Migration management remains high on political agendas across Europe, after Frontex figures showed 330,000 irregular border crossings in 2022 (an increase of 64% over 2021). The numbers of crossings (not to be confused with the numbers of people arriving) are far from unprecedented (for example, compared to over 500,000 irregular crossings in 2016). However, many member states are calling for action. A recent European Council summit committed to ‘using all relevant EU policies and instruments including diplomacy, development, trade and visas, and legal migration’, particularly to induce countries of origin to cooperate on the EU’s returns policy.

This is certainly not new. The EU has long experimented with programmes that incentivise accepting returnee migrants. Trust Fund programmes which are posited to address the root causes of irregular migration have also become common. The EU Emergency Trust Fund for Africa (EUTF) received 5 billion euros in pledges between 2015 and 2020, including 4.4 billion euros from the European Development Fund. Since 2021, migration and border management have been included in the EU’s Multiannual Financial Framework, consolidating its financing within the bloc’s annual budget.

Concerns around combining migration management with development policy

Concerns in this area are well established. In particular, there is significant academic literature looking at the EUTF that finds negative implications for migrants and citizens alike, including that funding has empowered security actors and risks increasing repression and rights violations.

It has also diverted aid priorities – as illustrated by Niger's experience, when funding targeted migratory routes and migrants rather than national development priorities. As ODI's own research on Niger has shown, efforts in the region to criminalise irregular migration disrupt traditional migration routes, introducing significant hazards to journeys and negatively impacting livelihoods strategies.

There are also valid concerns – explored by the European Policy Centre – about the tensions between negative conditionalities and the strategic cooperation sought under the EU’s Talent Partnerships. Conditionality around irregular migration and return complicates the buy-in required from third countries and jeopardises private sector collaboration. Who will invest in labour mobility schemes if these could be suspended as punishment for failures around migration control?

Perhaps most notable are the ongoing controversies around the EU’s training and funding of the Libyan coast guard, which intercepts refugees and migrants in the Mediterranean sea and returns them to detention in Libya. A comprehensive new report by UN Human Rights experts documents numerous cases of murder, rape and enslavement, as well as systematic torture and ill-treatment of migrants in official detention centres in Libya.

How migration management is being supported by the EU remains a very live issue of concern.

The flawed assumptions underlying the EU’s approach

Addressing the root causes of migration remains the fundamental tenet of the EU’s approach. A core belief which underpins the EU’s strategy and funding is that promoting economic development will reduce migration.

But research shows that migration does not arise because of failed economic development – rather, extreme poverty tends to immobilise people. A wealth of evidence from the last half century points to the fact that migration is driven by economic development.

What is also well established – including through ODI's own research – is that migration can have highly developmental impacts. Remittances are a powerful poverty reduction instrument and international labour migration can reduce poverty for migrants themselves, their families and in host and origin countries. Developmental benefits are maximised when migration is safe and orderly, and when regular pathways are provided.

The new plan

Nothing cited here is a revelatory finding. However, despite this evidence – and the longstanding concerns about tying development aid to migration management – many European actors are doubling down on this approach.

The Netherlands has been vocal in its support for using all available policy tools to deter irregular migration and Sweden has emphasised the importance of achieving increasing returns of failed asylum seekers during their presidency of the EU Council.

