British International Investment (BII), founded in 1948, is celebrating its 75th anniversary this month. BII (formerly known as CDC) has undergone significant changes over the past 25 years.

At least four debates will be crucial in shaping BII’s future activities: (i) increasing investment volumes that go beyond the market and have a development impact; (ii) making appropriate choices regarding sectors, instruments and geographies; (iii) mobilising finance without getting distracted by mobilisation targets; and (iv) finding its evolving role in supporting development strategies, such as sustainable industrial development in the poorest countries.

A period of significant change since 1999

The period since 1999, when the new CDC act was introduced, has been a turbulent one for BII. It started with a stable period of steadily increasing capital flows to the poorest countries, followed by a sudden stop in financial flows during the global financial crises of 2008-2009. More recently, there have been periods of macroeconomic crises brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic, the Russia-Ukraine war, global inflation, and climate change. During this period, its shareholders (formerly the Department for International Development (DfID), now the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO)) considered privatising it (but fortunately did not), changed the instruments at its deposal (moving from direct loans and equity to equity in funds, and then back to a greater emphasis on direct loans and equity), and shifted from no additional public capital injections between 1999 and 2015 to significant capital injections in each of the last eight years. CDC/BII itself has risen out of the shadows from a ‘mere’ private equity investor and has become a prominent player in development.

My work at ODI as an analyst, researcher and advisor to the UK government, UK Parliament, CDC, and other DFIs has mirrored this evolution. I have analysed its relevance (addressing market failures and why subsidies are used, its role in promoting UK investment, and the business case for capital injections). I have also examined its focus on instruments compared to other DFIs, its transition from an opportunistic investor to a development player, and exploring its macro-level impacts. BII has increased its investment volumes, and its staff has grown 20 times, from around 25 staff members in the early 2000s to over 500 now. It has also increased its climate finance and gender-focused investments and is increasingly involved in global development debates. While there is much to celebrate, there are four areas that would benefit from further debate, decisions and actions.

Question 1: How can BII step up its investment volumes?

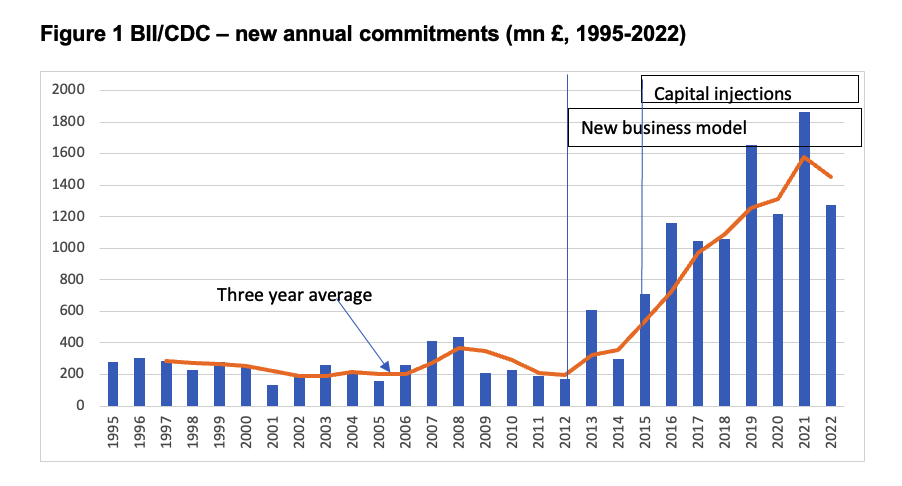

Development impact is determined by the combination of investment volume and the average impact of each investment. Investment volumes were subdued until 2012 when CDC began to use a new business model following interventions by then DFID Minister, Andrew Mitchell (see evidence to the IDC Parliamentary Enquiry where he argued that “CDC had lost sight of its original development mission.”). By 2016, Priti Patel, a DFID minister at the time, began advocating in Parliament for a large capital injection based on evidence from ODI regarding development impact.

