With around 40% of the global population heading to the polls this year, 2024 looks set to be a year of profound change. While understandably buried beneath the headlines on Trump, Sunak, and Modi, 2024 is also the year in which the international community promised to align on the most consequential catalyst for achieving the goals of the Paris Agreement - the New Collective Quantified Goal on Climate Finance (NCQG).

But in order for the NCQG to work, States must determine, among other things, the goal's 'access features' - that is, how and via what channels a recipient country actually secures this finance; an issue that goes to the heart of realising fairness and equity in the world’s response to climate change.

The concept of access touches not only on who receives this finance but also how and when they receive finance. This feature is, therefore, as important as other debates on the quantum and other qualitative features of the NCQG. Because even if the quantum is in the ‘trillions’, it is of little use if the finance is not received by the right recipients at the right time through the right process. Additionally, improving access to climate finance increases the likelihood that the money will be used well.

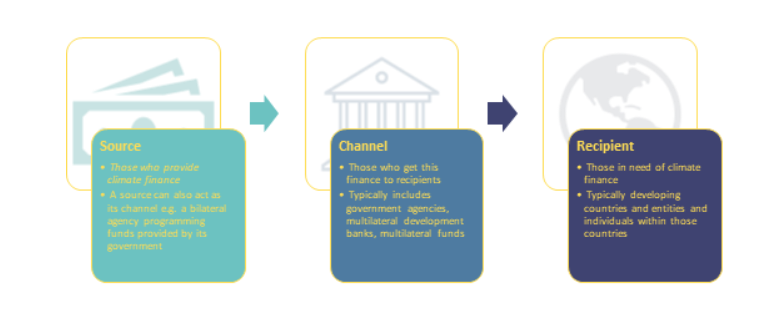

This blog examines the processes that relevant actors go through in exercising the right to use - or obtain benefit from - climate finance from public sources. As outlined in the Figure below, these relevant actors include: those in need of climate finance (recipients), those who provide climate finance (sources), and those who get this finance to recipients (channels).

The enhancement of ‘access’?

The international climate change regime has sought to guide the process of accessing climate finance from its inception. This is especially the case for channels that are accountable to the UNFCCC regime (i.e. Global Environment Facility, Adaptation Fund, Green Climate Fund, and Loss and Damage Fund). However, these multilateral climate funds are not the only channels through which developing countries can receive climate finance. Bilateral, regional and other multilateral ones exist outside of the regime.

The calls from the UNFCCC regime on this topic have been relatively constant. But the calls have typically been high level and gave great latitude to the authorities governing the access channels, from UNFCCC funds which are required to take into account the regime’s annual guidance, to bilateral, regional and other multilateral channels which get invitations to reform their access processes.

For example, the UK COP 26 presidency arguably led one of the most robust attempts to reform access. As COP President-Designate in 2020, Alok Sharma signalled the importance of this matter at the UNSG Climate Ambition Summit. Then followed ministerial meetings, an external taskforce, think tank commissioned research, dedicated action for the 2021 climate finance delivery plan, as well as a set of external principles & recommendations with accompanying pilot projects on the topic.

While these and other efforts have raised the urgency of ‘access to climate finance’ on the international stage, there are still many problems plaguing the architecture including those related to the channels’ processes and coordination, the channel’s trust of the recipient, and the recipient’s capacity.

Fragmentation of access channels and their uncoordinated efforts: A old story of ‘darlings’ and ‘orphans’

For development finance, ‘fragmentation’ is when finance comes in too many pieces from too many channels, creating high transaction costs and making it difficult for recipients to effectively manage their own development (See OECD Report for further details). It leads to ineffective finance provision and the ‘accumulation of providers in some countries (darlings) and gaps in finance provision in others (orphans)’. This is seen at the global, national, and sector levels.

One of main drivers of fragmentation is that the sources and channels of both development and climate finance ‘decide individually which countries to assist and to what extent’. And – as found in our recent report on sources of funding for climate finance – those sources predominantly decide how they will allocate resources based on a combination of factors: legal obligations, a spirit of solidarity, and the pursuit of national interest. The aggregate result is the piecemeal rather than strategic provision of finance.

