figure 1: Country CO2 emissions per capita, climate-driven risk and GNI per capita

Source: X-axis (log scale): World Bank, 2023a. Y-axis: IMF, 2023. Bubble size (GNI per capita, Atlas method, current USD): World Bank, 2023b/latest available estimate. Bubble colour (World Bank income group classification): World Bank, 2022

The countries that have the most power to shape future global carbon emissions and the decarbonisation efforts shaping the global economy have a dominant role in the multilateral system. To date, more progress has been made in deterring investment in ‘climate bads’ (e.g. limiting access to international finance for fossil fuel investments) than in facilitating greater investment in cleaner alternatives (e.g. expanding the financial headroom of the MDBs). Trade measures tying climate action to economic (and security) ambitions have been adopted, and promoting the re-shoring of previously offshored activities. However, the process of ‘friend-shoring’ remains opaque. Although there is rising demand for certain skills like retro-fitting, there is limited use of migration policy to help meet related workforce challenges.

Looking ahead

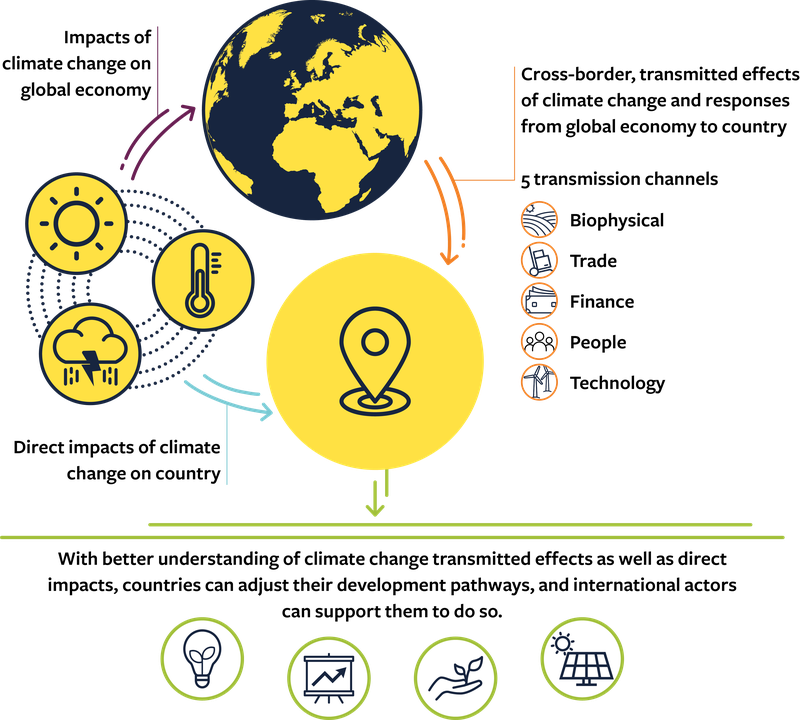

At ODI, we have published a briefing paper that draws attention to the cross-border effects of climate change, which arise from direct physical impacts and adaptation efforts but also the actions taken to decarbonise the global economy. It does not pretend to offer a solution on how countries can secure development in a climate-changed world. It does however highlight how the transmitted effects of climate change and its response are being systematically overlooked.

The report highlights how greater focus is needed on the supply-side response to the transmitted effects of the global climate response, moving beyond a narrow focus on finance to encompass many other domains including trade, innovation, natural resource management and migration. This requires consideration of the kinds of institutional capabilities required to navigate such spill-overs and the appropriate international economic statecraft.

Most importantly, it draws attention to the incongruity of consistently pushing national-level reforms to solve global problems. It is undeniably absurd when low- and middle-income countries are being asked to implement 30 or more policy reforms to access concessional finance, especially when the roots of their challenges are international in nature. As the Africa Climate Summit gets underway, Kenya’s President Ruto rightly emphasises the urgent need for the Global North to provide greater policy space for the Global South to take effective action.

Figure 2: A framework for assessing the transmitted effects of climate change

Source: Authors