The UK government recently published its long-awaited international development strategy. This strategy constitutes a further shift in the positioning of UK development policy. Building on last year’s integrated review, development is framed as one arm of a combined UK foreign policy approach vying for global influence against certain ‘malign actors’ (think China and Russia). While UK interests are at the front and centre of the document, concerns around the current constraints to development are consigned to the background.

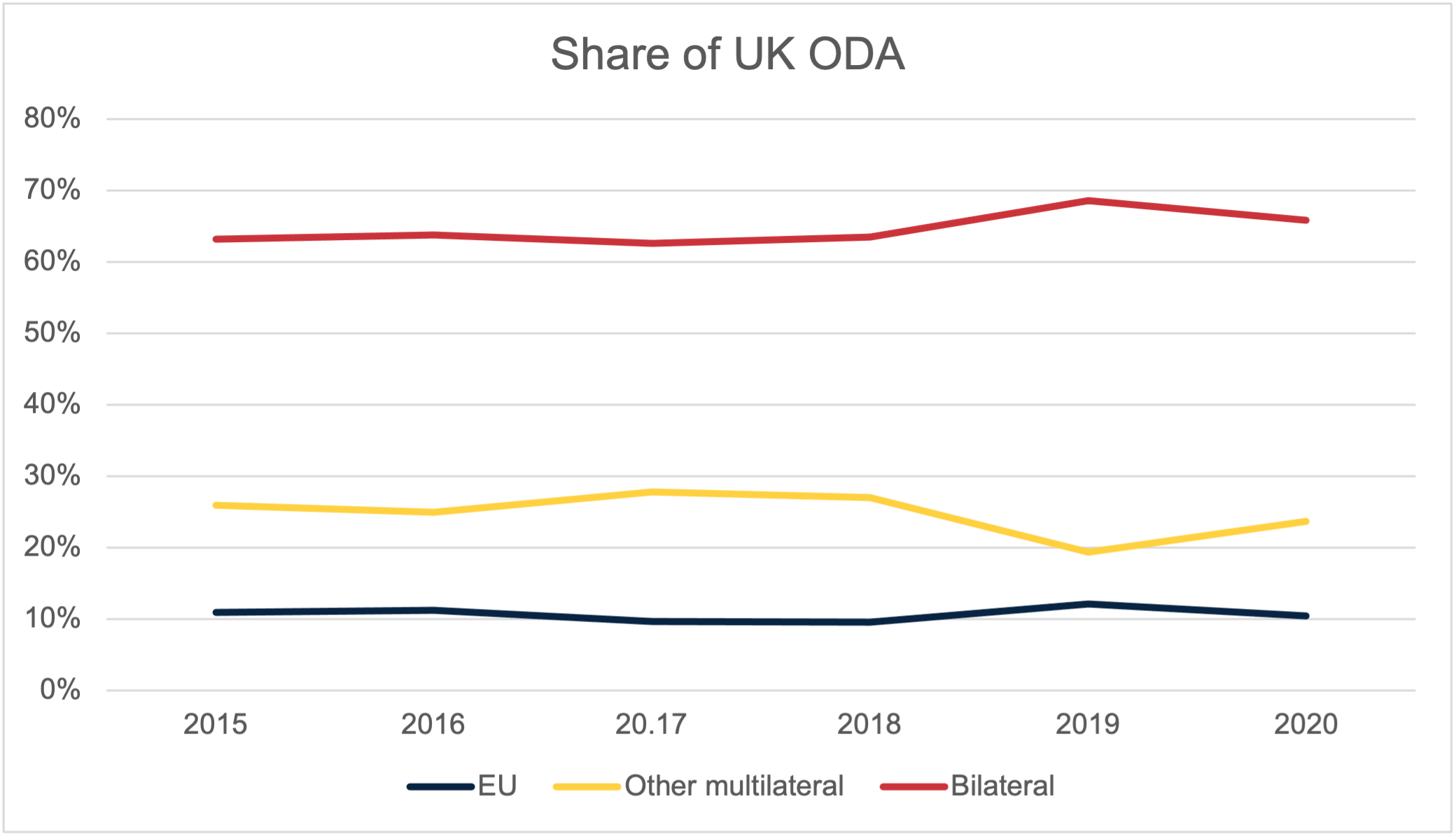

The extent to which the new strategy will usher in a similarly radical break in the day-to-day implementation of UK development policy is more of an open question. Stated priorities of trade and investment, humanitarianism, education (with a focus on women and girls), climate change and global health are a continuation of long-standing concerns. Much has also been written about the commitment to ‘take more control’ over UK Official Development Assistance (ODA) through directing financial assistance via bilateral channels, but even this evolution will arise largely as a result of leaving the EU. As Chart 1 shows, since 2015 the UK has channelled approximately one-quarter of its aid through the multilateral system when the EU is excluded.

Chart 1: Share of UK ODA channelled through multilateral and bilateral channels, 2015–2020

Source: UK Statistics on International Development

Nevertheless, both the strategy and last year’s spending review do indicate some notable shifts in emphasis for UK development policy that will likely pose significant implementation challenges for the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO).

1: Coping with the continued squeeze on FCDO resource budgets

On the face of it, the worst of the cuts to UK development spending now appear to be in the past. As the UK economy recovers from the pandemic, the FCDO’s overall budget is expected to rise due to the UK’s commitment to allocate 0.5% of its gross national income towards ODA.

This headline increase notwithstanding, the FCDO’s budget for resource expenditure will come under serious pressure (see Table 1). By 2024/25, the FCDO’s overall resource spending is expected to be lower than in the most recent financial year. The resource budget funds grants that go towards the FCDO’s day-to-day expenditure in sectors including health, education and humanitarian aid. Although the ‘freeing up’ of resources as a result of reduced contributions to the EU will ease the pressure somewhat, there will also be growing demands on the resource budget owing to the climate finance target (see below) as well as the current wave of humanitarian crises.

