The climate negotiations in Dubai have wrapped up to a mixed reception.

Sultan Al-Jaber, COP28 President, has hailed the UAE Consensus as a "historic package”. Leading progressive voices are also celebrating the beginning of the end of the fossil fuel era, from the International Energy Agency’s Fatih Birol to one of the architects of the Paris Agreement, Laurence Tubiana.

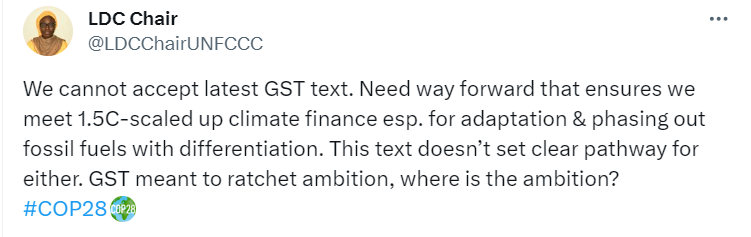

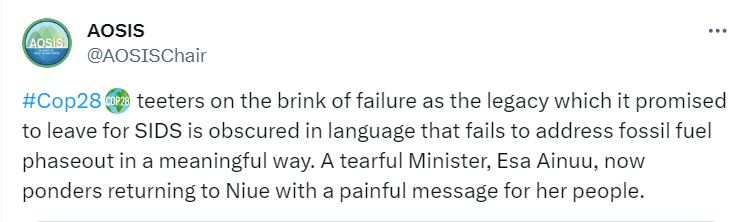

However, the most vulnerable countries have expressed deep concern about the outcome. Madeleine Diouf Sarr representing the Least Developed Countries announced that the deal “reflects the very lowest possible ambition that we could accept”, while Anne Rasmussen representing the Alliance of Small Island States declared that they “were not in the room” and “this text was adopted without us”.

At the start of COP28, we identified six issues to watch during the gruelling two weeks of negotiations. Given the mixed response, let’s examine how the UAE Consensus stacks up. But first, don't forget to sign up to ODI’s Hot Take!, your quarterly guide to all things climate

1. The Global Stocktake

The Global Stocktake (GST) is the five-yearly inventory of our collective progress towards the long-term goals of the Paris Agreement.

The technical report of the GST found that humanity is on track for 2.4–2.6°C of warming, based on announcements made at COP27 in Sharm El-Sheikh. For reference, signatories to the Paris Agreement pledged to limit warming to well below 2°C and ideally to 1.5°C. Even more alarmingly given likely overshoot, the technical report found that adaptation efforts remain “fragmented, incremental” and that financial support fell far short of developing country needs.

In other words, the evidence shows we need a step change in climate action this decade.

The decision text from Dubai – the outcome of a political rather than technical process – cites the science no less than eight times, but ultimately does not make new commitments compatible with a 1.5°C world. (More on this under section 3 on fossil fuels, below.) This explains the deep dissatisfaction of negotiators from the most vulnerable countries, which are already bearing heavy costs at 1.1°C of warming.

Yet it is also clear why many developing countries opposed stronger commitments on climate change mitigation. Of course, a handful of fossil fuel-rich countries are strongly invested in the status quo, such as the Gulf states. But most might adopt bolder climate policies if richer countries put a sufficiently attractive package on the table to help them cover the higher upfront costs associated with lower-carbon forms of development.

While developed countries such as the US, Canada and Australia were vocal about the need for stronger commitments in the decision text, they bring a track record of broken promises on both emission reductions and finance provision. More ambitious pledges in the decision text are meaningless if such large economies cannot be trusted to fulfil them.

At the same time, emission reductions by large, carbon-intensive middle-income countries will also be crucial for limiting warming. As long as actions are commensurate with their “respective capabilities”, there is nothing in the Paris Agreement and indeed the science that justifies this brinkmanship between countries.

The first Global Stocktake therefore does not have the specific timelines, targets and burden-sharing arrangements that might indicate a much-needed course correction – but it is perhaps the best outcome that was politically possible given the schism between developed and developing countries.

2. Loss and damage finance

The agreement to operationalise the new Loss and Damage Fund will stand out as one of the great successes of COP28, and a symbolic breakthrough for climate justice.

The new Fund has already been capitalised to the tune of $700 million. As the first and largest funders, Germany and the United Arab Emirates should be particularly commended for successfully building a bridge between developed and developing country blocs on loss and damage.

Of course, $700 million is well short of the actual scale of loss and damage that countries are already experiencing. As new research from ODI shows, around 39% of economic losses due to weather events in small islands over the last two decades are linked to rising temperatures, amounting to some USD 41 billion. Looking forward to 2050, floods and storms in these vulnerable regions are forecast to cause another $56 billion of loss and damage that can be attributed to climate change.

