Concerns grow as rich countries continue to fall short of their climate finance commitments, running the risk of derailing international climate negotiations. The UK must finally pay its fair share of climate and adaptation finance.

The UK is still not paying its fair share of climate and adaptation finance.

In a Ministerial Statement made on 17th October 2023, the UK government unveiled its plan to deliver £11.6 billion in international climate finance (ICF) from 2021-22 to 2025-26. The announcement follows months of sustained pressure from civil society after it emerged that the government was considering dropping its international climate finance pledge. This led to widespread calls for the UK to commit and demonstrate how it planned to deliver on these pledges. While we welcome this renewed commitment, it still falls short of the country's fair share by around $5.88 billion.

The global community is at a critical juncture as the clock continues ticking on climate change. The annual conference of parties (COP) remains a key platform to advance climate ambition. Yet, as the world gears up for COP28, tensions are mounting, fuelled by rich countries’ continuous failure to deliver on their climate finance commitments. This crisis runs the risk of not only jeopardising the outcome of COP28, but of placing the world’s most vulnerable populations at even greater risk.

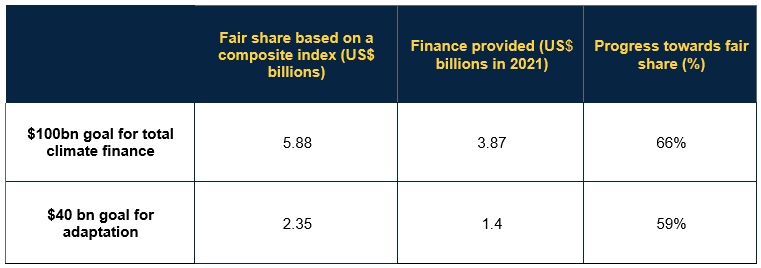

At the 15th Conference of Parties in 2009, developed countries promised to ramp up climate finance to $100 billion a year by 2020. But by 2021, rich countries were still yet to reach this target. As one of Europe’s largest economies and as a member of the Champions Group on Adaptation Finance, the UK should take a leading role for international climate and adaptation finance flows. Rishi Sunak agrees, as noted in his statement at COP27 reaffirming that “central to all our efforts is honouring our promises on climate finance.” Yet, according to ODI and the Zurich Flood Resilience Alliance’s latest report A Fair Share of Climate Finance? The Adaptation Edition, in 2021 the UK was still not meeting its fair share of climate and adaptation finance. Not only did it not deliver on its promise, the UK also has one of the largest gaps between its fair share and the climate finance it actually delivered. In 2021, the UK provided $3.87 billion in climate finance, representing only 66% of its fair share. Furthermore, it provided $1.4 billion for adaptation finance, only amounting to 59% of its fair share. Vulnerable countries and communities bearing the brunt of the climate crisis deserve better from the UK.

The UK’s new ICF plan falls significantly short of global needs

Like many other developed countries, the UK urgently needs to fulfill its international commitments. Critical financial resources are essential to support the most vulnerable countries and communities, who are already grappling with the severe impacts of the climate crisis including droughts, floods and heatwaves. Moreover, it is worth reiterating that the $100 billion goal was meant as a floor for climate finance provision rather than a ceiling, as needs amount to an estimated $4 trillion by 2030 to keep a 1.5C trajectory. It is essential for the UK’s climate finance commitment to align with its historical responsibility and capability to address the crisis. Climate change does not affect everyone equally and lower-income economies and communities face the worst impacts. Justice requires that nations most responsible for the crisis step up their responsibilities.

The new climate finance strategy relies on a significant change to what ‘counts’ towards the £11.6 billion ICF goal

The UK should be leading by example with equitable and sufficient climate finance contributions. However, recent statements indicate that the UK is seeking to meet its commitment by expanding the range of spending it classifies as ICF to include payments into development banks and additional money for businesses. Changing the rules around ICF accounting is worrying, and goes directly against the country’s long-held position that the standards of what counts as climate finance should be raised.

One significant change in the UK’s ICF goals is the inclusion of climate-related contributions to the World Bank and other multilateral development banks (estimated at an additional £200m a year). In addition, the majority of the £11.6 billion is due to be provided in the final two years, which will create an unachievable demand on official development assistance as well as reducing other important expenditure. This decision severely undermines the country’s standards and reputation on ICF accounting, and risks further eroding the already fragile trust between developed and developing countries.

Another shift is the loosening of restrictions around how much of the UK’s investment through British International Investment (BII) can be classified as climate finance, resulting in more finance flowing to the private sector rather than the kind of climate change initiatives countries need. At least 30% of Official Development Assistance (ODA) invested in BII will now be counted as climate finance. But BII may not be a suitable vehicle for climate finance, as a recent Select Committee report noted. The report heavily criticised BII for its lack of alignment with development goals, exposure to fossil fuels, and an overuse of loans in the disbursement of its funding. Critically, only a fraction of BII investment goes towards adaptation. With increasing proportions of ICF flowing through BII, the UK’s ability to deliver funding for adaptation - and for that funding to go directly to local actors and communities as well as to fragile and conflict affected countries - could be undermined. It is critical for ICF to be provided as grants for these priorities. Loans can cause unsustainable debt levels, which reduces the fiscal space countries have to address climate-related emergencies, to bolster resilience against future disasters, and to allocate funds to other vital areas such as education, healthcare, development and adaptation. With COP28 around the corner, backtracking on a strong record of predominantly using grant finance for ICF tarnishes the UK’s reputation and will further fuel tensions around the negotiating table.

The UK must not turn its back on communities on the frontlines of climate change

The UK’s failure to provide adequate funding and its complicity in driving down international standards on climate finance threaten to do irreparable damage to its credibility. More importantly, it is leaving vulnerable communities and countries without the support they need to become more resilient to a changing climate.

Only by finally paying their fair share of climate and adaptation finance in a transparent, just and equitable way can the UK – as well as other developed countries that are similarly underperforming – protect both its own reputation and the credibility of the international climate finance process as a whole.

-

A Fair Share of Climate Finance

Read more about A Fair Share of Climate Finance.