With the Russian invasion of Ukraine now in its second year, the question of how – and when – the conflict might be brought to a close is becoming increasingly urgent.

The prospects for a negotiated settlement are admittedly not encouraging, at least in the near future. Key leaders in the West, and the Ukrainian themselves, are clear that only a decisive military conclusion in Ukraine’s favour will be sufficient, both to restore Ukraine’s internationally recognised borders and to rebuff any broader strategic ambitions Russia may have in its vicinity.

President Joe Biden’s recent visit to Kyiv was a potent demonstration of presidential resolve. UK Prime Minister Rishi Sunak has announced that his government would be ‘doubling down’ on its military support. There is an overwhelming Western consensus that the only acceptable answer to Russian aggression is for Ukraine to win. In his joint press conference with Biden, President Zelensky restated that only the expulsion of Russian forces from the entirety of Ukraine’s sovereign territory, and security guarantees against future Russian aggression, would bring satisfaction. President Putin is not backing down either, as his state of the nation address at the end of February grimly underlined. Putin shows not the slightest sign that he envisages any outcome short of military victory.

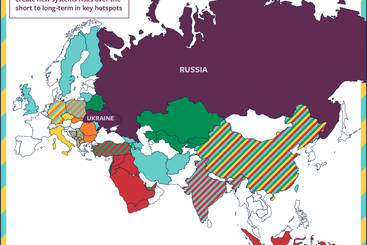

Both sides are committed, at least publicly, to resolving the issue on the battlefield. Other assessments suggest, however, that, without a substantial escalation in outside support, a decisive military outcome will not be achieved. More likely is a long, attritional and inconclusive struggle, the effect of which could be to add Ukraine to the list of ‘frozen conflicts’ already littering the post-Soviet space.

Given this bleak prospect, are there avenues which might promote a peaceful resolution through diplomacy and negotiation?

There are strong political and strategic arguments against seeking a negotiated solution, at least until the battlefield calculus has shifted definitively in Ukraine’s favour. Any proposal at this stage in the direction of negotiations risks weakening the Western coalition in support of Ukraine and emboldening Moscow. Ukraine has an absolute right to independence, and the right to resist an illegal and brutal invasion which is designed to remove that independence. There is, and can be, no ambivalence about how this conflict came about: Russia is the aggressor and Ukraine the victim.

At the same time, the human suffering and physical destruction the war has brought about, and the prospect of further devastation should it continue indefinitely, compel consideration of whether there may be opportunities to lay the basis for a peacefully negotiated outcome – an outcome which would not reward aggression or betray the Ukrainian people’s heroic resistance and self-defence, but would find a workable way forward based on the peaceful resolution of differences and respect for territorial sovereignty and integrity.

A year into the conflict, we need to start exploring options for making progress through diplomacy and mediation. There has been speculation that Beijing might be ready to offer itself as a broker for peace. Other countries, or groups of countries, could potentially play a role as bridge-builders. Multilateral frameworks could also help facilitate discreet contacts. Even if the current outlook is not promising, we should consider whether there are small steps that could be taken to build trust and lay the foundation for dialogue and negotiation.

There are, unfortunately, no ready-made roadmaps or blueprints here. Past peace settlements, for instance those in Sudan and the Balkans or the Northern Ireland peace accord, do not offer much beyond general guiding principles. The lessons of history, moreover, suggest that conflicts tend to end only when either defeat or exhaustion forces enemies to look for peace. But acknowledging that settlements are difficult and complex should not preclude efforts to find ways to talk and to develop channels for contact and engagement.

This is not an argument for some Dayton-style framework, for a version of the Good Friday Agreement or for another Juba Accords. The time for that is not now, if it ever comes at all. But betting everything on a belief that somehow sending tanks, bombs and bullets will be enough, while neglecting to at least think through other, non-military options, risks condemning Ukraine and its people to perhaps years of war, suffering and displacement. The scars of that will take generations to heal.