The 26th UN climate change conference, COP26, is taking place later this year. It is the first real test of the Paris Agreement, and thus of our collective ability to respond to the climate crisis. COP26 marks a pivotal moment because the Paris Agreement includes a ‘ratchet mechanism’, whereby its signatories are expected to pledge more ambitious emission reduction targets every five years (this first milestone was delayed by a year due to the pandemic).

In the last two years, many of the world’s largest economies have pledged to reach net-zero emissions by mid-century. Few climate observers would have forecast such a rapid escalation of ambition in the immediate aftermath of the Paris Agreement. However, stronger near-term targets are crucial because greenhouse gases accumulate in the atmosphere: early reductions in emissions make it easier to achieve long-term temperature goals. Those following climate debates therefore heaved a sigh of relief in April, when national leaders announced a host of 2030 commitments. Among the G7, these included:

- The European Union pledged to curb emissions by at least 55%, compared to 1990 levels.

- Canada pledged to reduce emissions by 40–45%, compared with 2005 levels.

- Japan pledged to reduce emissions by 46%, compared with 2013 levels.

- The United States pledged to at least halve greenhouse gas emissions, compared with 2005 levels.

For context, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change found that emissions would need to nearly halve by 2030, compared to 2010 levels, to have a 50% chance of limiting global warming to no more than 1.5°C at the end of the century.

Recent announcements bring the projected average temperature increase to 2.4°C above pre-industrial levels. This is an improvement, but falls short of the Paris Agreement’s target of well below 2°C and close to 1.5°C. There also remains a stark divide between most countries’ emissions targets and their policies. With current climate policies, the world is on track for an average global temperature increase of 2.9°C by the end of the century.

There are other tensions in the lead-up to COP26. In particular, there is much dispute how much climate finance has been mobilised. The climate goal agreed at the Copenhagen Summit in 2009 was $100 billion a year by 2020. The timing and nature of COP26 is also contested, with many countries calling for negotiations to be delayed or moved online given the unequal vaccine rollout.

The challenge

As the host of both summits, the UK government is using the G7 to build political momentum towards COP26. The G7 has long recognised the threat posed by global warming, announcing aspirations to stabilise carbon dioxide emissions as early as the 1979 summit in Tokyo – over a decade before the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) was born.

