The Ukraine Recovery Conference on 21-22 June, will focus on ‘mobilising international support for Ukraine’s economic and social stabilisation’. Ahead of the conference, Olena Borodyna, Senior Transition Risk Analyst in ODI’s Global Risk and Resilience programme, highlights four of the key geopolitical risks to watch during the country’s post-war reconstruction.

Risk 1: Belligerent Russia poses a continued threat

Limited scope for political change in Russia’s near future means that even when military action ceases, Russia is likely to pose a continuous threat to Ukraine’s reconstruction and security.

Despite speculation about challenges to Putin’s leadership or the state of his health, constitutional changes in recent years mean the current Russian President can remain in power until 2036. It is still unclear whether Russia’s lack of direction in Ukraine will lead to challenges to Putin’s authority, but by escalating war in Ukraine and ramping up narratives about the West and NATO’s threat to Russia’s security, Putin has placed political elites in a difficult position. There is no clear way to move away from that narrative without their own legitimacy being questioned. Meanwhile, the Russian opposition – already limited prior to February 2022 – has been further constrained, with prominent opposition figures like Vladimir Kara-Murza jailed.

As such, the Russian government position on the war in Ukraine is likely to continue, unchallenged on a large scale, for the foreseeable future. Whether it is through cyberattacks on Ukraine’s critical infrastructure or attempted destabilisation of information security, as Russia’s political influence in Ukraine shrinks and pro-Russian parties like Opposition Platform−For Life are dissolved, it may seek other ways of exercising political influence or creating political risks that undermine Ukraine’s effective recovery.

Risk 2: US support to Ukraine, while critical, is a source of great vulnerability

Since January 2022, the USA has provided Ukraine with over $70 billion in military, financial and humanitarian aid. This support from the USA and other allies is critical to sustaining Ukraine’s military efforts and economy, but it is also a source of great vulnerability.

Both former President Donald Trump and his challenger for the 2024 Republican nomination, Florida Governor Ron DeSantis, have so far failed to commit to Ukraine aid. Just months ago, DeSantis described the Russia-Ukraine war as a ‘territorial dispute’ where the US has no national security interest. A storm of criticism from fellow Republicans caused him to walk back on his comments, but his foreign policy stance and proposed course of action on the war remains elusive.

However, both Trump and DeSantis’ rhetoric on Ukraine is targeted at their voter population. Whether their views are endorsed by the wider Republican party remains to be seen. Were either candidate to win the party’s nomination, they would need to square their policies with the trade-offs that securing allies’ support for the US in its strategic competition with China entails, including continued US commitment to European security, and the peculiarities of the US voting system – with Democrats already looking to exploit discontent among Ukrainian-Americans in key swing states.

In the last year, Republicans and Democrats have both sought to reassure Ukraine of USA bilateral support, with delegations of congressional Republicans visiting the country to meet President Zelenskyy. But potential shifts in USA support for Ukraine is a risk that also concerns European leaders, who depend heavily on the USA for ensuring the continent’s security. In recent remarks at the GLOBSEC conference in Bratislava, President Macron betrayed a sense of unease over shifts to the USA's policy on Ukraine, calling for the EU to strengthen its own defences.

Risk 3: Strategic tensions between the United States and China escalate

The recent meeting between the US Trade Representative Katherine Tai and China’s commerce minister Wang Wentao suggests the USA is pursuing a ‘thaw’ in relations with China. The reopening of communication lines between the two countries is a positive step towards rebuilding a relationship which deteriorated after the Trump administration raised tariffs on Chinese imports – to counter unfair trade practices – and upended decades long US foreign policy on China. Most recently, bilateral relations broke down further following the ‘balloon accident’ in early 2023.

However, the USA is still in long-term strategic competition with China – a view shared by many of the countries’ allies including the United Kingdom. This position is unlikely to change with the presidential election in 2024, given prospective Republican presidents would likely maintain or even escalate similar policies.