While the operationalisation of the Loss and Damage Fund has been widely welcomed, the most vulnerable countries have reasons for concern about its design, particularly its new home within the World Bank. The decision text from COP28 puts in place eleven conditions to assuage these concerns – but will they be sufficient?

In one of ODI’s rolling insights into the climate negotiations, Michai Robertson and Bianca Getzel examine the Bank’s policies and track record in managing climate funds, and flag some potential challenges:

- How much autonomy will the Executive Director and Secretariat personnel have, considering that they will be Bank employees? How will this curtail the risk appetite of the Fund?

- What cost recovery methodology will the Bank use? Will it increase its overhead fees at short notice as it has done for the GEF?

- How will the Bank handle private contributions from corporations, foundations and individuals, which could increase the resources available for addressing loss and damage?

- Will the Bank embrace the ‘direct access’ modality? As shown in the graphs below, both the Green Climate Fund and Adaptation Fund have seen funding flowing directly through national entities stagnate since 2020 relative to funding flowing through international entities.

3. Tackling fossil fuels

In the last few hours of COP28, the language around fossil fuels (within the GST) received the most scrutiny. Progressive governments and civil society observers had long been concerned about the UAE’s conflict of interest and the prominence of oil interests at the conference, and their fears proved well-founded with weak draft decision texts emerging from the COP28 Presidency’s office.

However, pressure from a large majority of countries and a vocal civil society secured stronger language in the final decision text, specifically a call to:

[Transition] away from fossil fuels in energy systems, in a just, orderly and equitable manner, accelerating action in this critical decade, so as to achieve net zero by 2050 in keeping with the science

The inclusion of fossil fuels is a major milestone compared to previous COP decisions. But the text remains far short of what is needed to limit warming to well below 2°C, let alone to achieve this temperature target in an equitable way.

For example, coal is the most polluting fossil fuel and there are few viable decarbonisation pathways that do not quickly phase out its use while remaining within the carbon budget for 2°C, let alone 1.5°C. But the immediate emphasis on coal (vis-a-vis oil and gas) puts the onus of decarbonisation this decade upon middle-income countries like China, India, Indonesia, Pakistan and Vietnam, rather than some large high-income economies that are both richer and have emitted more greenhouse gases per person, like the US, the EU, Canada, Qatar and the UAE. Meanwhile, the enthusiasm for carbon removal technologies and transition fuels (read: fossil gas) provides loopholes for the fossil fuel industry.

The imperative of collective action today reflects thirty years of inadequate climate leadership from much of the developed country bloc, both enabled and driven by a disinformation campaign by fossil fuel interests. Wealthy countries such as the US, Canada and Australia might have called for a phase-out of fossil fuels in Dubai, but they have done little to slash emissions domestically to date and indeed plan to expand fossil fuel production. They have also failed to provide either the finance or technology that many low and middle-income countries need for a low-carbon energy transition. Meanwhile, many developing countries hide behind a crude binary interpretation of the principle of “common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities”.

Even though renewables increasingly represent the least-cost marginal energy source, the upfront capital need is greater and financing costs in developing countries can be unacceptably high. For many (though clearly not all) developing countries, this creates a steep trade-off between sufficient energy and clean energy, making it much harder to commit to a fossil fuel phase-out. If developed countries seriously want to see a fossil fuel phase-out in the decision text at COP29, they will need to step up dramatically in 2024—especially on finance.

4. The Global Goal on Adaptation

The inclusion of a Global Goal on Adaptation in the Paris Agreement was a hard-fought achievement, especially for African countries. However, the Goal as articulated in the Paris Agreement is very high-level, so a global work programme was launched two years ago to secure greater international effort and buy-in into understanding what effective adaptation looks like and how we measure progress.

Negotiators have found it very challenging to set ambitious, measurable global targets given that adaptation is often inherently local. (Indeed, after two years of dialogue among experts and negotiators, this task remains incomplete: the GGA decision text commits to a further two-year work programme to identify potential indicators.) The good news is that the GGA text now lays out voluntary targets that reflect common areas for reducing climate risks across societies and ecosystems, which should help focus minds – and resources.

During COP28, ODI’s Mairi Dupar launched Stories of Resilience: Lessons from Local Adaptation Practice. Drawing on lessons from over 200 stories on the ground, she illuminated how international actors and national policymakers can best support locally-led adaptation through centring human rights and directly addressing the underlying drivers of vulnerability, such as exclusionary social norms. Mairi’s findings also underscored the importance of respecting diversity in community approaches and empowering local decision-makers.