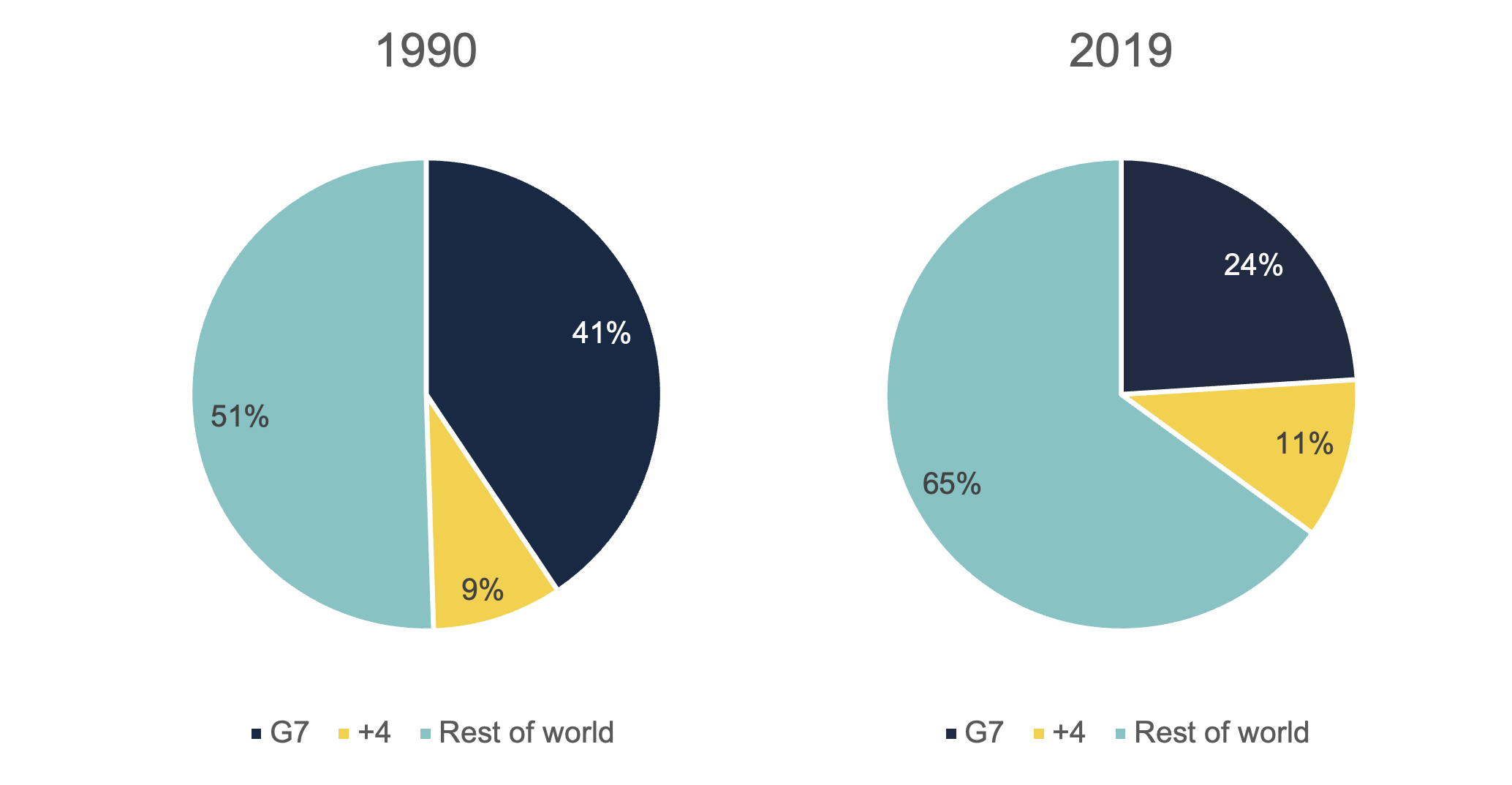

However, the G7 have become less significant players in terms of their share of global emissions. The G7 and the four countries invited to join it in 2021 – Australia, India, South Africa and South Korea – used to account for half of global emissions (see Figure 1). Now they account for much less, partially due to the rapid decarbonisation of the European members and partially due to rapidly increasing emissions from China and other emerging economies. At around 28% of global greenhouse gas emissions, China’s domestic response to climate change could be considered as significant as the collective domestic efforts of the G7.

Figure 1. Emissions from the G7, the four countries invited to join the 2021 G7 (Australia, India, South Africa and South Korea) and the rest of the world in 1990 and 2019.

The opportunity

Although their share of global emissions has fallen, the G7 members and their guests remain a powerful political force given their economic size and international standing. The G7 summit could therefore lay the groundwork for a successful COP26 in three key ways.

First, the G7 could end domestic public support for fossil fuels immediately.