Table 1: Breakdown of FCDO budget, 2019/20 – 2024/25

| 2019/20 | 2020/21 | 2021/22 | 2022/23 | 2023/24 | 2024/25 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resource expenditure | 10.4 | 9.7 | 7.9 | 8.5 | 7.9 | 7.8 |

| Capital expenditure | 2.2 | 2.8 | 2.4 | 2.8 | 3.5 | 4.0 |

| (of which financial transactions) | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.9 | 0.4 | 0.9 | 1.2 |

| Total FCDO budget | 12.6 | 12.5 | 10.3 | 11.3 | 11.4 | 11.8 |

Source: Author’s own from 2021 Spending Review, updated FCDO 2022/23 budget estimates

2: Scaling up bilateral capital investment

In contrast to the resource budget, the FCDO’s capital spending is set to increase dramatically from £2.2 billion before the pandemic to £4 billion by the end of the spending review period. Within the capital budget, we can also see projections for ‘financial transactions’ rising – these relate to FCDO investments where future repayment is expected.

The focus on capital spending is consistent with the strategy’s stated emphasis on trade and investment. It might also reflect the Treasury’s continued preference for minimising the fiscal impact of the UK’s ODA commitment, since capital spending does not count towards the UK’s day-to-day expenditure. Where the FCDO provides loans or investments that are ultimately repaid, the government’s overall borrowing requirements are reduced.

While there will be intense competition for the resource budget, the FCDO may find it challenging to fully exhaust the proposed increase in capital budgets. Historically, a large proportion of FCDO capital spending has been channelled through the World Bank’s International Development Association (it comprised around 36% of total capital spending in 2021/22). However, at the most recent replenishment round the UK committed £1.4 billion for the period from 2022 to 2025. When compared with the £3 billion pledged at the 19th replenishment round, this represents a major reduction.

A significant part of the increase in capital spending could conceivably be absorbed by channelling more resources through UK development finance institutions including British Investment International (formerly CDC) and the Private Infrastructure Development Group. These organisations are oriented towards mobilising private investment.

