There is broad-based consensus that gender-based violence (GBV) escalates during humanitarian emergencies. For displaced people, opportunistic GBV along the migratory route and in settings such as camps and settlements is the most visible and readily acknowledged form. But HPG’s recent research on gendered norms and roles shows that crises also have an impact on domestic and intimate-partner violence and other forms. In fact, GBV is so prevalent that the current Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC) guidelines call for humanitarians to assume it is always present in crisis settings – even without evidence – and act accordingly.

GBV is rooted in social norms

When crises strike, we often turn to sociocultural explanations for rising GBV – that is, to the heightened vulnerability that comes with fleeing home, temporary housing and the breakdown of social networks. Amongst very conservative Muslim communities, displacement by conflict or natural hazards may be the first time in their lives that women live in close proximity to men who are not their relatives.

In Pakistan’s Punjab province, we recently wrote with GLOW Consultants about how restrictive notions of ‘honour’ – or izzat in Urdu – were impeding women from seeking safety in the wake of recent flooding. Add to these social constraints, the high risk of sexual violence in a region that offers little redress for survivors, and the likelihood of being blamed and stigmatised for perceived damage to their ‘honour’, women and girls are left in a very precarious situation: flee – with all the risks it entails – or stay behind and face the hazards of flooding or armed groups.

It bears noting, of course, that such codes are the product of patriarchal social norms rather than a reflection of Islamic doctrine – indeed, HPG research has shown that Islamic education, especially for women and girls, creates an alternative source of knowledge to strict honour codes and thus a rival source of authority. As one young woman highlighted: ‘Islam teaches us to fight for your own rights and that is why the girls who are enrolled in madrassa are now aware of their own rights.’

But climate also plays a role

While these sociocultural explanations for GBV are widely accepted, less emphasis is placed on climatic factors. Climate-related risks tend to be interpreted as natural and inevitable events and the outcome of the ‘uncontrollable’, ‘unstoppable’ force of climate change, rather than of wider social inequality and proactive political will. But the unequal experience of women and girls highlights that there is nothing inevitable or natural about the structural violence of the cyclone.

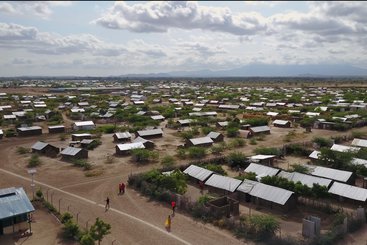

Our research in northern Mozambique illustrates these dynamics. In 2019, Cyclone Kenneth (the strongest cyclone on record ever to hit the African continent) struck northern Mozambique, inflicting widespread damage and destruction to houses, infrastructure and livelihoods. In the words of one of our respondents: ‘The cyclone damaged everything – from farms to houses. There are no fish in the sea. Everything is destroyed. Nothing remains.’

But the impacts of the cyclone were not felt equally. Women and girls were more likely to die and be displaced, and to lose access to health and education services as a result of Cyclone Kenneth. This vulnerability was brought into focus by one internally displaced person (IDP), a woman struggling to feed her children on her own, and with no support from her wider family: ‘if I’m lucky, a man will look at me and say they want me for 100 meticais [$1.50]’ – money that she subsequently used to buy basic food and water supplies, and without which the survival of her family would be compromised.

The violent impacts of climate events are further accentuated when climate change combines with conflict to create compounding risks and vulnerabilities. In addition to regular cyclones, floods and unreliable rainfall, a violent insurgency characterised by abductions, beheadings, burnings, beatings, kidnappings and sexual abuse has displaced nearly 1 million people in northern Mozambique since 2017. These compounding risks were recognised by an IDP woman: ‘Our houses were destroyed by the rain, and what was left of them was destroyed by the war.’

Women are structurally vulnerable to climate hazards

Unequal impacts are the outcome of systematic political disadvantage, economic marginalisation and disproportionate exposure to hazards experienced by women in northern Mozambique – all of which limit their resilience and capacity to adapt, even normalising the harms faced by women and girls as inevitable collateral damage. Climate change thus adds an additional layer of risk for already vulnerable women and girls around the world, playing an important but little-acknowledged role in shaping their prospects for wellbeing and agency.

Many countries have codified their commitment to global women’s rights by signing on to the Women, Peace and Security agenda, or by adopting a ‘feminist’ stance in their foreign policies. Many of those same countries are amongst the biggest contributors to climate change. Much like armed conflict, climate change is neither ‘natural’ nor free from gendered impacts.

Considering all of this, and with COP27 still fresh in our minds, it is time to think differently about climate change as a driver of GBV around the world, particularly where it intersects with conflict in complex crises. Real feminism means real action on climate change.