Around the world, a fiscal squeeze is under way. Many governments are reducing spending, others are trying to increase their revenues, and some are doing both. The need to reduce fiscal deficits due to the rising cost of debt is the common driver across countries.

But how governments have accumulated this debt varies, as does their room for manoeuvre. The fiscal squeeze is particularly notable in sub-Saharan Africa, and short-term pressures may crowd out longer-term concerns unless the international community acts.

Back in October 2019, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) was expecting a mild recovery in global growth over the period 2020 to 2024. The Covid-19 pandemic shattered these economic forecasts. Faced with the need to provide unprecedented levels of support to households and businesses during lockdowns, governments were forced to borrow to keep their economies afloat. Public finances were further hit when Russia’s invasion of Ukraine pushed up fuel and fertiliser prices, exacerbating rising inflation around the world. When the US Federal Reserve responded with the fastest interest rate tightening cycle for four decades, lower-income countries experienced exchange rate depreciations against the US dollar that increased their debt burdens and debt servicing costs.

Figure 1: Global growth forecasts were upended by the Covid-19 pandemic and the Russian invasion of Ukraine

This blog post explores how IMF forecasts have changed between the October 2019 and the April 2023 WEOs, and what that means for government finances.

Public finances under pressure

The unprecedented scale of the fiscal response to the pandemic was uneven across countries (see Figure 2 below). With some exceptions, the response was significantly larger in advanced economies than in emerging markets and low-income countries. While government support in the form of extra spending or revenue cuts was in excess of 10% of 2020 GDP in advanced economies (and as high as 19% and 25% of GDP in the UK and the US respectively), only a handful of African countries spent between 5-7.5% of 2020 GDP, and most spent less than 2%.

Figure 2: Additional spending or foregone revenues in response to the Covid-19 crisis as of September 2021, % of 2020 GDP

The war in Ukraine compounded the price pressures created by Covid-19 bottlenecks and pushed inflation levels far higher than expected. While government efforts to address the cost-of-living crisis further strained public finances, central banks responded by raising interest rates, thus increasing the cost of debt servicing. This was particularly felt by emerging and low-income economies which experienced currency depreciations and held dollar-denominated debts. Thanks to excessive borrowing, several countries already had elevated debt-to-GDP ratios prior to the pandemic (such as those in debt distress in Southern Africa), and therefore had little fiscal space to respond to these crises.

Figure 3: The debt-to-GDP ratio has ballooned since the Covid-19 crisis and remains high in several regions

As a result, the debt burden jumped up in many parts of the world. Debt-to-GDP ratios in advanced economies, emerging and developing Europe and sub-Saharan Africa are ten percentage points higher today than forecasted by the IMF in 2019 (see Figure 3 above). Meanwhile, net interest payments are increasing in many regions, which means other parts of spending and revenue will have to be squeezed further to restore public finances to a sustainable level.

Figure 4: Net interest payments are rising in most regions, adding pressure to public finances

Reducing fiscal deficits and debt burdens are projected to be major themes for many countries in the future, which explains why we have entered a period of widespread fiscal squeeze.

Do fiscal squeezes work?

Fiscal consolidations – the technical term for austerity (or a ‘fiscal squeeze’) – come in many shapes and forms. Alesina et al (2019) differentiate between spending reductions and revenue increases, while Hood and Himaz (2017) go further by additionally distinguishing real-term changes from changes as a share of GDP.

Another consideration is how much of a fiscal effort qualifies as a fiscal consolidation: for instance, Ardanaz et al (2021) set a 1.5% of GDP improvement to the fiscal balance as a threshold (adjusted to remove cyclical revenue and spending, e.g. automatic stabilisers such as unemployment benefits), or a two-year consecutive improvement of at least 1.25% of GDP. Hood and Himaz (2017) require an increase (fall) in revenue (expenditure) of 1% of GDP, and of 1% in real terms.

These methodological debates matter, since they can yield different policy recommendations. Alesina et al (2019) argue that reductions in expenditure are less contractionary than increases in revenue, while Guajardo et al (2011) find the opposite. Meanwhile, Arizala et al (2017) and Ardanaz et al (2021) state that cuts to public investment are particularly harmful compared to cuts to public consumption.

Context also matters. Following the 2007-08 financial crisis, excessive austerity was blamed for delaying the economic recovery (Blanchard and Leigh, 2013). However, the aftermath of the crisis was characterised by very low inflation and interest rates effectively at the zero lower bound, increasing the effectiveness of the fiscal multiplier (IMF, 2014). Although the current context of high inflation and interest rates is more favourable to fiscal consolidation, there are still risks. In low-income countries, expenditure cuts may rapidly affect essential public services and there may be considerable pressure for public wages to keep up with inflation.