It is also likely that ambassadors, particularly in middle-income countries, will see their capital budgets increase. An Indian infrastructure loan fund is indicative of an approach to bilateral country investment programmes that will be replicated elsewhere. Here, the UK channels relatively small volumes of funding through the Indian Development Finance Corporation, which on-lends resources to various private investors.

However, there are limits to the role played by the private sector in infrastructure expansion. Certain types of infrastructure – e.g. energy transmission networks – do not generate future revenue streams for private investors. For this reason, the strategy states that the UK will provide more direct bilateral support to sovereigns for infrastructure finance.

Unlike other G7 nations such as France, Germany and Japan, the UK does not have a development bank with established experience in lending to sovereigns. The FCDO also has limited experience in infrastructure relative to other sectors. The strategy highlights a ‘new innovative programme’ renamed British Support for Infrastructure Projects. Worth £500 million, the programme will be overseen by a managing agent and used to capitalise sovereign infrastructure loans. This remains relatively uncharted territory for the FCDO.

3: Meeting the UK’s international climate finance commitments

The new strategy also maintains the UK’s commitment to double its international climate finance target over the next five-year period, even while the volume of ODA is relatively smaller (see Table 2). This will create pressure to ‘rebadge’ aid in certain sectors.

Another way the UK will look to increase climate finance is through making greater use of loans, guarantees and other blended finance instruments. Accounting rules in climate finance capture the face value of ‘mobilised’ financial flows rather than their grant equivalent. In changing the mix of financing instruments, the UK can increase the volume of climate finance without necessarily increasing the overall fiscal burden.

The UK will also be looking to find ways to maximise the climate finance component of its multilateral aid contributions. Unlike other donors, the UK does not report its core contributions to multilateral development banks as part of its climate finance target. Whereas the banks allocate a greater share of their overall portfolio to climate finance, the volume of UK climate finance does not increase. As such, the UK may favour dedicated climate finance trust funds or specific international climate funds.

Table 2: Average UK ODA and international climate finance targets

| 2015–2020 | 2021–2025 | |

|---|---|---|

| Average annual UK ODA commitments | £14.3bn | £12.1bn |

| Average annual UK climate finance commitments | £1.2bn | £2.3bn |

Source: UK International Development Statistics and 2021 Spending Review (assuming that the UK maintains its ODA target at 0.5% of GNI until 2025)

4: Reducing bureaucracy (but with fewer bureaucrats)

The strategy places a major emphasis on ‘stripping back bureaucracy’ and giving ‘greater autonomy to our Ambassadors and High Commissioners’. FCDO staff and partners may not immediately feel the benefits of lighter bureaucracy given concurrent efforts to reduce 20% of the overall headcount in the FCDO. At the same time, there will be an increase in the relative volume of resources over which the FCDO will have control and oversight. This comes on top of the continued administrative challenges in merging two departments. Where resources are thinly stretched, the FCDO will inevitably require greater implementation support from consultants and partner organisations.

5: The continued shadow of uncertainty

The new strategy points to the benefits of a ‘patient approach’ to development. The FCDO’s ability to provide this level of support will depend on a policy environment that allows for long-term planning. However, such an environment has been anything but stable over the past five years. Since 2016, there have been seven different ministers in charge of the UK’s development portfolio, each with his or her own views on UK development priorities. The recent merger between the Foreign and Commonwealth Office and the Department for International Development only adds to the sense of inconstancy.

Most importantly of all, the volatility of resources since the pandemic has made medium-term planning near-impossible for the FCDO. The FCDO currently works on the assumption that the ‘fiscal situation’ will not allow for a reversion back to the 0.7% ODA commitment. However, the possibility of a sudden jump in ODA may very well create contingency planning headaches for FCDO staff.

If the new development strategy ushers in a period of greater certainty, then this might be its most pivotal contribution to improving the impact of UK development policy.

This insight piece benefitted from the comments of Annalisa Prizzon and Nilima Gulrajani on a previous draft.