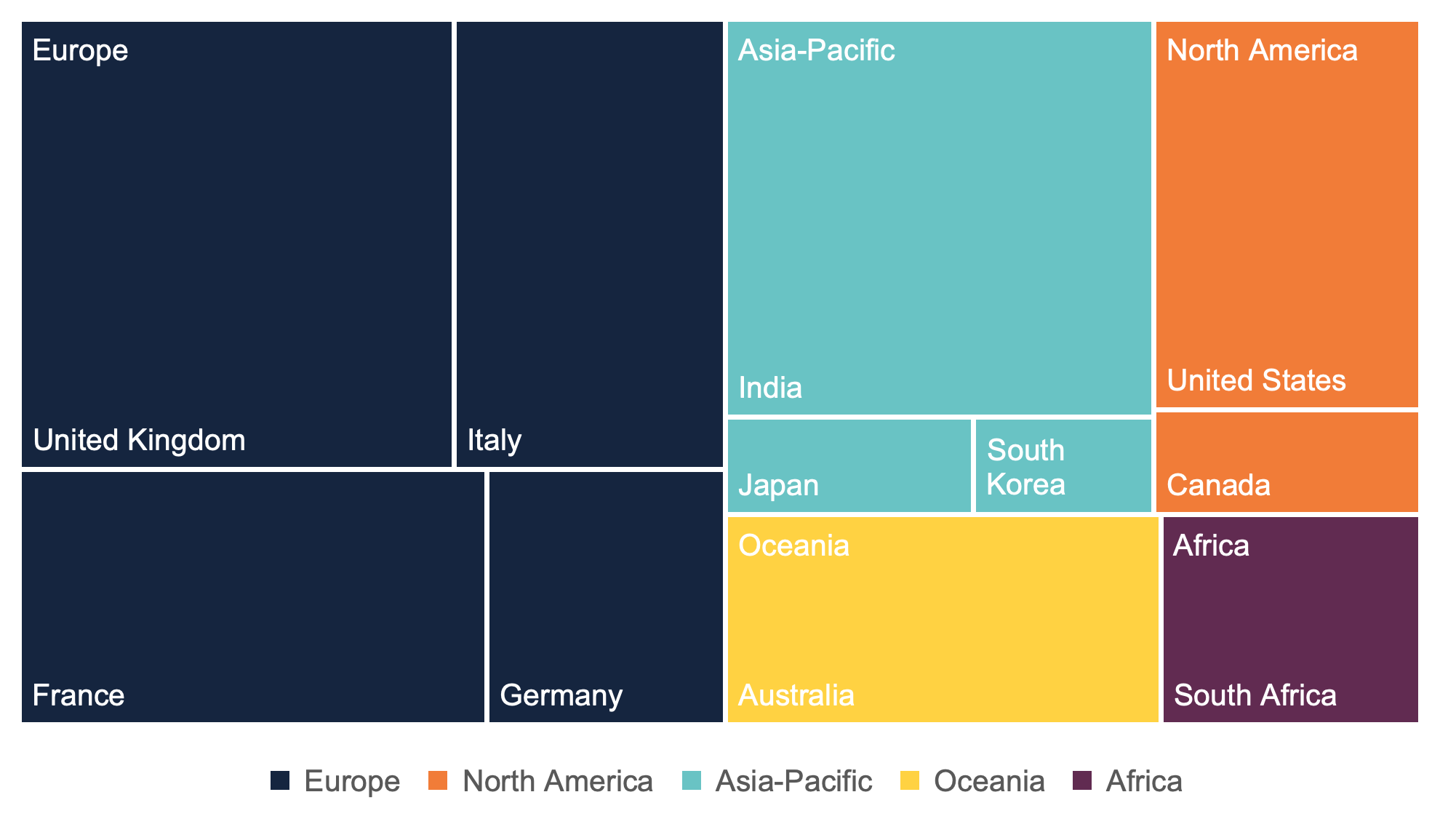

The G20 agreed to phase out support for fossils at the Pittsburgh Summit in 2009. A decade later, the G7 and its invitees collectively provided $77.8 billion in public support to domestic coal, oil and gas, including electricity generated from these fuels (see Figure 2). With a couple of exceptions where these resources were deployed to enable a just transition for workers and communities, these funds skewed prices to encourage fossil fuel consumption and production. Given the dual fiscal and climate crises, the G7 summit offers a chance for its attendees to end support for fossil fuels and invest in other urgent priorities such as healthcare, social protection and a clean energy transition.

