UK Chancellor of the Exchequer Jeremy Hunt has ruled out any increase to the UK aid budget in the next five years.

But the government’s own independent fiscal forecasts showed that the two fiscal tests for increasing aid spending would be met within this period. More broadly, the level of aid spending should not depend on such fiscal gimmickry, and the Autumn Statement also contained problems with how the UK forecasts future spending. The UK needs realistic expenditure forecasts and, within this, a credible commitment to aid spending that provides some stability and certainty to both UK aid spending and to the country’s global partners.

The OBR is forecasting that the two tests to return UK aid to 0.7% of GNI will be met in 2027-28

In 2021, then-Chancellor Rishi Sunak set out two tests to return the UK’s official development assistance (ODA) to 0.7% of gross national income (GNI). These require the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR)’s fiscal forecasts to show that, on a sustainable basis:

- the government is not borrowing for day-to-day spending (i.e. there is a current budget surplus)

- underlying debt (public sector net debt excluding the Bank of England) is falling as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP)

While the Autumn Statement confirmed that these conditions were not met for 2024-25 (see paras 2.23 and 5.10), it did not say anything about whether they would be fulfilled over the rest of the five-year forecasting period (i.e. to 2028-29).

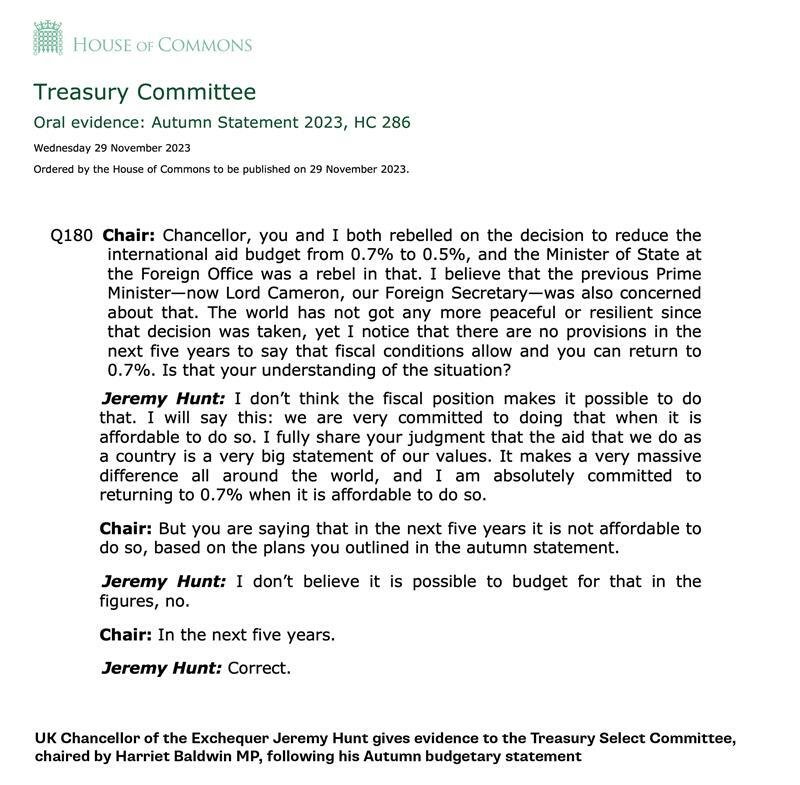

Appearing before the UK Treasury Select Committee on 29 November, Mr Hunt went further and ruled out any return to 0.7% within this timeframe forecast, saying: ‘I don’t think the fiscal position makes it possible to do that…we are very committed to doing that when it is affordable to do so.’

This would seem to contradict the OBR’s forecasts, which show that the two tests will be met in 2027-28 – two years before the end of the current five-year forecast.

By 2027-28, the current budget deficit will be eliminated (meaning that the government will not be borrowing for day-to-day spending) and underlying debt will be falling (albeit by the narrowest of margins).

The gap between Mr Hunt’s statement and the OBR’s forecasts are symptoms of the fiscal fictions that are pervasive in wider UK public finance debates, but especially on the subject of aid.

Aid spending should not rely on fiscal gimmickry

These forecasts demonstrate the problems in relying on such fiscal gimmickry to guide spending. Should the decision to set ODA spending at 0.5% or 0.7% of GNI really depend on whether the current budget has a 0.2% of GDP deficit (as is forecast for 2026-7) or a surplus of 0.3% of GDP (as is forecast for 2027-28)? Similarly, should it depend on whether the debt-to-GDP ratio falls by 0.05% of GDP (as is forecast from 2026-27 to 2027-28)? Spending decisions should not be made on the basis of whether large aggregates with uncertain forecasts creep into positive or negative territory.

