The Caribbean nation of Antigua and Barbuda will host the Fourth United Nations Conference on Small Island Developing States (SIDS) in May 2024, bringing together world leaders to agree on a bold new 10-year programme of action for small island nations. The stakes have never been higher.

SIDS face an intractable cocktail of issues that threaten to derail their development progress and remove opportunities for future growth. The climate crisis is not the only major threat. A rapidly changing geopolitical and economic landscape – defined by the reassertion of great power politics, the collapse of multilateralism and increasing economic protectionism – will likely reduce options for SIDS to exert influence via their numbers in multilateral fora, or to exploit economic niches. These two strategies have previously been critical to SIDS’ relative success as a group of countries in the past – and are why many have achieved higher-middle income status.

To sustain these gains will be tricky. SIDS will need a strong enabling environment, whereby the international community recognises the special situation of these small vulnerable nations and takes appropriate action to assist them. This support has not always been forthcoming. Since the 1990s, SIDS have sought special and differential treatment (SDT) based on their unique vulnerabilities – with mixed success. The category of ‘small vulnerable economies’ was created in international trade, but it had limited legal standing. Although there have been various SIDS conferences, and there has been recognition of their SDT, small island nations have not enjoyed the same advantages compared to – for example – least-developed countries (LDCs).

Fast-forward to 2023 and there is increasing acceptance amongst donors and international financial institutions (IFIs) that traditional measures of need – those based on GNI per capita – are not appropriate on their own because they do not account for vulnerability to external shocks. Some multilateral development banks (MDBs) have created a special category for SIDS or small states in recognition of this vulnerability. However, with few exceptions, access to concessional finance declines as SIDS achieve higher levels of income and graduate from official development assistance (ODA). This leads to higher borrowing costs with shortened maturities – worsening their fiscal situation. In this era of polycrisis, with tourism decimated and debt rising , a more robust measure for allocating scarce resources is needed.

This is where the United Nation's Multidimensional Vulnerability Index (MVI) comes in. After 18 months of deliberations, and over three decades of lobbying by SIDS, the UN MVI was launched at the 2023 Annual Meetings of the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in Marrakesh, Morocco. The UN MVI measures two things: 1) structural vulnerability (the risk of a country’s sustainable development being hindered by recurrent adverse exogenous shocks and stressors); and 2) structural resilience (the inherent characteristics or inherited capacity of countries to withstand, absorb, recover from or minimise the adverse effects of shocks or stressors). The idea is that this will be a relatively stable index, and therefore more useful for resource allocation than – for example – fragility indices. Proponents of the UN MVI emphasise that it is not a replacement of the GNI per capita measure, but a complement that should inform ODA eligibility and allocations of concessional finance by donors and MDBs.

UN MVI scores show that SIDS have the highest levels of structural vulnerability and a notable lack of resilience compared to all other country groups. The average composite MVI score for SIDS is 56.2, which is significantly higher than the non-SIDS low and middle-income countries (LMICs) score of 48.7, and the upper middle-income countries (UMICs) score of 48.6. On average, 14 SIDS have a composite MVI score of over 60.

