Welcome to the third edition of ODI's Hot Take on all things climate! In September, we explored wealthy nations' failure to reach the $100 billion climate finance target in 2021 and what lies ahead, how to better align climate and development objectives, and what the Global Stocktake might achieve for climate action.

What will follow the $100 billion climate finance goal?

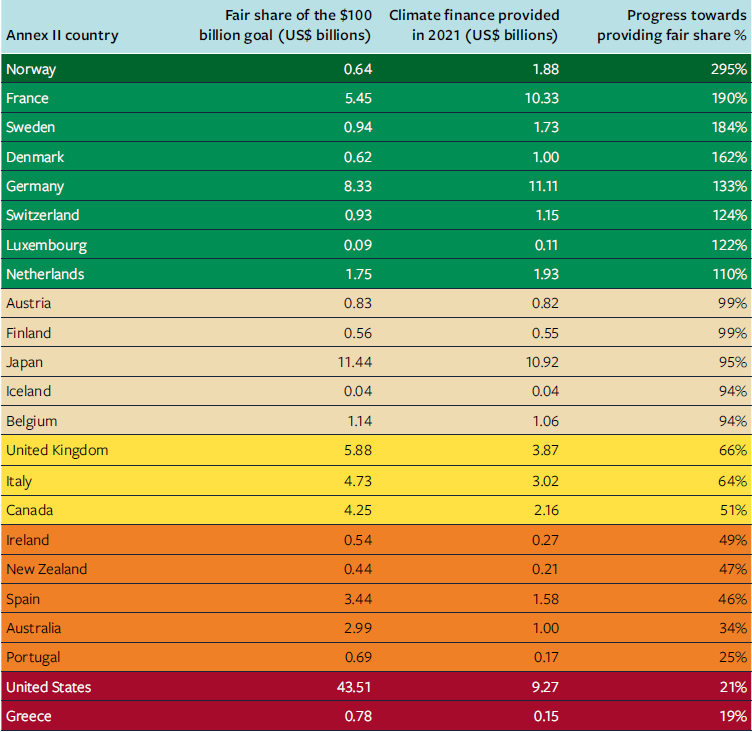

2021 marked yet another year in which ‘developed countries’ (as defined by the UN climate accords) have fallen short of their commitment to provide $100 billion of climate finance per year to developing countries. But the collective nature of the climate finance goal shields those developed countries who are not paying their ‘fair share’. So which countries are most responsible for the climate finance gap?

In a bid to strengthen accountability, ODI and the Zurich Flood Resilience Alliance publish an annual report assessing each developed country’s progress towards paying their ‘fair share’ of the $100 billion target. This analysis is based on each country’s historic responsibility for greenhouse gas emissions, gross national income, and population size.

The USA remains overwhelmingly responsible for the failure to reach the $100 billion target, falling short of its fair share by $34 billion. With shortfalls of around $2 billion each, Australia, Spain, Canada, and the United Kingdom are also among the worst performers in absolute terms.

After the COP26 commitment to double adaptation financing, this year, ODI also assessed adaptation finance ‘fair shares’. The good news is that developed countries are on track to double adaptation finance from 2019 levels to $40 billion by 2024. However, this does not mean all countries are providing their fair share of adaptation finance. The USA once again falls short - but the gap is likely to be filled by northern European donors.

The lack of accountability among developed countries is just one of the weaknesses of the $100 billion goal. Another is that the indistinct language failed to take into account the needs of low and middle-income countries.

Negotiators hope to correct this in the successor to the $100 billion commitment. Starting in 2025, the New Collective Quantified Goal (NCQG) is intended to better incorporate the needs of low- and middle-income countries. But these are diverse, dynamic, and difficult to capture in specific financial terms or treaty language.

In July of this year, ODI published six options for effectively embedding needs with the NCQG. These range from adopting new frameworks for assessing developing country needs, to setting quantitative sub-goals for different kinds of finance (for example, public and private, concessional and commercial), to promoting innovative programmatic approaches, like Just Energy Transition Partnerships.

Whatever format the NCQG ultimately takes, accountability and transparency must be at its heart. For far too long, a lack of accountability in the delivery of climate finance has plagued climate negotiations and damaged trust. International solidarity and sustained cooperation demand that all developed countries pay their fair share of a climate finance goal. That goal must be delicately designed to meet the needs and priorities of developing countries as they transition to a low-emission, climate-resilient economy.

Climate versus development: an unhelpful debate.

The world’s major powers are now in a ‘green race’.

China dominates the manufacture of solar panels, wind turbines, and electric vehicles. Europe has introduced a border carbon adjustment mechanism, extending its carbon price to foreign suppliers. The USA has adopted the Inflation Reduction Act, which commits an estimated $370 billion to stimulate and re-shore green manufacturing. These efforts are transforming global supply chains.