The government may reply that Mr Hunt’s remarks have no bearing on the decision over whether these tests are met or not as it has only committed to making an assessment the year immediately before any increase in aid (hence why the Autumn Statement only confirmed that the tests are not met for 2024-25). But this makes things worse. It means that, taken at face value, the government is committed to increasing spending to 0.7% – a 40% rise in the aid budget – in a single year. Just as the ODA cuts led to bad decisions and were detrimental to the UK's standing and reputation with bilateral partners, so a rapid scale-up in aid would be both extremely difficult to implement and unlikely to result in effective spending decisions.

The fiction of the fiscal forecasts

The Autumn Statement revealed a broader problem with how the current budgetary set-up treats medium-term spending plans. To date, the government has outlined detailed, department-by-department spending plans until 2024-25 only. For the final four years of the fiscal forecast, there are only aggregate totals. As Richard Hughes, Chair of the OBR, has said: ‘there aren't any spending plans, there are four numbers’.

The assumptions the government has asked the OBR to make on these numbers imply a fall in spending as a proportion of GDP at a time when public services are struggling. The OBR says that delivering these spending reductions would ‘present challenges’ and, as a result, ‘the Government’s post-Spending Review plans present a significant risk to [its] forecast’. The UK’s Institute for Fiscal Studies warned of ‘a material risk that those plans prove undeliverable’, while other observers have been more blunt, calling them ‘completely undeliverable’.

Fiscal fictions, 0.7% and the two tests

The debate around the aid budget is caught up in these broader fiscal fictions. On aid, the Tory fiction is that there is a serious set of tests that determine when 0.7% is affordable and that set an appropriate path for aid spending. Mr Hunt’s remarks at the UK Treasury Select Committee suggest he does not take these tests seriously. Moreover, they do not set an appropriate path for spending.

The Labour fiction is that, politically they have to pretend to agree with an unrealistic set of spending forecasts to avoid being accused of wanting to borrow more or raise taxes. Then-Chancellor Gordon Brown stuck with his predecessor Kenneth Clarke’s extremely tight spending plans in 1997, and it seems that current Labour Shadow Chancellor Rachel Reeves intends to emulate this. On aid, this means that Labour is unable to commit to 0.7% now as it is hard to treat aid differently from any other spending commitment.

The fiction that the UK development sector must abandon is that a legislated 0.7% target is a useful mechanism for maintaining high and stable aid spending. It has been increasingly devalued since a rising proportion of aid has been spent domestically. If a government is not committed to aid spending, there is simply the incentive to report as much domestic spending as can be legally reported as aid, leaving the real aid spending that targets poverty reduction to fluctuate in response. The UK must move on from a system where, should the costs of hosting refugees rise in a given year, the UK Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) is expected to find corresponding savings in its aid spending.

How to move beyond the fictions

More broadly, if the future path of public spending is not credible, then neither is that of aid spending. The government has funded tax cuts by assuming an unrealistic total for public spending. Rather than basing future spending forecasts on a baseline – an estimate of future spending assuming the continuation of current policy – a level future spending has been assumed, with no announcement of the policy changes that will be needed to meet those spending levels. Use of a proper expenditure baseline in UK fiscal forecasts, rather than Treasury-mandated assumptions, would allow for more serious discussion of the future path of all spending, including aid.

But aid spending in particular must move on from fiscal gimmickry. The recent White Paper on International Development seemed to be partially aimed at demonstrating that the UK can once again be considered a reliable partner on the international stage. After the difficulties caused by several rounds of aid cuts and the merger of the former Department for International Development with the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (creating FCDO), the paper committed to more equitable partnerships and spoke of the importance of ‘mutually respectful relationships’ and ‘working closely with partners’.

It is difficult to see how this can be reconciled with the current framework for aid spending. Large year-on-year yo-yos in spending will not result in reliable partnership or high-quality spending. No other department is expected to cope with such large swings. A new framework must be established that separates spending with large fluctuations from core aid spend such as catering for refugee in-flows (fiscal anoraks will note that the government does this for other forms of welfare spending that are managed as annual managed expenditure rather than departmental expenditure limits). Why should FCDO uniquely have to bear these risks when other departments are not expected to?

Opinions may vary on whether getting back to 0.7% ODA is ‘affordable’ or not. The OBR reports that this would cost around £6 billion in 2028-29 – equivalent to roughly 0.5% of the government’s overall spending forecast of £1,373 billion. But government should put in place a credible commitment to aid spending that it feels it can meet, not a legislative target devalued by fiscal gimmickry. The 0.7% ODA target has become another victim of Goodhart’s law. Instead, we need a serious debate on what the medium-term path for aid spending should look like, based on the fiscal situation and on the UK’s development policy ambitions.