‘We promised, and we delivered,’ announced Kristalina Georgieva last year when the International Monetary Fund (IMF) began lending through the new Resilience and Sustainability Trust (RST).

The RST is the IMF’s signature effort to respond to the global climate challenge, borne out of the G20 pledge, made almost two years ago, to rechannel $100 billion of Special Drawing Rights.

The IMF may have delivered against its own expectations. It created a new instrument and it is close to meeting its fundraising target. The aim was to raise at least SDR 33 billion (equivalent to $45 billion) for the RST. As of 30 June SDR 31.2 billion had been pledged (about $41.5 billion). This is in addition to the $16.9 billion (SDR 12.6 billion) in loan resources and $1.9 billion (SDR $1.4 billion) in subsidy resources commitments to the IMF’s Poverty Reduction and Growth Trust (PRGT).

Delivery, of course, should not be judged against fundraising targets, but on whether the funding is increasing ‘resilience and sustainability’ as intended. Here the picture is less rosy. The design of the Trust means that the IMF has been unable to ratchet up financing despite a series of cascading shocks. Where programmes have been approved, they have typically involved fiscal retrenchment, which runs counter to a narrative of investing in future resilience. Finance ministries are also being burdened with a whole series of additional conditions to reform national-level institutions to counter global risks over which individual countries have limited control.

This should not come as a surprise: the IMF is much less well-equipped to design operations of this nature (essentially a form of climate-linked budget support) than the multilateral development banks (MDBs), which have a much broader range of competencies and mandates better suited to this work. Instead, shareholders should look at how SDR pledges could be used to enable the IMF to play its core roles more effectively in an era of increasingly frequent shocks.

Why was the Resilience and Sustainability Trust created?

At the outset, it is important to acknowledge that the RST – and its specific design – was borne out of a set of particular political circumstances. Back in October 2021, the G20 committed to rechannel $100 billion-worth of SDRs ‘to support vulnerable countries affected by the COVID-19 pandemic’. This commitment showed a willingness to provide additional financial support without G20 countries having to make further fiscal commitments.

The practicalities of rechannelling SDRs have not proven easy. As their custodian, the technical barriers to the IMF on-lending SDRs are lower than for other multilateral financing institutions. The IMF already had a track record of ‘on-lending’ SDRs though the PRGT, and so it was a natural front-runner for ‘rechannelling’.

There are, however, limits to the PRGT’s absorptive capacity. A key constraint relates to the Trust’s funding model, which requires subsidies to cover the costs of providing interest-free loans. As interest rates have risen globally, the costs of the subsidy needed to maintain the zero interest rate have also grown. Pledges of SDR loans have been generous, but the fiscal commitments to cover the subsidy much less so. Even if the PRGT was fully funded, earlier demand forecasts had estimated that it could only reasonably absorb $2.4–$4.3 billion per year because of the scale of the economies in question (the PRGT is primarily targeted at lower-income countries), their ability to carry additional debt given rising debt vulnerabilities, stigma attached to borrowing from the IMF (many countries do not want to subject themselves to an IMF programme) and access limits to the Trust (although the IMF is considering revising these).

There was also a view that the international financing response to Covid had revealed insufficient financing support for vulnerable middle-income countries. Signature measures such as the Debt Service Suspension Initiative targeted lower-income countries in the same way as the PRGT and the World Bank’s IDA. The IMF was also coming under pressure from civil society to do more to support governments with respect to the macroeconomic threats posed by climate change.

The creation of the RST provided a means for the IMF to increase its overall concessional lending using SDRs, and to link that lending more explicitly to climate. Eligibility requirements are broader: 143 countries are eligible for financing through the RST, as against 70 for the PRGT, and unlike the PRGT the economies in question include countries with higher average income levels such that they could sustainably absorb larger volumes of external financing (see Table 1). RST loans also have longer maturities relative to the PRGT and borrowing through the general resource account. This means that new loans do not add to the immediate short-term external debt burden and so can potentially increase an individual country’s overall capacity to borrow from and comfortably repay the IMF. Longer maturities were also more consistent with a narrative of ‘strengthening resilience’.

