Record-breaking monsoon rainfall between June and August 2022 resulted in unprecedented flooding across Pakistan, causing widespread loss and damage. With around one-third of the country under water and a widespread loss of homes, crops and livestock, 6 million people are now in need of urgent help.

Encircled by rising floodwaters, the remote community of Basti Ahmad Din in Punjab Province has become an island, cut off from its neighbours and only accessible by boat. Despite chronic shortages of food and supplies and the spread of waterborne disease, only the men were permitted by community elders to travel to the nearest relief camp for aid and supplies.

The women of Basti Ahmad Din stayed put. Not because they were physically unable to move, but because their leaders were unwilling to risk compromising their honour. A strict honour system prohibits women in conservative communities in Pakistan from mixing with men outside of their families. Moving to higher ground would compromise this, as it entails leaving the seclusion of home, passing through public spaces and resorting to emergency shelter often shared with strangers.

Our conversations with humanitarian workers reveal that Basti Ahmad Din isn’t an isolated story. In Rajanpur district in Punjab Province, similar concerns about women leaving their homes led to delays in seeking safety that contributed to the deaths of dozens of people, mainly women and children. Similarly, in Sindh Province, women and children from Sarfaraz Punjabi village (located on the banks of the Indus River) and the coastal village of Ali Muhammad Jutt reportedly stayed behind in areas at risk of flooding, while men moved to safer ground elsewhere, often with livestock.

Similar dynamics are documented in Bangladesh. When cyclones strike, women, children and the elderly are often the last to evacuate, if they leave at all. The reasons for this are complex, and brought about by social and cultural expectations rather than by innate or natural differences between the sexes. For example, women not knowing how to swim, wearing clothing that restricts mobility, greater responsibility for childcare that limits options, and fear of sexual and physical abuse should they move.

These experiences illustrate the gendered immobility of displacement and the importance of early-warning systems that can help women reach safety. Women’s (im)mobility and honour are closely linked in conservative and patriarchal communities in Pakistan. They are often not free to move to the same extent as men, even when their life (and the lives of their children) depend on it.

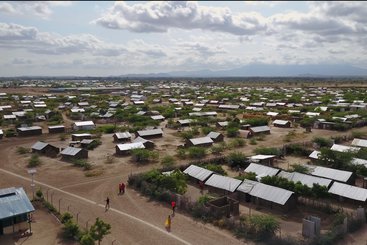

In addition to socially and culturally constructed norms about what is appropriate, the very real risks to women of displacement – routine discrimination and violence – function as another barrier to moving. Communities have legitimate reasons to be worried about the safety and dignity of women and girls in internally displaced person (IDP) camps in Pakistan. Insecure, over-crowded and poorly lit shelter and sanitation facilities lack in privacy and leave women at real risk of sexual abuse and violence.

Alarmist headlines of mass migration and displacement linked to climate change have become commonplace. These overlook those trapped by financial barriers or by the constraints posed by conflicts, hazards and politics. Even less is known about those who choose (or for whom the choice is made by others) to stay behind for cultural reasons. A key reason for this blind spot is that displacement is typically understood through a migration lens: to be displaced is to be forced to move elsewhere. And yet, as the anthropologist Stephen Lubkemann argues, this starting point ‘renders invisible an entire category of people who suffer a form of “displacement in place”’.

The women of Basti Ahmad Din are similarly displaced in place. While they themselves haven’t physically moved, the world around them is changed and almost unrecognisable, with farmland, buildings and roads now underwater. And, trapped in a community cut off from assistance, their experiences of hardship and suffering echo those endured by IDPs who have had to move elsewhere.

As the scale and intensity of climate change becomes increasingly apparent, more attention must be paid to the nuanced and gendered experiences of women and children who are often most at risk, but least able to move.

Pakistan could look to the gains made in Bangladesh, where the number of disaster-related deaths has fallen sharply. Improved early-warnings systems have played a key role. But so too have community-managed shelters, which decrease the risk of gender-based violence. And the 'army' of female volunteers proactively working to change community attitudes and increase knowledge about risks and evacuation so that women don’t get left behind when disasters strike.