Balasundharam et al (2023) and IMF (2023) list other factors affecting the impact of fiscal consolidations, such as the quality of fiscal institutions, the amount of political support, or whether consolidation is done outside a recession. Overall, Balasundharam et al (2023) found that between one-fifth and two-thirds of fiscal consolidations were successful (depending on the criteria used), compared to around half of fiscal consolidations in the IMF’s April 2023 WEO.

Breaking down the current fiscal squeeze

Fiscal balances deteriorated sharply in 2020 as a result of the pandemic response and have been slowly adjusting back to previous levels since – a multi-year process of fiscal consolidation that falls well within the standard definitions (Ardanaz et al, 2021; Hood and Himaz, 2017) of a 1 to 1.5% of GDP improvement in the fiscal balance, increase in revenue or fall in expenditure (see Figure 5 below). In sub-Saharan Africa, fiscal consolidation is forecast to be concentrated in 2023 and 2024.

Figure 5: Fiscal consolidation is under way in most regions, but has only just begun in sub-Saharan Africa

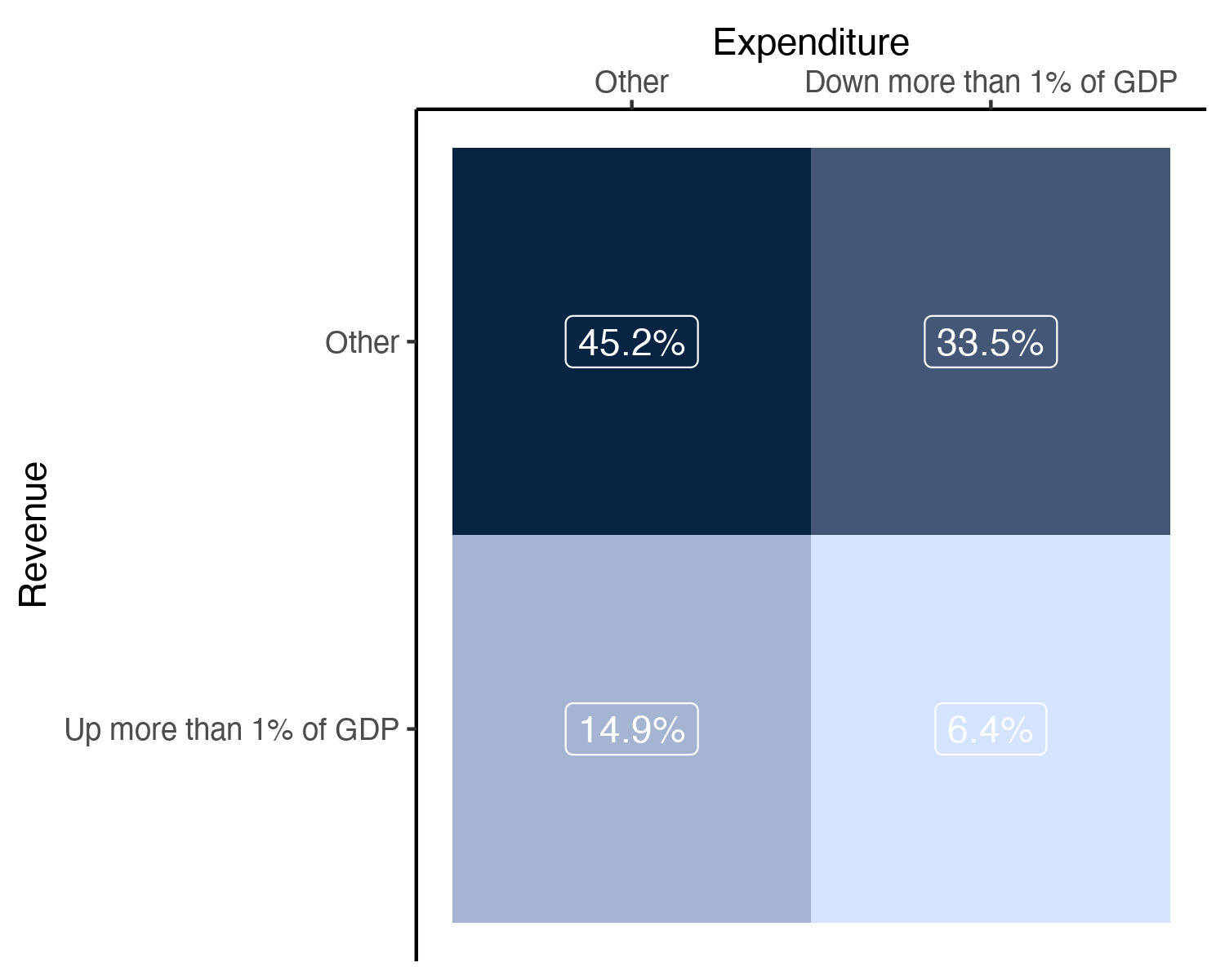

More than half (55%) of countries are forecast to engage in fiscal consolidation between 2022 and 2024 – defined here as a reduction of expenditure or an increase in revenue of more than 1% of GDP between 2022 and 2024 (see Figure 6 below). Expenditure reduction is the dominant fiscal consolidation strategy, with 33% of countries forecast to reduce expenditure by more than 1% of GDP and 15% of countries forecast to increase revenue by more than 1% of GDP. Approximately 6.4% of countries were expected to simultaneously increase revenue and reduce expenditure by more than 1% of GDP.

Figure 6: Expenditure reductions dominate revenue increases as a fiscal consolidation strategy

The focus on expenditure reduction is unsurprising given that, for most countries and regions, the fiscal consolidation we are seeing is related to the unwinding of expenditures related to the pandemic response (see Figure 7 below). However, there is a major difference in sub-Saharan Africa, which is the only region where expenditure is forecast to fall below their pre-pandemic levels. This fiscal consolidation is potentially much more painful.

Figure 7: The unwinding of Covid-related fiscal expenditure is the main driver of fiscal consolidation, except in sub-Saharan Africa

While all IMF country groups apart from the Middle East and Central Asia are, on average, forecast to cut back expenditure as a share of GDP between 2022 and 2024, sub-Saharan Africa is the only group that is expected to have an increase in revenue during this period (see Figure 8 below).

Figure 8: Almost all regions are forecast to reduce expenditure, but sub-Saharan Africa is the only region that is also forecast to increase revenue

Fiscal consolidation in sub-Saharan Africa

As highlighted by the IMF, sub-Saharan Africa is currently subject to a funding squeeze due to rising borrowing costs and a reduction in foreign aid flows, just as the region is recovering from a series of crises that have left it vulnerable. Around two-thirds of countries in the region are planning some form of fiscal consolidation (reduction of expenditure or increase in revenues of at least 1 percentage point of GDP), although there is considerable variation in the trajectories of revenue and expenditure (see Figure 9). What can we expect from fiscal consolidation in the region?