Has the Resilience and Sustainability Trust been effective?

It is obviously still early days, but we would argue that the RST is falling short of expectations in three key areas.

1. The volume and take-up of external financing through the RST is low

While the RST has the potential to increase lending capacity, as of yet this has not obviously translated into overall increases in net IMF lending. Following a surge in disbursements in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic, IMF funding has dropped sharply (with the exclusion of Argentina, which has dominated IMF flows in non-pandemic years, and Ukraine, which has featured prominently since 2022). Disbursements through the RST are still barely discernible two years on from the G20 commitment. Overall lending remains somewhat high relative to pre-Covid, but the lack of financing is surprisingly dissonant with the scale and gravity of the reverberating crises that have followed Covid-19.

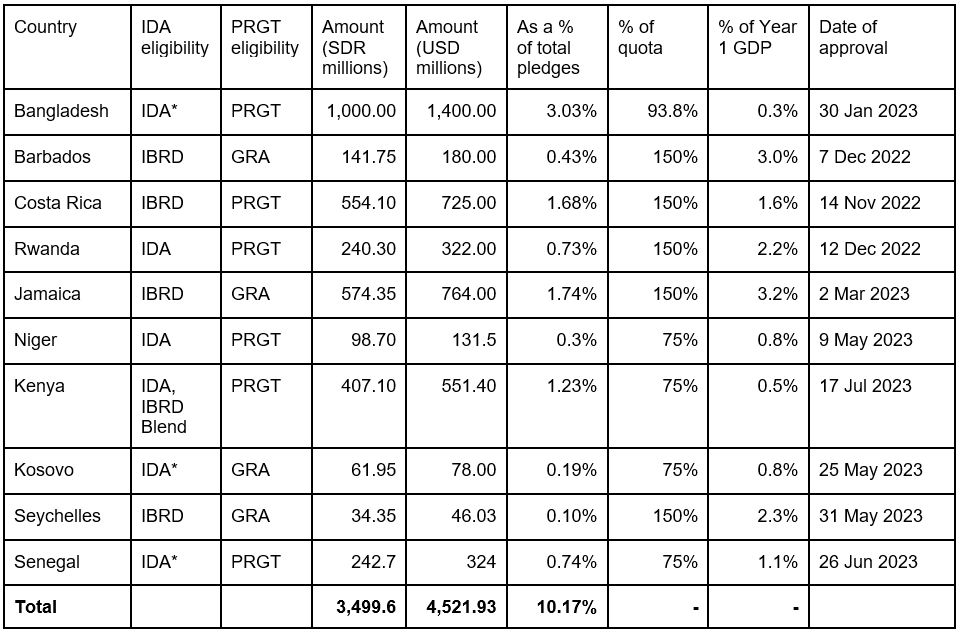

In part, this is because of the slow pace of approval for new programmes. Table 1 shows that, as of 30 July 2023, only 10.17% of total anticipated pledges had been committed to countries. Despite stated demand for funding from more than 40 countries, the IMF has been unable to ratchet up the pace of new programme approvals. This is primarily because funding through the RST requires the approval of an Upper Credit Tranche (UCT) instrument. Unlike the Rapid Financing Instruments used in the wake of Covid-19, UCT programmes are not quickly approved as countries are negotiating over binding macroeconomic targets.

Table 1: Scale of programmes as % of quota, % of GDP and relative volume vs. size of pledges

The RST has also not attracted a wave of new borrowers to the IMF. With the notable exception of Rwanda, to date the RST has provided more IMF financing for countries with existing IMF programmes. The Trust is effectively being deployed as a new arm of adjustment lending (albeit one that does admittedly improve the overall financing terms the IMF can offer as a package, particularly to countries without access to the PRGT).

2. 'Building resilience and sustainability’ under contractionary targets

The RST’s stated aim is to ‘build resilience to external shocks and ensure sustainable growth, contributing to their longer-term balance of payments stability’. A key way to build resilience is through investment. As stated in the Bridgetown Initiative, crises have ‘systemic roots’ where ‘[o]nly investment will change their course’.