When it comes to Ukraine’s strategic positioning in this context, it needs to consider the role it wants China to play in the reconstruction of the country. Prior to 2022, China had become Ukraine’s largest trade partner, with investments in agriculture and infrastructure. Now, Chinese investment or other engagement in Ukraine’s reconstruction will likely be controversial with the Ukrainian people, given China’s failure to influence Russia over the invasion – or even talk to President Zelenskyy for the first year after the war escalated. However, Chinese companies have already engaged in Ukraine’s infrastructure projects, and will likely compete for the reconstruction financing projects in the country.

During the Trump Administration, the USA pressured Ukraine to limit Chinese investment in the turbine engine producer Motor Sich. Now, Ukraine may come under further pressure to limit the extent to which Chinese companies benefit from US reconstruction finance, which may be a challenge if they are to remain true to expected procurement procedures.

The USA is not Ukraine’s only ally recalibrating its relations with China. Both the UK and the European Union, for instance, are concerned about their dependencies on China for supply chains of critical raw materials and components for renewables, as well as the risks this creates for their energy security. As Ukraine positions itself as an energy partner to the continent, it will need to consider the role it sees China playing in these sectors. There will be no easy answers to these questions, the country must balance attracting investment and creating prosperity for the population with wider strategic considerations.

Risk 4: Failure to reach beyond allies in the US and Europe

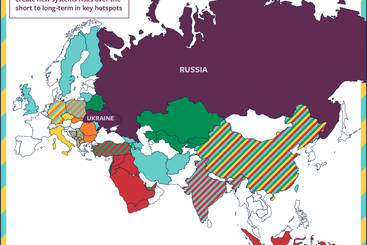

Since the war escalated with a full-scale invasion, Ukraine has enjoyed steadfast support from allies in the USA and across Europe, but reaching beyond existing partners to countries across Africa, Latin America and Asia, will help to counter Russia’s narrative, diversify supply chains and create opportunities in new sectors like digital technology.

Earlier this year, an overwhelming majority of 141 countries supported a UN resolution calling for Russia’s immediate withdrawal from Ukraine, but others including India and China, continued to abstain. Outside the UN General Assembly, only four of fifty-five African leaders joined Zelenskyy’s address to the African Union in June 2022. Since then, Ukraine has stepped up diplomatic engagement across the African continent, with Foreign Minister Kuleba visiting several countries in October 2022, and joining the ASEAN summit for the first timed the following month. However, Ukraine lacks prior engagement with many states and regional organisations, so its message largely failed to resonate.

Ukraine’s challenge in effective global engagement is threefold. Firstly, for many countries, the Russia-Ukraine war is a distant one, far removed from their own regional priorities. Secondly, Russia has successfully exercised influence through diplomatic engagement of political elites at events such as the Russia-Africa summit, and by blaming grain and fertiliser shortages on Western sanctions.

Finally, Ukraine’s global diplomatic engagement has been limited since independence, leaving the country in a weak position to challenge Russia’s narratives. The country lacks diplomatic representation, intelligence capacity and foreign policy expertise to tell its story effectively to a wider global audience.

Participating in regional summits and opening new embassies, as Ukraine is doing now, are good initial steps, demonstrating commitment to a wider global engagement. However, the country needs a vision for its engagement beyond the war.

To formulate and implement this vision, Ukraine must understand regional geopolitics and methods of diplomatic engagement across the Global South. Its approach must be rooted in the differentiated national and regional priorities, such as access to digital technologies, tackling climate change, or food security. Failure to do so risks missing a window of opportunity to build relations with new countries.

Moving forward with reconstruction

While the outcome of the Russia-Ukraine war is yet to be determined, as is the shape of post-war security arrangements, Ukraine is already rebuilding damaged infrastructure and working to secure financing for reconstruction. As Ukraine and its partners gather in London to discuss the reconstruction of the country, geopolitical risks loom large. How these risks are managed will shape the country’s reconstruction and determine its role in the shifting geopolitical landscape.