Figure 9: Despite a wide range, fiscal consolidation is under way in sub-Saharan Africa

Although public sector wage expenditure is relatively protected, some countries such as Chad, Guinea-Bissau, Mozambique and Namibia are planning cuts to the public sector wage bill of over 1% of GDP between 2022 and 2024. Relatively speaking, evidence suggests that cutting public sector wages is more benign in its impact on economic growth. Nevertheless, it is a politically difficult approach – especially in a high-inflation environment – and may affect the provision of much-needed public services.

Public investment is forecast to be more volatile. While many countries in sub-Saharan Africa are expected to preserve public investment, some are planning significant cuts. In particular, Burkina Faso, Malawi, Sierra Leone and South Sudan are forecast to cut public investment by more than 2% of GDP. Benin, Botswana, Ghana, Mozambique and Tanzania are also expected to implement significant cuts. This is worrying given the evidence that cuts to public investment could have a detrimental impact on future economic growth as compared to cuts to public consumption (Arizala et al, 2017; Ardanaz et al, 2021).

Figure 10: Some countries in sub-Saharan Africa are planning sharp cuts to public wages and investment expenditure

Looking forward: building resilience in an age of austerity

The macroeconomic environment has changed radically compared to what was expected pre-Covid, with governments still in the process of unwinding the exceptional level of fiscal support provided in response to the pandemic.

Not all countries had the same experience: sub-Saharan African countries, notably, did not increase expenditure as much as other regions during the pandemic. However, due to a combination of high prior levels of indebtedness, heightened inflation and interest rates, currency depreciation and reduced aid flows, many are having to tighten fiscal policy. Unlike other regions that are forecast, on average, to only tighten expenditure, sub-Saharan Africa is expected to resort to both expenditure reductions and revenue increases, which will lead to difficult choices in the future.

In contrast to the spending cuts we are actually seeing, a large and sustained investment push is required to address climate change and get the Sustainable Development Goals back on track. It has been calculated that emerging market and developing economies (excluding China) require additional domestic revenues of 2.7% of GDP above 2019 levels by 2025 (or $653 billion) in areas including sustainable infrastructure, the acceleration of energy transitions, climate adaptation and resilience (Bhattachartya et al., 2022), as well as large increases in official development assistance and non-concessional lending by multilateral development banks.

Some tools have been created to address the challenge, such as the IMF’s new Resilience and Sustainability Trust – although there have been relatively few disbursements to date. The international community may need to do much more to help vulnerable countries put their public finances on less painful paths to sustainability without compromising progress against their development goals.