The poorest people in the world should not be deprived of development in the name of decarbonisation. This is by no means a new argument, but one that remains sidelined at international discussions, including the recently concluded COP28.

Our recent report, “Improving living standards within stringent carbon budgets: the critical importance of climate equity”, examines the intersection of three global priorities: rapid reduction of poverty, inequality and emissions. Recognising that the climate, poverty, and inequality crises are intertwined, the new findings in this paper—summarised below— support longstanding calls for a more equitable way forward.

Inequality within countries has become an increasingly important driver of emission inequality

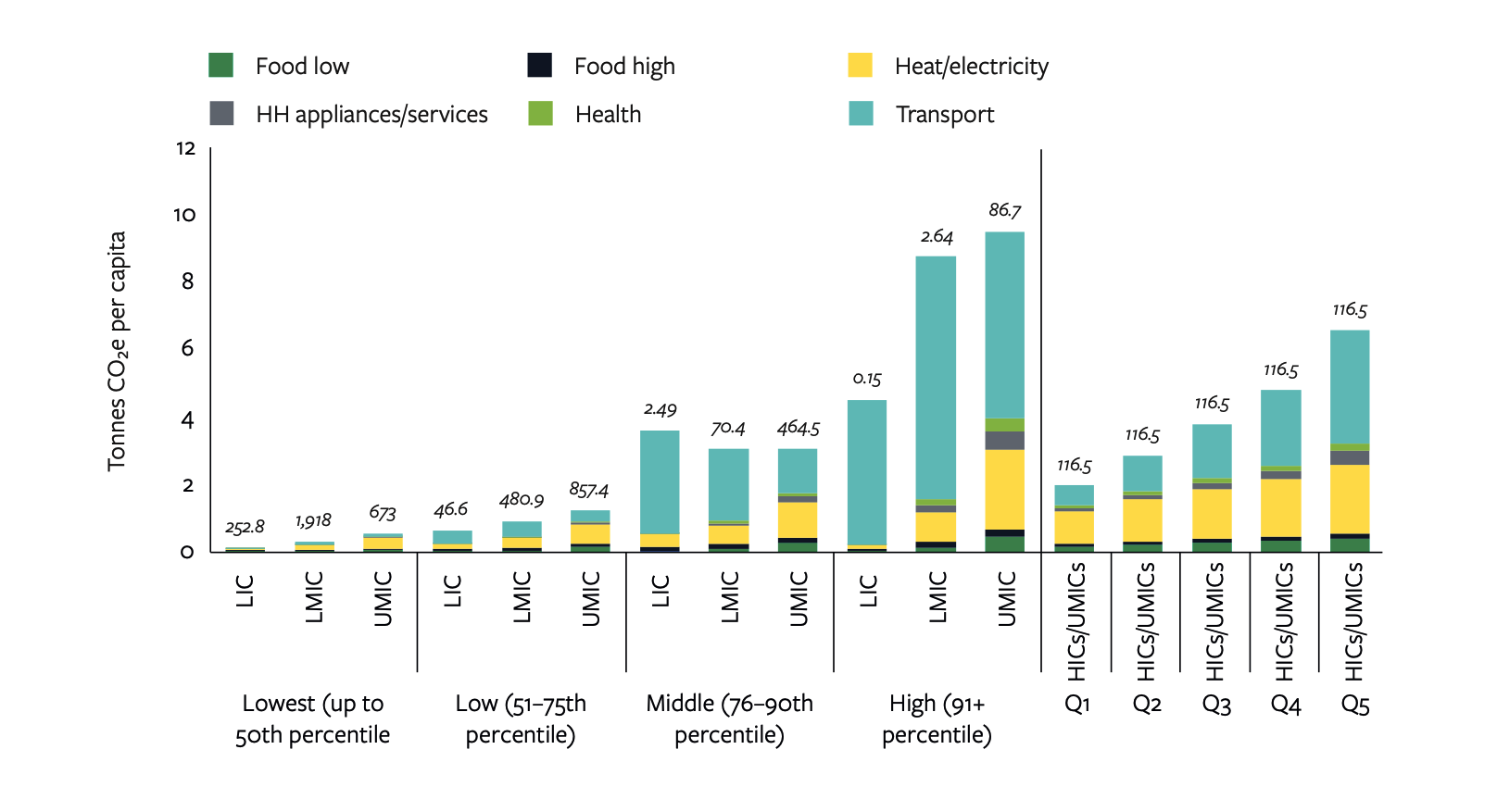

Over the past 30 years, inequality within countries has become an increasingly important driver of emission inequality, with carbon footprints closely linked to income and consumption. These inequalities can be severe. By 2019, 64% of carbon inequality was due to inequality of emissions between income groups within countries. What this means is that the wealthiest individuals in countries like India or Nigeria, for instance, may emit as much as Germans.

At the same time, our findings underscore that most Indians or Nigerians have very small carbon footprints, unlike the average or even poorer Germans. The population sizes of different consumption segments in Figure 1 illustrates this case.

Moreover, the bottom three-quarters of the global consumption distribution based in low- and middle-income countries outside Europe have considerably lower per capita expenditures, on average, than their counterparts in European upper-middle-income countries and high-income countries. This difference would be even starker if we consider other Western nations (e.g. United States, Canada or Australia) or other high-income countries (e.g. those in the Persian Gulf).

The continued deprivation of people in poverty won’t save the planet from climate change

Additionally, even if we raise the living standards of billions of people who currently consume too little for their own well-being, their per capita emissions would still be very low and their aggregate emissions quite modest. In other words, continuing to deprive people in poverty will not save the planet from climate change.