Figure 2. Fossil fuel subsidies from the G7 and the four countries invited to join the 2021 G7 (Australia, India, South Africa and South Korea) in 2019.

Note: UK data in the Climate Transparency Report 2020 is from 2017, which was the latest data available at the time. In this graph, we use the more updated figure of USD 15.4 billion.

Fossil fuel subsidy reform is urgent not only because of climate concerns, but also because of pressure on public budgets. The pandemic also caused tax revenues to collapse even as public spending soared. Yet between January 2020 and March 2021, G7 nations committed more than $190 billion to support coal, oil and gas, while clean forms of energy received $147 billion.

These fiscal stimulus packages were mostly designed to meet the immediate needs of workers and businesses during lockdowns, but governments have also missed opportunities to enable a green economic recovery. For example, despite generous support for the airline and car industries ($115 billion), few countries have attached requirements for any climate targets or reductions in pollution (Tearfund et al., 2021). The G7 varied substantially in the scale and climate consistency of their fiscal stimulus. As of May 2021, Italy and the US had directed over 70% of their energy-related spending to support fossil fuels; Canada, France, Germany and Japan all had much greener recovery packages. Going forward, the G7 and its guests could announce a ‘do-no-harm’ principle for spending and investment, ensuring that any lingering support for fossil fuels is to enable a just low-carbon transition.

The G7 could go even further by collectively introducing mandatory climate-related financial disclosure. Private investors, lenders and insurers need much more information to price the risks and opportunities of climate change. France and the UK have announced that they will require companies to measure and disclose climate-related risks, and a recent Executive Order from the Biden administration suggests that the US will not only mandate disclosure of climate-related financial risks, but also explore new regulatory interventions. If other G7 members announced mandatory disclosure of climate-related financial risks at the summit, this would collectively drive a step change in the climate consistency of global investment and spending.

Second, the G7 could urge greater ambition among its guests.

On many global challenges, the G7 and the guest countries that the UK has invited may be a natural alliance of democratic countries with shared values. However, there is no such natural alliance on climate change.

The European members of the G7 have long been leaders on climate change mitigation. Germany and the UK in particular have achieved impressive emissions reductions, with annual greenhouse gases 36% and 44% below 1990 levels in 2019. Emissions from Japan have remained relatively constant over the same period, while emissions from Canada and the US have increased by a fifth and a third respectively. The G7 is therefore not a coalition of like-minded countries on climate change, but an uneasy assemblage of leaders and laggards.

Securing strong climate commitments at the G7 summit looked even more difficult with the participation of Australia, India, South Africa and South Korea. While these four countries may share the democratic credentials of the G7, they are also distinguished by their substantial support for coal and (with the exception of India) their highly insufficient NDCs.

Despite these inauspicious conditions, the virtual meeting of G7 Climate and Environment Ministers on 20–21 May demonstrated growing consensus and rising ambition on climate change. The Ministers’ Communiqué committed to set 2030 emission targets in line with limiting temperature increases to 1.5°C – a striking development given that many high-income countries had opposed the inclusion of this target in the Paris Agreement. The Climate and Environment Ministers also recognised that coal power generation must be urgently phased out, and made new announcements regarding decarbonising power systems, ending international support for coal and welcoming new multilateral efforts to support transitions away from coal.

These are huge strides forward. As the International Energy Agency’s long-awaited report lays out, a plausible pathway to net-zero by 2050 rests on an early phase-out of coal in advanced economies. Canada, France, Italy and the UK had previously pledged to phase out coal by 2030, while Germany has policies in place to reduce coal. Securing comparable commitments from Japan and the United States is a tremendous diplomatic achievement.

The G7 can now collectively turn their attention to its guests: Australia, India, South Africa and South Korea. The first three are large coal producers; Australia produces primarily for export, while India and South Africa consume most of their coal domestically. Coal remains the mainstay of electricity generation and is considered an important employer and source of tax revenue in all three countries. South Korea has been a significant international financier of coal-fired power, but earlier this year pledged to end these activities.