One might therefore expect to see RST programmes enabling relatively expansionary fiscal policy geared towards investing in greater resilience and sustainable growth. We might anticipate programmes that enable temporarily larger primary fiscal deficits with increased public investment and a temporary worsening of the current account and trade balance to import necessary capital goods for investment in resilience.

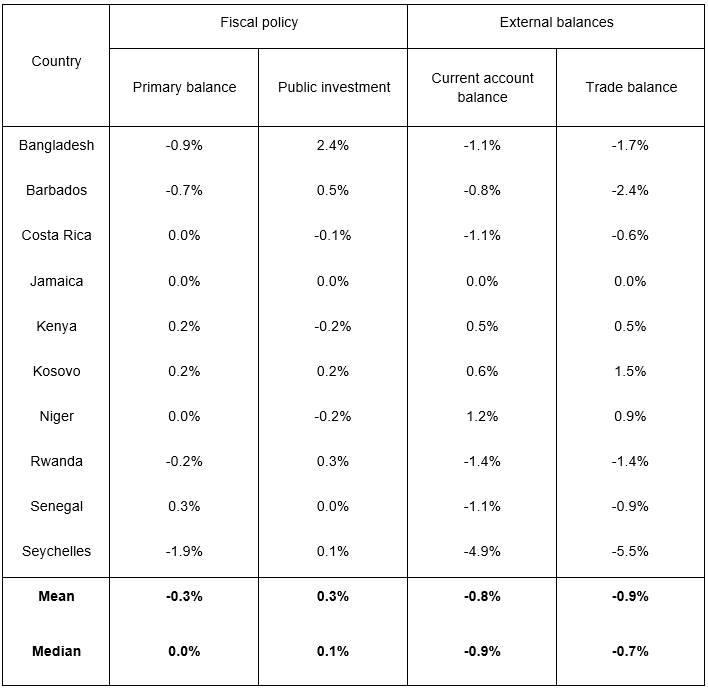

Yet looking at the programme targets for countries receiving support through the RST, the approach appears to be one of saving for a rainy day, rather than increasing investment in future resilience.

The dots and arrows in Figure 3 show the starting points and changes in the current account and primary balances in the years that funds from the Trust are being disbursed. It shows that five of the 10 countries where the RST has been approved are expected to run primary surpluses (this means raising more in taxes than spending excluding interest payments). Furthermore, almost all countries are on a trajectory of fiscal consolidation during the course of the RST programme. Equally, although all countries run a current account deficit, all but one are on a trajectory of (sometimes sharp) narrowing. In other words, despite the additional lending provided through the RST, the overall fiscal and external stance of countries under the programme is contractionary.

This is not the whole story, of course. Governments around the world are responding to wider global economic dynamics. An approach that favours short-term consolidation over expansion is obviously the result of numerous factors – not least the need to return finances to a sustainable path following the disruption caused by the Covid-19 pandemic, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and a global monetary tightening cycle.

If we compare the first IMF forecasts that include the RST with the last forecast prior to the RST announcement (similar to the approach in Berndt et al. (2008)), we find that, on average, the IMF revises down primary balances and revises up public investment, following RST agreements, while current account and trade balances are revised down. These revisions are more marked in the years of RST disbursement. This suggests that the IMF expects the RST to increase public investment and drive down primary fiscal balances, compared to a situation where the country did not have access to the RST.

Nonetheless, the overall narrative is jarring. Macroeconomic programmes are being agreed with an ostensible objective to increase resilience and sustainability, while demanding governments take steps to find fiscal savings of as much as 3% of GDP. RST programmes appear to be less about enabling investment in building resilience and more about repairing balance sheets before the next crisis hits.

Table 2: Average revisions by country

3. The additional complexity arising from climate conditionalities

A third stated aim of the RST is to support specific structural reforms that strengthen resilience and sustainability. Structural reforms are typically being informed by climate-related diagnostic tests such as the IMF’s Climate Change Policy Assessments (CCPA) and its potential successor instrument the Climate Macroeconomic Assessment Program (CMAP), the World Bank’s Country Climate and Development Reports (CCDR) and the Climate Public Investment Management Assessment (C-PIMA). While it is not strictly essential for a country to have undergone these diagnostic tests to receive RST funding, in practice most countries with approved RST funding so far had either a C-PIMA or a CCDR test.