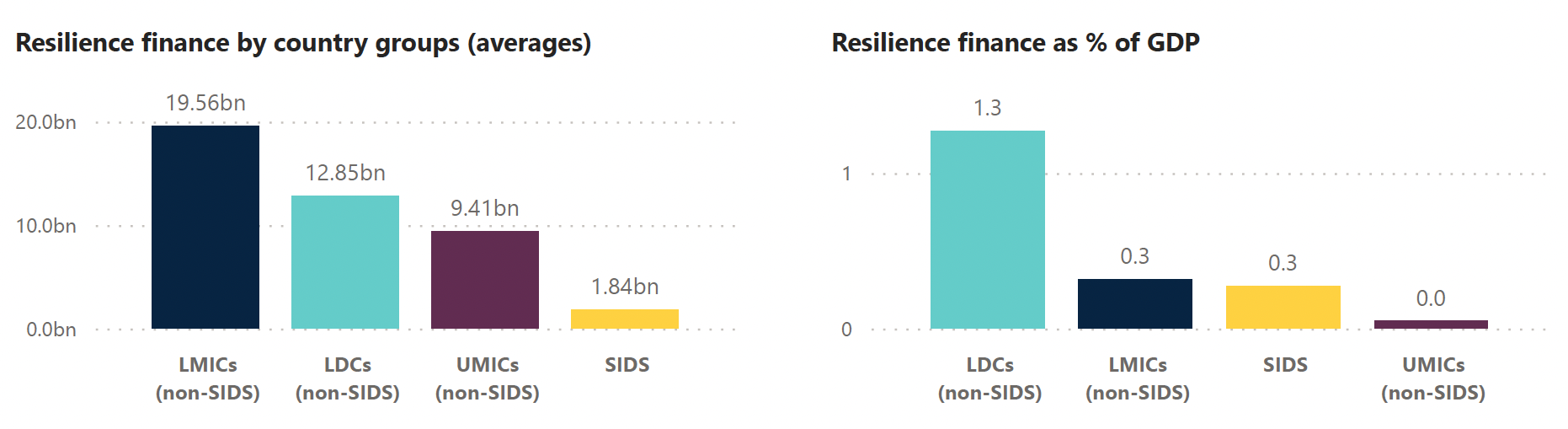

With these scores in mind, this ODI dashboard looks at how international development finance is being allocated to SIDS compared to other groups of less vulnerable countries – focussing on finance that is intended to build resilience. Unsurprisingly, levels of resilience finance for SIDS are considerably lower than for LMICs and LDCs that are not SIDS, even as a percentage of GDP (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Resilience finance to SIDS (annual average from 2013–2021)

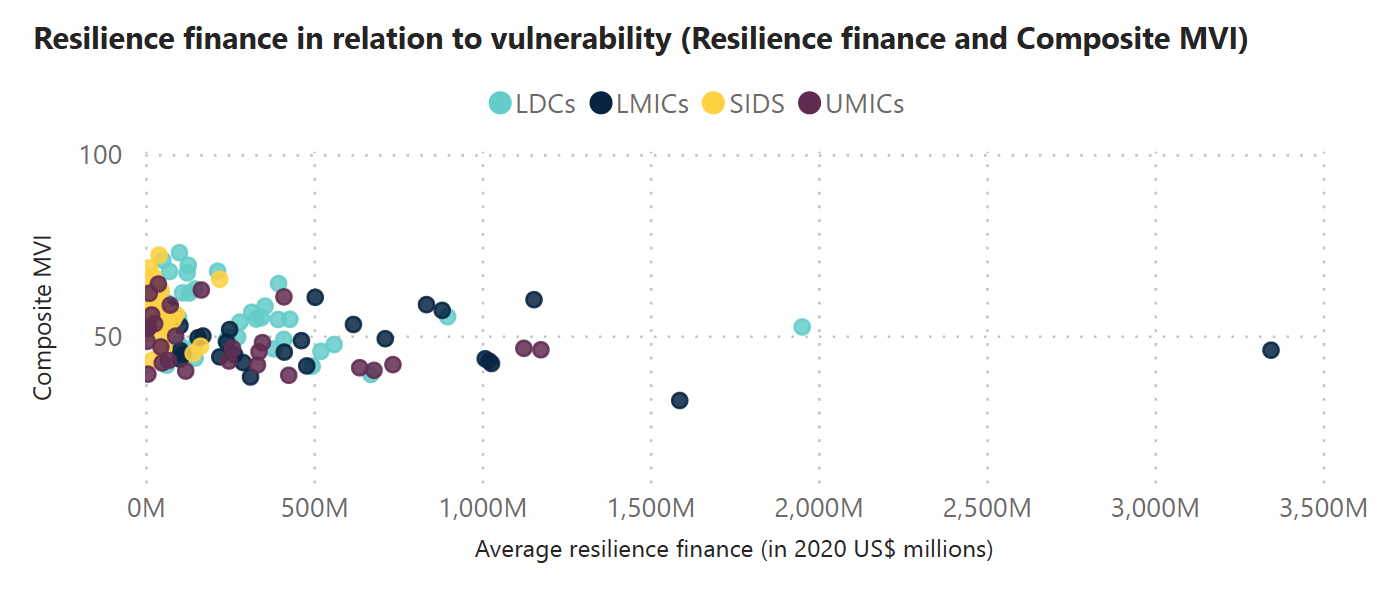

The situation is more striking when vulnerability is considered. On average, SIDS receive significantly less resilience finance than other countries in relation to their vulnerability, as measured by the UN MVI (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Resilience finance in relation to vulnerability (composite MVI scores)

A multidimensional vulnerability index is needed to increase fairness in the allocation of finance for resilience. The UN MVI is one index, but others exist. The Asian Development Fund uses the UN Committee for Development Policy’s Economic Vulnerability Index (EVI) in allocating finance to Pacific SIDS. The UN MVI is an improvement because it focusses on the structural constraints to development that are not only economic, but also environmental and social.

Achieving consensus on an MVI could assist vulnerable countries – and the wider international development community – in adopting risk-informed strategies to build and sustain long-term resilience.