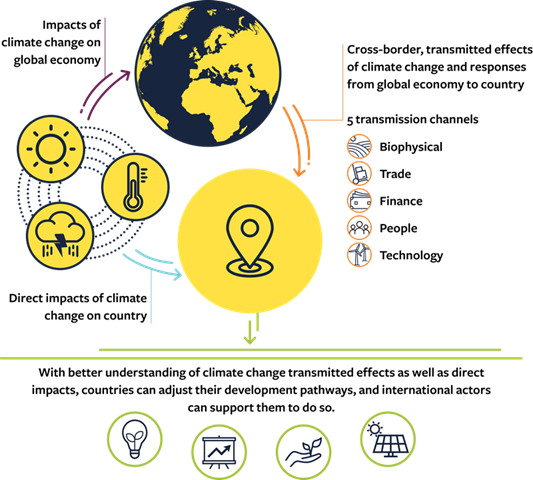

Physical hazards, like more frequent and severe storms, wildfires, and droughts may be the most visible manifestation of climate change, but the policies put in place to cut emissions and adapt to rising temperatures will also create profound changes across borders. The USA, the EU and China are all effectively capitalising on net-zero goals to catalyse a green industrial revolution at home – with significant implications for countries whose development strategy rests upon serving these vast markets.

In a new report, ODI offers a framework for understanding how national development opportunities will be re-shaped by climate change impacts and policies. In addition to changing trade patterns driven by green industrial policies, we identify four other transmission channels: biophysical effects, finance, people, and technology.

Our analysis challenges the persistent narrative that countries need to choose between investing in development and climate change mitigation. Governments now need to anticipate how markets and policies will change due to climate change in order to position themselves to compete in a lower-carbon economy.

Preparations are well underway in some countries. Indonesia, for example, plans to harness its huge nickel reserves to win a place in emerging electric vehicle value chains. Malaysia and Viet Nam are establishing themselves as major exporters of solar products.

But decarbonisation in the major powers risks kicking away the ladder to development. Green compliance requirements developed by Western institutions may prevent lower-income countries from entering these lucrative markets or accessing their capital. Few countries can match the massive Chinese or American subsidies for green technology, which means they cannot attract foreign direct investment to nurture these emerging industries.

In simple terms, the major powers are largely offering national solutions to global problems. Just as the impacts of climate change flow across borders, so too should the policy response.

A greater understanding of how the impacts of - and our policy response to - climate change can affect development pathways will begin to unlock the kinds of synergies we need. The US Inflation Reduction Act and the EU’s carbon border adjustment mechanism have already commanded the attention of trade policymakers.

But there has been less attention to the transmission channels identified in our report. On financial flows, for example, climate-smart financial regulation in the major financial centres need to be accompanied by capacity building of finance professionals in emerging economies. Otherwise central bankers are simply shutting off the supply of climate finance to where it is most needed.

On the movement of people, immigration policy could be joined up to climate policy to fill critical skills gaps. The decarbonisation of buildings or agriculture, for example, will be very labour-intensive, offering an opportunity to better integrate migrants into the local economy.

There are no easy solutions to align the climate and development agendas together. But only emphasising the tensions between them simply justifies climate inaction, and will ultimately threaten development everywhere.

The Global Stocktake and our chance to recalibrate

In less than two months, the first Global Stocktake (GST) of the Paris Agreement will conclude in Dubai. The 2-year process, which will take place every five years going forward, is intended to assess our collective progress on climate action since the Agreement was signed in 2015. Countries are expected to then use the GST findings to refine their Nationally Determined Contributions and accelerate climate action.

Unsurprisingly, the GST confirms that the world currently falls short. The Paris Agreement sets a goal of limiting warming to “well below 2°C”, and we are currently on track for a rise of between 2.6°C and 2.9°C at the end of this century.

But the GST also offers some success stories. Take clean energy technologies: the last decade alone has seen costs fall by 55% for wind energy and nearly 90% for solar and lithium-ion batteries. In fact, such is the decline in cost of clean electricity that the International Energy Agency have predicted oil use to peak by the end of this decade.

But critically, the world is far behind in aligning finance flows with climate goals. The last decade has been littered with a series of failed finance commitments and technocratic dialogues that have lost sight of the consequences of inaction. As a result, only $850 billion a year is channeled to mitigation and adaptation. We need at least $4 trillion to meet our goals.

ODI co-chairs the Finance Working Group (FWG) of the Independent Global Stocktake (iGST) – a network of civil society organisations working together to support the Global Stocktake; encouraging countries to capitalize on its outcomes.

The iGST has made a submission to the UNFCCC on what the GST should prioritise going forward. The recommendations include enhancing the use of concessional and risk-taking capital to reduce the cost of commercial investment in climate solutions; rapidly securing a consensus on debt restructuring – or in some cases, debt relief – and; setting out a timebound roadmap for reforming the financial system to raise and direct the capital needed for a low-carbon, climate-resilient transition. These are only a few of the many areas where the GST could catalyze impactful action.

The GST has the power to communicate not just what the necessary next steps are, but who should take them and by when. Under the UAE Presidency, it should clearly convey the responsibilities of the myriad financial actors necessary to unlock resources for climate action at scale. Finance ministries, central bankers, multilateral development banks, commercial banks, institutional investors, corporations, and more have a role to play in simplifying and expediting access to climate finance in a way that is driven by local needs and expertise.

The GST creates an opportunity to reflect on and redress the financial failings to date – should countries choose to seize it. All eyes on COP28.