The focus on increasing returns

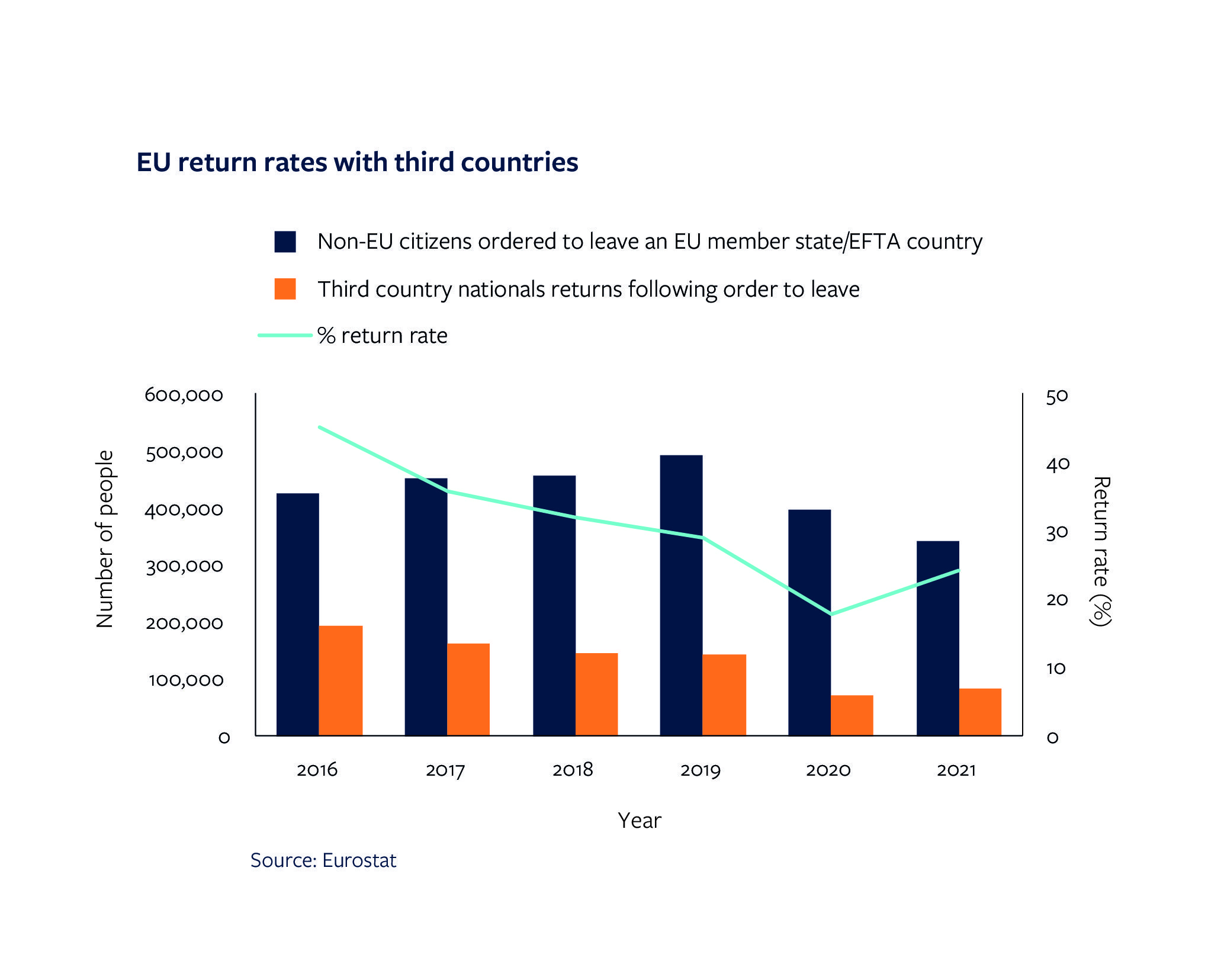

The lack of progress with the return and readmission of migrants has been an ongoing source of dissatisfaction for the EU. Return rates are generally low, with the average EU rate dropping significantly since 2016. By 2021, only 24% of people who were asked to leave EU countries were actually returned to third countries.

While this may look like a problem that can be solved by conditionalities around trade, aid and visas, that may be a simplistic reading. Research has demonstrated just how little formal and informal agreements, and cooperation, actually matter for determining changes in return rates with third countries.

This is a complex area. There are all kinds of reasons why states find it difficult to enforce returns, including the growth in anti-deportation campaigns, as well as because existing international human rights standards make it difficult to return migrants to certain countries. It may well be conceptually flawed to allow return rates to influence these discussions at all.

The impact of withdrawing trade preferences under the GSP

Given there are serious debates about this, it is worth reflecting on the nature of the threat of withdrawal of access to the EU’s Generalised System of Preferences (GSP) as is currently being discussed.

From certain vantage points such a threat may look fairly empty. Many African countries are simply outside the frame of discussion. For example, Tunisia and Morocco – heavily implicated in migration management debates – have access to EU markets on the basis of their own trade agreements. Many countries in West, East, Central and Southern Africa also trade under the EU's Economic Partnership Agreements. As formal trade agreements – in contrast to the unilaterally bestowed benefit of the GSP – the possibility of suspending these is not straightforward and would most likely imply violating international law.

However, for a smaller number of countries – and specific export sectors – the threat of withdrawing preferential access to EU markets is significant. Countries such as Bangladesh and Pakistan rely strongly on the GSP for their textile and garments exports. They benefit from duty free and quota free access to the EU for these exports under the Everything But Arms initiative and the Special incentive for Sustainable Development and Good Governance (i.e. GSP+), respectively. And both countries figure prominently in the EU's list of nationalities ordered to leave.

In the case of Bangladesh, losing its GSP status would be significant. Clothing exports make up over 90% of the country's exports and 60% of exported garments go to EU markets. The industry is a major contributor to the country’s manufacturing base, the centrepiece of the country's economic success story and a huge employer of almost 4 million people (who are predominantly low-paid women workers). Any loss of export sales would have serious ramifications, including likely industry relocation and job losses, with major developmental impacts.

Some are questioning whether such a move would even be compatible with WTO rules, which are specifically designed to guard against political interests and conditionalities coming into play.

There are also many stakeholders in the EU who could be affected. Applying such conditionalities would have significant implications for European multinationals who have invested over decades in developing garment supply chains in Bangladesh and Pakistan.

The EU must rethink its objectives

Ultimately the EU is faced with a bigger question: is the fundamental goal of development aid and policy to curb irregular migration or to reduce poverty? Any desire to orient programming to “address the root causes of irregular migration” rests upon an outdated frame, one not backed up by evidence and inconsistent with the reality of forced irregularity experienced by many migrants. Negative conditionalities around trade could do significant damage and the legal and financial risks – for multiple stakeholders – appear significant.

This is an area that merits careful diplomacy and, ideally, a partnership of equals seeking to solve shared challenges, alongside generous development aid and expanded legal pathways for labour migration. A well-functioning international protection system remains a basic ingredient, though one unfortunately side-lined as a priority in current debates.