As Mairi explains, all of these objectives benefit from patient, predictable finance; supportive legislation; and sustained capacity building. And although the framework for the GGA ticks many other boxes, the ultimate test will be whether it helps to raise and steer the resources that frontline communities so urgently need to adapt to a more hostile climate.

5. Quality assuring climate finance

The decision text emerging from COP28 is threaded through with concerns about the quantity and quality of international climate finance reaching developing countries. For example, the Global Goal on Adaptation “notes with concern” that the adaptation finance gap is widening and “reaffirms” the need for grant-based funding for adaptation.

While climate finance did not gain the same attention in Dubai as in Sharm El-Sheikh and Glasgow, the historic shortfall towards the $100 billion annual climate finance goal agreed in Copenhagen still had an insidious effect on climate ambition. As outlined above, many middle-income countries that are concerned about climate change impacts were nonetheless willing to accept weaker commitments on fossil fuels, as they no longer anticipate sufficient international finance to support their own low-carbon energy transition.

But weak commitments on climate change mitigation are a ‘death certificate’ for the Small Island Developing States and Least Developed Countries.

Small islands are already seeing their credit ratings downgraded due to perceptions of higher risk, as Emily Wilkinson and Kanni Wignaraja write in Project Syndicate, further eroding their ability to invest in mitigation or adaptation.

COP28 therefore underscores that the provision of sufficient, decent climate finance is not just a moral or legal imperative. It is politically and financially essential to enable climate action in low- and lower-middle income economies, and thus to have any hopes of limiting warming to well below 2°C.

The fight will continue at COP29 in Baku, Azerbaijan, where the new climate finance goal should be finalised.

6. Scaling climate finance for conflict-affected states

The Climate, Relief, Recovery and Peace Declaration was launched in the middle of COP28, calling for “bolder, collective action” to scale up climate finance and action in fragile and conflict-affected countries. These are some of the most climate-vulnerable places in the world, but receive far less climate finance than more stable countries.

As Mauricio Vazquez and Yue Cao write in one of ODI’s rolling insights into the climate negotiations, the conversation about scaling up climate action in conflict-affected countries was barely a whisper just two years ago. Now concern about how climate change will further impact these vulnerable communities has become mainstream. The Declaration has already been endorsed by over 70 states.

Going forward, the challenge will be not just to scale up climate finance to these areas, but also to build meaningful climate resilience in the long term. The Declaration should be seen as an opportunity for different actors – working across climate, humanitarian, peacebuilding, development and disaster risk management – not just to request more funding for individual projects, but also to collaborate on more joined-up, risk-informed work which lays the foundations for climate-resilient development.

Conclusion

The UAE Consensus has many welcome elements: a plan for the Loss and Damage Fund, a call to transition out of fossil fuels, a framework for the Global Goal on Adaptation.

Perhaps this is the best possible outcome given the unfavourable context and the constraints of the climate architecture. Negotiators arrived in Dubai against a backdrop of conflict, trade wars, a debt crisis and a backlog of unfulfilled promises within the climate regime. The UNFCCC process then required them to secure consensus, which has long allowed climate ambition to be held hostage to vested interests.

The UAE Consensus certainly does not close either the ambition gap or the implementation gap. Fortunately, however, the international climate negotiations are no longer the driving force for climate action (though they generate valuable scrutiny and energy for more decentralised initiatives).

Now we are seeing country-specific narratives and supportive policies emerging in countries at all levels of income, including those that have not necessarily been champions within the UNFCCC. China has emerged as the green factory of the world, dominating the production of solar panels, wind turbines and electric vehicles. The US is injecting $379 billion into low-carbon manufacturing via the Inflation Reduction Act. India has embraced solar power and is preparing for hydrogen. Opportunities to enhance energy security, tackle air pollution and create jobs are galvanising strong climate policies where international expectations have long failed to unlock action. But this change remains too slow, unfortunately, to match the urgency of a depleting carbon budget.

Even international climate finance is no longer primarily subject to COP decisions, as Michael Jacobs notes in one of ODI’s rolling insights into the climate negotiations. Decisions are made instead at the G20 Summits, the IMF/World Bank meetings and in meetings of the Paris Club of creditors. The climate community has therefore rightly turned its attention to these forums, given that access to finance for developing countries will make or break our collective hopes for a climate-safe world.

To follow ODI’s cutting-edge research and influential convening in this space, don’t forget to sign up to our quarterly climate newsletter, Hot Take! Happy holidays and see you in 2024.