As a high-income and economically diversified country, Australia has the capabilities and resources necessary to govern a rapid, equitable energy transition. The G7’s commitment to phase out coal strengthens the incentives for decarbonisation, and the summit offers an opportunity to direct international attention to Australia’s poor climate record. By comparison, India and South Africa face greater transitional challenges, with weaker capabilities and fewer resources. The G7 could announce new support for just transitions in these countries.

Third, the G7 could provide the support necessary to secure a green economic recovery for low- and middle-income countries.

Formal deliberations will begin on the new climate finance goal at COP26. This new goal will succeed the target of $100 billion a year from 2020, agreed at COP15 in Copenhagen in 2009. The $100 billion target also serves as the annual floor for international climate finance prior to 2025, when the new goal will be adopted.

The $100 billion goal and its successor are about more than just money. Unlike development or humanitarian finance, climate finance is based on an explicit historic responsibility in addition to a moral imperative. Yet to meet the targets in the Paris Agreement, climate finance must also be used to drive the transition to low-carbon, climate-resilient economies and societies. Negotiations about the new climate finance goal therefore have the potential to either bridge or exacerbate divides that risk poisoning other elements of the climate negotiations.

Conversations about the new climate finance goal will not happen in a vacuum. Parties’ negotiating positions are informed by wider economic and social priorities – such as debt sustainability, economic competitiveness and geopolitical relations – as well as science-based targets. In particular, the devastating impacts of Covid-19 will profoundly shape deliberations on the new climate finance goal.

The G7 needs to be much more sensitive to this interplay to secure a successful outcome from COP26. The UK, for instance, raised eyebrows when it urged other members to arrive with a ‘substantial pile of cash’ for climate action even as it slashed development assistance. At a larger scale, decisions around special drawing rights and debt relief in the wake of Covid-19 will determine both the capacity and the appetite of low- and middle-income countries to pursue climate action. The G7 member countries will need to be generous and far-sighted across multiple fronts if they are to sustain trust in UNFCCC processes and maintain momentum behind the low-carbon transition. Commitments to this effect at the G7 summit would reassure developing countries as COP26 looms, particularly if the communiqué recognises the need to mobilise finance for adaptation and resilience, as well as mitigation.

The G7 need to highlight not only what its members will help to finance, but also what they will no longer finance. The G7 Climate and Environment Ministers have announced that they will end support for coal-fired power generation abroad, as has South Korea. That leaves China as the only significant international financier of coal. France, Germany and the UK have further announced an end to export finance for fossil fuels. Since the IEA’s new roadmap makes it clear that there is no room for new coal mines or oil and gas fields if we are to hold net-zero emissions by 2050, the G7 could collectively go further than ending support for coal: they could also pledge to end finance for oil and gas production, and to use their position as shareholders of the multilateral development banks to introduce the same provisions.

The G7 must take both climate and development imperatives into account. With their substantial fossil fuel reserves, huge infrastructure deficits and low per capita emissions, many low- and lower middle-income countries have understandably been exploring whether oil and gas could act as bridge fuels. Indeed, until recently the G7 members have been financing exploration and production in countries such as Mozambique, South Sudan and Tanzania. These economies will now have to forego the economic rents associated with fossil fuel extraction to mitigate a climate crisis that they didn’t cause.

Recognising the role that fossil fuels could otherwise play in financing development, the G7 should consider bolder and more innovative forms of assistance – such as paying low- and lower middle-income countries to keep their reserves in the ground. These financial flows should complement, rather than replace, financial assistance and technology transfer for the development of a secure, reliable and affordable supply of clean energy. If the G7 summit unlocks more generous, creative and climate-consistent international public finance, it will lay the foundations not only for a successful COP26 in Glasgow, but also a successful COP27 in Africa.