Table 3: Climate diagnostics for RST countries

| RST countries | PIMA type | CCDR |

|---|---|---|

| Niger | Non-public PIMA | CCDR |

| Rwanda | C-PIMA | CCDR |

| Senegal | C-PIMA | n.a. |

| Kenya | Non-public PIMA | n.a. |

| Bangladesh | Non-public PIMA | CCDR |

| Kosovo | PIMA | n.a. |

| Jamaica | C-PIMA | n.a. |

| Costa Rica | C-PIMA | n.a. |

| Seychelles | C-PIMA | n.a. |

| Barbados | n.a. | n.a. |

The IMF faces resource constraints in rolling out its diagnostic exercises quickly. A recent Fund review of the CMAP notes that demand for climate PFM diagnostic testing is rising rapidly with the operationalisation of the RST. However, the cost of a CMAP is significantly higher than that of a traditional IMF capacity development mission and can be an extra burden on national authorities.

There is a risk that these climate diagnostics may complicate and slow down the agreement of required adjustment programmes. Borrowers who request an IMF programme predominantly for macro reasons might understandably be drawn to the RST (at least in some part) because of the more generous lending terms. If programmes are taking longer to agree because of required climate diagnostic work, in turn delaying the corresponding financing disbursements, the effectiveness of the IMF’s stabilisation function could be undermined.

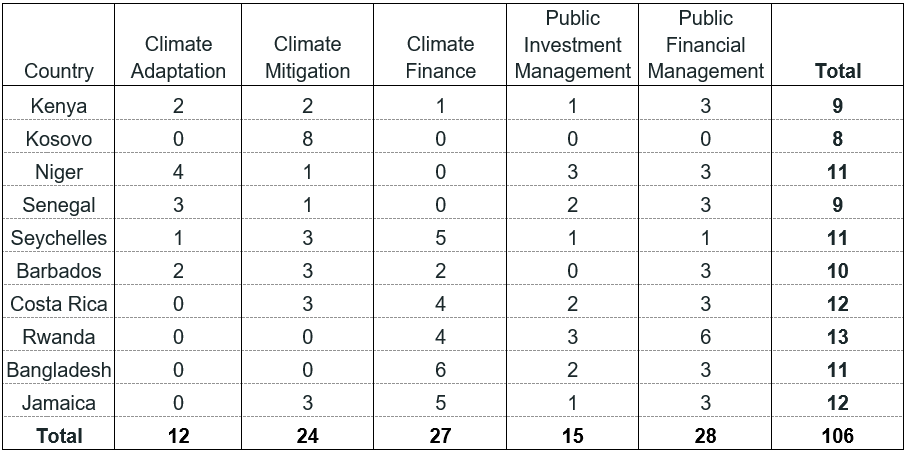

The RST is also contributing to a proliferation of structural conditions in IMF programmes (see Figure 5), which runs counter to the IMF’s agreed direction of travel following the 1997 East Asia crisis. At that time, the IMF was criticised for ‘overdoing it’ when it came to imposing structural and institutional reforms. A ‘streamlining initiative’ followed that urged more parsimony in the use of conditions in IMF programmes.

The reforms appear to be largely concentrated in fiscal and financial functions where the IMF has pre-existing competencies and readily available technical support. This raises questions as to whether conditions are being driven more by what the IMF is good at rather than cross-governmental priorities for building resilience and sustainability. Table 4 groups comparable reform measures included in the agreements so far. It shows that nine out of 10 countries have committed to include some kind of modelling of climate change risk in the budget process, and eight out of 10 to include climate change criteria in selecting investment projects. Some more specific measures, such as climate budget tagging and climate change stress testing of the financial sector, were mentioned in half of the RST agreements.