Similar to what was established for development finance, sources and channels providing access to climate finance could potentially benefit from some sort of international directives centred in achieving international climate goals while taking in account developing countries needs and priorities, and being guided by the regime’s principles. Stricter, more strategic directives can arguably assist in coordination and harmonization among these channels and sources. The NCQG provides an opportunity for the UNFCCC regime to provide these directives and other access-related features in the context of its new climate finance goal.

Putting the puzzle pieces together: Strategic division of efforts amongst access channels and their sources

The fragmentation of the climate finance architecture means that scarce concessional resources are not used well. Some ‘darlings’ - whether countries or sectors – receive an outsized share of climate finance, while some ‘orphans’ are under-served. Poor communication among channels and their sources, and within countries leads to duplication of effort and other less strategic spending and investment.

In order to combat fragmentation, it is important to establish a more strategic division of efforts among channels and their sources of funding. Better coordination is needed at a global scale, to ensure an appropriate allocation of climate finance across recipients and sectors, as well as ensuring that recipients receive suitably concessional funding for their circumstances. Better coordination is also needed at within countries, so that resources flow to where need is greatest and/or transformative potential is highest.

In Article 4(3), the UNFCCC states that developed countries are required to adopt ‘appropriate burden sharing’ among themselves. This is usually understood to mean a fair share of a quantitative target (like the current USD 100 billion goal), but also applies to their responsibility to enhance access to climate finance. Article 9(9) of the Paris Agreement and subsequent UNFCCC decisions also calls for such coordination and harmonization amongst these channels and sources. The NCQG can include features that would enhance coordination and harmonisation, as well as track progress towards a more strategic division of efforts.

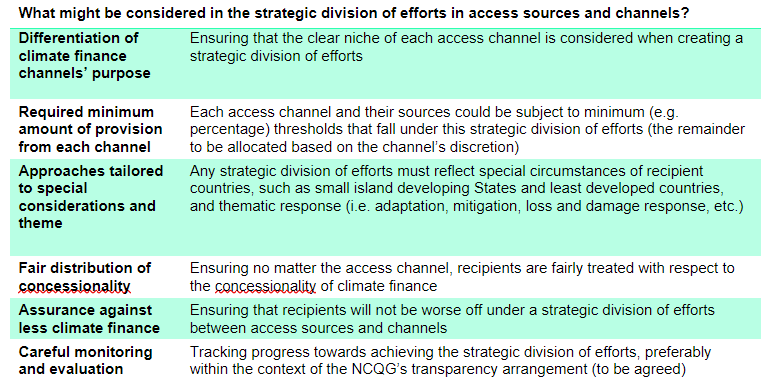

But in developing this access feature, the complexity of the climate finance architecture and the interlinkages with other features like the quantum, quality, timeframe, sources of funding, and transparency arrangements must be taken into account. See table below for a non-exhaustive list of some of these considerations:

Encouragingly, the international climate change regime would not be starting from scratch. Lessons can be learned from the development finance regime and its attempts to have what it called a ‘division of labour’ amongst its access channels. For example, the 2005 Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness and its 2008 Accra Agenda for Action set out four expectations for its access channels and access recipients:

- Recipients taking the lead in determining the optimal ‘division of labour’ of channels at national, regional and sectoral levels,

- The completion of good practice principles on country-led ‘division of labour’ and their evaluation in 2009,

- The commencement of a dialogue on international ‘division of labour’ across countries by 2009, and

- Continued attention towards the issue of ‘orphans’.

Looking Forward

The current climate finance goal failed to engage in any significant way with access to climate finance. Given the blank slate of the NCQG and the growing political will to address this issue, Parties and other stakeholders must seize the opportunity to course correct towards enhanced, efficient, and equitable access to vital climate finance. Concrete mandates for enhancing access must go beyond just the UNFCCC funds. The call for climate finance provision and mobilization from a wide variety of sources and channel must also address access issues within these very actors.

Access is an institutional and governance problem plagued by issues of trust, self-interest, and capacity. When dealing with the provision of such vital finance, we have to be definitive on what is a genuine solution and what is not. Solutions must build trust and capacity; solutions must enhance our ability to efficiently address the climate crisis; solutions must, in plain terms, make things easier. If we veer too far away from this, we arrive at a zero-sum game; where in the case of access, opportunities arise only for a privileged few, not the disenfranchised many.