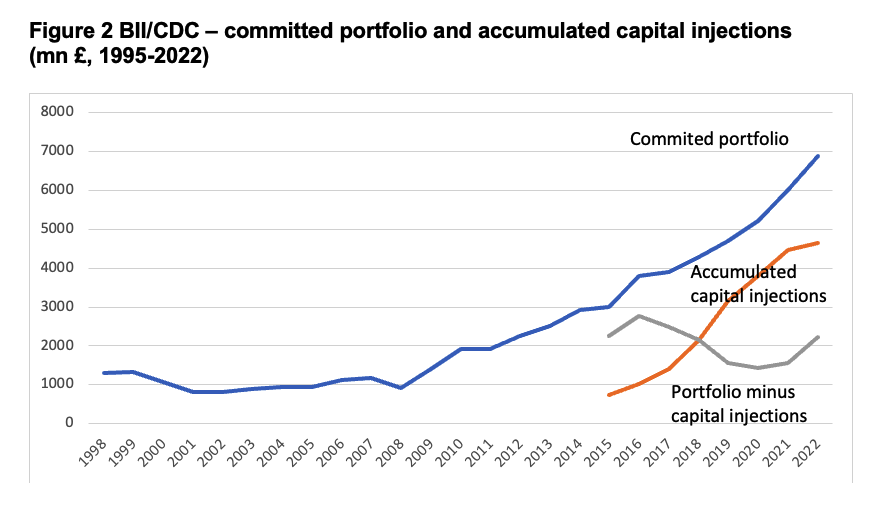

By the end of 2022, BII had an invested portfolio worth £7 billion, up from $816 million in 2001. It has made £11 billion in new investments over the past decade. BII increased its annual commitments (Figure 1) from £320 million per year (2007-2014) to £1,250 million per year (2015-2022), while capital injections from DFID reached £580 million per year over the same period. Interestingly, excluding accumulated capital injections, BII’s committed portfolio has not increased (Figure 2) over the past eight years (whilst it did in the decade before that). Whilst these have been exceptionally volatile years (and BII have not been sufficiently countercyclical after e.g. the global financial crisis), we could have expected a larger step up and, given the positive annual capital injections, we should have seen an increase in new commitments rather than a decline in 2022. This could reflect the fact that returns from a larger portfolio have yet to materialise whilst capital injections decreased in that year.

A fundamental question for the next five to ten years is how BII can achieve higher volumes of investment while maintaining or improving the development impact for each unit of investment. What changes does BII need to make, and what complementary actions are required from others?. Some BII staff members have suggested using balance sheet optimisation and adopting a more commercial bank-like approach (e.g. FMO) to achieve scale, while others may dismiss this idea as it could limit BII’s ability to operate as a pioneer. Also, the more BII is following (rather than being additional to) the market, the more pro-cyclical it becomes.

Question 2: How can BII continue to prioritise sectors, instruments and geographies that are most relevant to the needs of the poorest?

Strategies change, mandates evolve, and new instruments have been added to BII’s toolkit. BII has been asked to focus on different sectors and countries over time. There is now a real challenge that BII could increasingly target large climate finance loans in Asia, where it is a small part of a large investment community, at the expense of equity investments that support job creation in more challenging African environments (where BII has a more unique and additional role to play but often in time-consuming smaller deals). Both causes are important, and the issue here is not the size of projects but the real trade-offs at the country and sector levels. This involves allocating time and staffing resources to appropriate objectives, as explained by BII’s Managing Director, Colin Buckley.

Current analysis from ODI suggests that DFIs invest relatively little in fragile states or in agricultural value chains. DFIs may have an interest in investing more in food security in fragile contexts but fail to capitalise on the opportunities (with the notable exception of a few investments) because of political and security challenges, unrealistic requirements with respect to standards, expected returns or available staff time. A new narrative on risks and returns needs to be agreed upon between BII and its shareholders.

Question 3: How can BII not be distracted by the demand for financial mobilisation but focus on enhancing its core investments and support for gross fixed capital formation?

There is significant emphasis on using mobilisation ratios, which (for economists) can be meaningless descriptions when discussing DFI investments. Shareholders often impose several objectives on DFIs, such as the need to invest in the SDGs whilst earning a financial return and being additional to the market. However, they are also seeking to move DFIs towards where the market is already investing, i.e. by mobilising private finance. These conflicting objectives create inherent tensions that are not discussed here. Yet the demand for DFIs to mobilise finance with the reporting of leverage ratios as ‘proof’ of such mobilisation, is dangerously affecting the core business of DFIs, which should be additional to the market (and in a countercyclical way) whilst investing in profitable businesses that help promote development goals.

The use of leverage ratios is misleading for several reasons. A specific leverage ratio is neither inherently good nor bad, without additional information. A 5% or 95% stake in a fund or company can mean DFI finance is catalysing or being catalysed by, private finance flows. Without knowing the context, the direction of causation is unknown. DFIs should not be targeting finance as an outcome sought, but rather development impacts which depend on whether and how such finance is translated into capital formation at the country level, and how a country uses such capital. This is not measured by (static or dynamic) financial mobilisation at deal closure. The real question remains how DFIs can promote additional investment in projects with high development impact (which may or may not involve, more or less, private finance) and this is measured in the long run by economic variables such as the national accounts or household consumption surveys.

Question 4: How can BII find a more active and targeted place in supporting development strategies?

Although BII’s strategy for 2017-2022 had an ambitious goal of transforming entire sectors, this has not really been put into practice systematically. BII could collaborate more with other DFIs and, importantly, with other stakeholders, such as government actors. We have argued the case here around job creation and economic transformation and here for country-level development goals. Achieving this will require significant changes in the years to come. BII will need to collaborate more closely with local policymakers, as successful investment projects depend not only on access to finance but also on effective complementary policies and institutions.

BII’s strategy for 2022- 2026 focusing on productive, sustainable, and inclusive development is promising. For example, it now considers not only the backward linkages of its investments but also its role as an economic enabler and catalysing marker. This has the potential to lead to impacts on productivity or structural transformation. However, DFIs can do more through more targeted and coordinated action around the investment at the country level, which is a proven pathway towards economic transformation. For example, there is significant political momentum in Africa behind the Africa Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) and industrial development, and its implementation could be supported more fully at the country level. There is also much attention to climate change mitigation and adaptation, such as green industrial policy in high-income and large middle-income countries, and BII could support sustainable industrial development to avoid a "green squeeze" in low and vulnerable middle-income countries. BII is well on its way from being an opportunistic private equity investor to becoming a strategic development partner.

**Note: the author would like to thank Andy Herscowitz, Hans Peter Lankes and Paddy Carter for their comments, although are not responsible for the contents of this blog.