Table 4: Common reform measures in RST agreements by number of countries affected

|

Reform measures |

Number of countries out of 10 |

|---|---|

|

Climate change fiscal risk analysis/modelling in the budget process |

9 |

|

Climate change criteria for investment projects selection |

8 |

|

Measures to reduce energy use, promote renewables and low-emissions transport |

8 |

|

Develop disaster risk management policy, financing strategy or related tool |

6 |

|

Climate budget tagging |

5 |

|

Climate change stress testing the financial sector |

5 |

|

Guidelines for reporting climate change risk for financial institutions |

4 |

|

Promoting green finance |

3 |

There is a real risk that too many conditions and policy measures could undermine rather than strengthen the resilience of central economic policy-making institutions. For example, the finance ministry of the Seychelles (a set of islands with a population of 100,000) is required to meet more than 30 conditions. The IMF also does not allow for ‘cross conditionality’ with other organisations so these come on top of a separate set of 16 conditions agreed with the World Bank as part of a multi-year Fiscal Sustainability and Climate Resilience loan. In total, the finance ministry has to see through an absurdly ambitious 50 reforms on top of its usual operations.

Linking IMF programmes to climate conditions also runs the risk of raising the political heat surrounding complex issues of intergenerational and international equity. While certain ‘developed countries’ (that are in large part responsible for the stock of carbon emissions today) are consistently deferring investments in emissions reduction, RST borrowers are being required to take actions to reduce emissions right now (Table 5 shows almost a quarter of conditions relate to climate mitigation). Whether or not these actions are endorsed by the government, if the IMF is perceived to be ‘demanding’ emissions reduction as part of broader adjustment programmes, this could lead to concerns around the IMF’s legitimacy and neutrality.

Table 5: Reform measures grouped by type of climate action

What should the IMF’s financing role be in a climate-changed world?

In sum, we have highlighted three causes for concern arising from a review of progress to date on the RST.

- First, the Trust has done little to help scale-up international concessional financing, despite relatively generous pledges of SDR loans.

- Second, where programmes have been agreed, commitments to strengthen ‘resilience and sustainability’ are being grafted on to contractionary programmes.

- Third, a raft of new diagnostics and an array of climate-related conditionalities risk undermining state resilience and adding complexity to traditional adjustment operations.

These problems cannot be fixed by small tweaks to the design of the Trust; rather, the performance of the RST raises more fundamental questions about the role of the IMF in a climate-changed world.

The Covid-19 crisis (which gave rise to the RST) has foreshadowed a world of increasingly frequent global, cross-border crises to which certain types of countries are likely to be particularly vulnerable irrespective of the decisions taken by national policy-makers. In that context, international financial institutions (IFIs) can potentially perform two sets of functions that would help national policy-makers mitigate rising climate concerns:

- First, IFIs could provide increased concessional, long-term financing and technical advice that enables policy-makers to undertake the necessary investments and targeted institutional reforms that could help underpin greater resilience and sustainable growth.

- Second, IFIs could support countries during and in the aftermath of crises to help minimise the depletion of national wealth resulting from external shocks. IFIs could achieve these aims through the provision of liquidity, where necessary overseeing adjustment programmes and coordinating debt restructuring processes.

The RST clearly pushes the Fund more towards the first camp of a long-term development financier, but the Trust’s performance to date suggests that the IMF is not that well placed to deliver against the first goal. Trying to square short-term adjustment objectives with long-term resilience-building is proving to be very messy.

Perhaps even more worrying, there is a risk that the RST is undermining the Fund’s ability to perform the second role, which is more closely aligned to its traditional functions. The spate of climate diagnostics and conditions are complicating and potentially slowing down the agreement of adjustment programmes. The IMF’s role in coordinating debt restructurings is also complicated where it is a significant creditor in its own right.

Shareholders should therefore be wary of additional SDR-linked fund-raising requests for the RST. Multilateral development banks are much better placed to support long-term investment programmes if the funding mechanics can be worked out (through for instance the issuance of SDR bonds). MDBs are also better placed to look at the wider array of structural challenges that will be posed by climate change and efforts to decarbonise the world economy.

Instead, shareholders should be asking the IMF to set out how it can perform its role of crisis financier and adjustment lender more effectively in a world where cross-border shocks and climate disasters are likely to be more frequent.