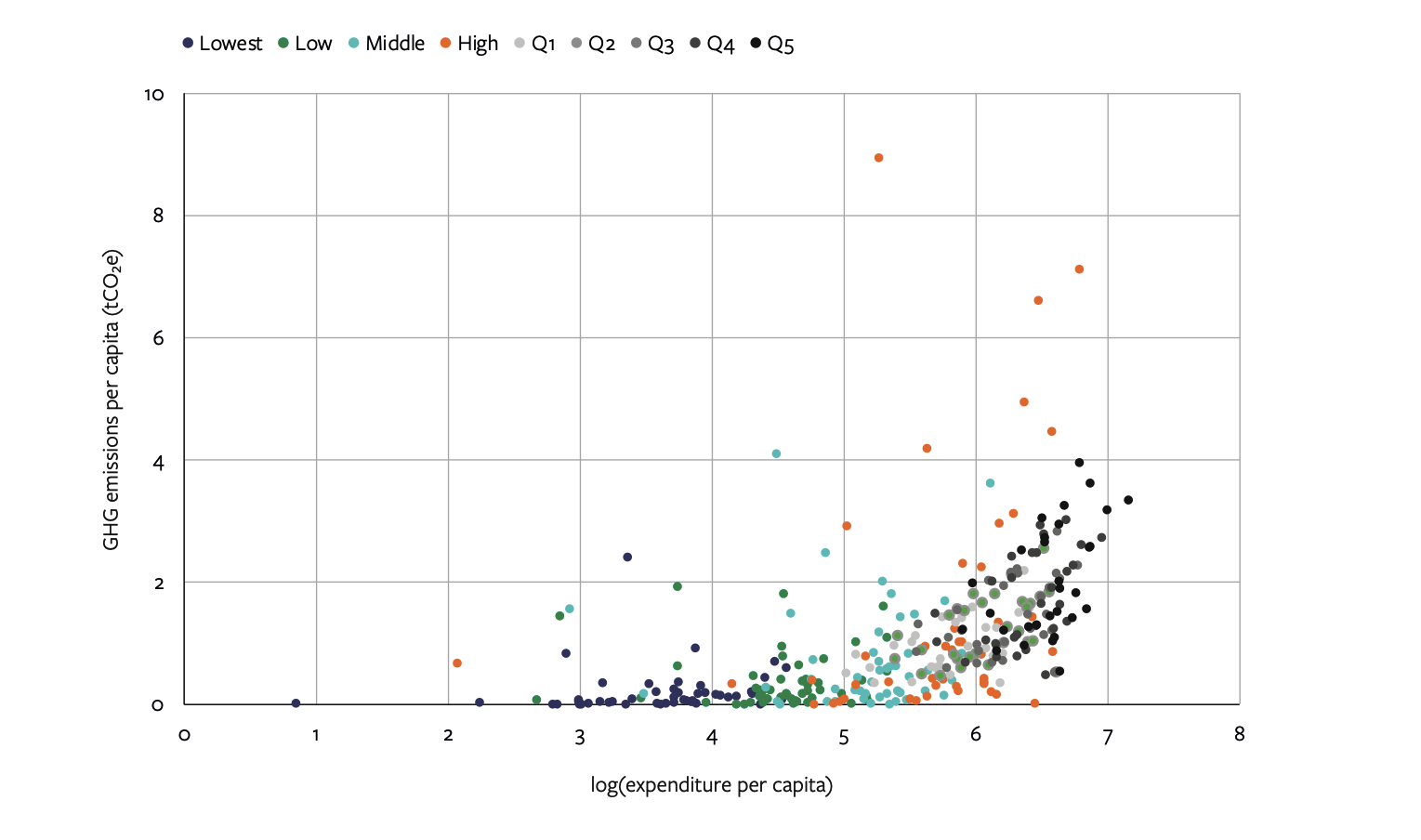

The good news for countries at all levels of economic development is that there is not necessarily a stark choice between improving living standards and avoiding greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. The very large differences in per capita emissions of high- and upper-middle-income countries (see Figure 2 for the heating/ electricity sector) demonstrates how societal and historical choices regarding infrastructure, urban form, and individual behaviour can lead to dramatically different levels of per capita emissions. Therefore, it is very much possible to achieve high living standards without high emissions.

Achieving high and more equitable living standards without high emissions

Increasing the living standards of people in and near poverty can also be supported by reducing consumption by the global rich. The challenge in this will be breaking away from path dependencies, behaviours and economic structures to facilitate individuals to choose lower emission livelihoods without lowering their well-being.

Additionally, there are low-carbon options available for reliable power, access to goods and services, and nutrition that can be considered. The relative affordability and viability of these options are shaped partially by exogenous factors such as technological costs, established infrastructure stock and availability of land, but also by endogenous factors such as regulatory environments, planning decisions, acquired capabilities and cultural norms.

To make this a reality, upper-middle and high-income countries need to raise the ambition of their Nationally Determined Contributions in line with their “fair share” of effort. The specific policies and investments required to achieve these goals will vary from country to country but may include reforming energy and agricultural subsidy regimes that favour unsustainable production and consumption, establishing integrated spatial and infrastructure investment plans that can underpin a pipeline of climate-safe, bankable projects in the transport sector, and reforming national dietary guidelines and – where applicable – procurement policies to favour plant-based diets.

At the same time, there needs to be a renewed global effort to improve the living standards for the poorest 50% of the global population, who mostly live in low- and lower-middle-income countries. People living on less than $2.97 a day frequently lack access to adequate, nutritious food, reliable, modern energy, adequate healthcare services, and the other fundamentals for a decent quality of life.

To support this equitable development, higher-income countries need to provide more generous and integrated support for climate-compatible development in lower-income countries. The climate accords outline the need for developed countries to provide climate finance, technology transfer and capacity building to enable low- and middle-income countries to mitigate and adapt to climate change. However, such support has fallen woefully short of the needs of low- and middle-income countries.

By prioritising equity, we can ensure that there is atmospheric space to make high and equitable living standards a reality for all.