Progressia is a landlocked country in southern Africa, where traditional farming is the dominant way of life. The climate is semi-arid; the ecosystem is fragile.

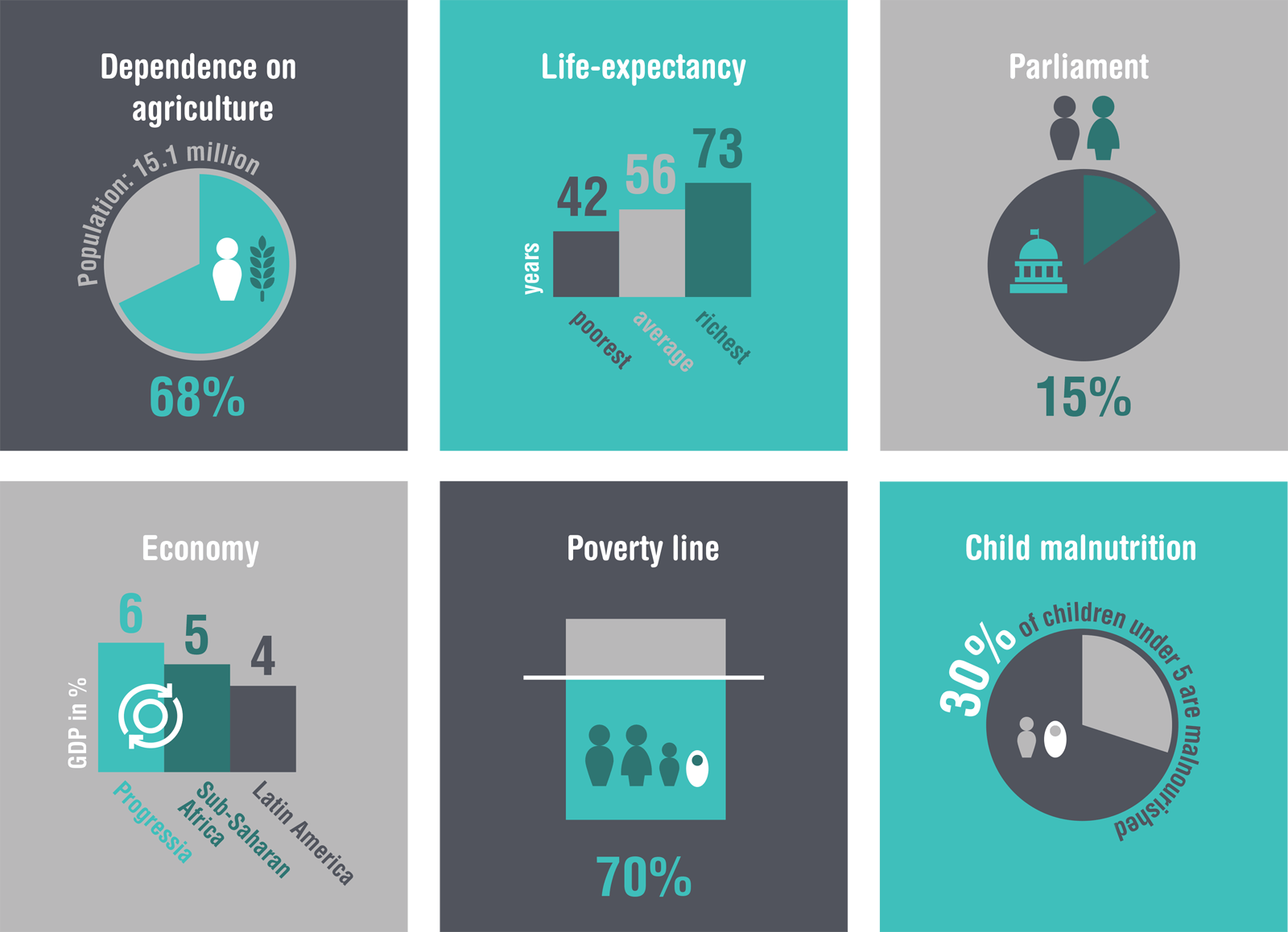

The majority of the 15.1 million population live below the poverty line. A small and powerful elite live very different lives in the cities.

Balancing development priorities

Progressia is fictional but typical of the region. More than one third of the world’s extreme poor live in sub-Saharan Africa: a large proportion of the people left behind despite the development progress of recent decades.

The Progressian government accepts the need to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals by 2030, but there is little agreement on how best to balance economic growth, environmental sustainability and social inclusion.

In these pages, and in the accompanying report, we use real-world research and analysis to look at a range of fictional trade-offs to be made as Progressia tries to find a path towards sustainable, equitable development.

Methodology

Progressia is a fictional country but the challenges and trade-offs it faces, as well as the development pathways it could adopt, are drawn from 49 case studies of progress from all over the world.

Frequently asked questions

Read more about the methodology

We selected a real-world context for Progressia: the savannah region of southern Africa. We created a narrative about Progressia that embodies the geography, climate, politics, and social and economic characteristics of southern Africa.

Following analysis of drivers of progress, the 'scenario-axes of uncertainty' technique was used as a structuring device. The technique combines perspectives on economic growth, inequality, social development and environmental sustainability.

The scenarios show how the future could unfold, based on how possible outcomes are (and could be) influenced by the ways in which key drivers of progress interact with each other in the scenario contexts. Two targets then became the axes of a two-by-two matrix which produces four scenarios.

Although Progressia is a fictional country, we use real-world examples, projected future trends, and general characteristics of southern Africa to frame the arguments.

The Progressians

Progressian society is divided. The mostly rural poor make up the vast majority of the population. They have benefited little from the economy’s 6% per annum growth in recent years.

The majority of the population live below the poverty line, subsisting on less than US$1.25 a day. Healthcare is scarce and expensive and malnutrition is common. There is increasing resentment and social unrest about economic and social inequality.

A small but wealthy upper-middle class live mostly in the cities; they typically have access to professional healthcare, quality education and secure, well-paid jobs.

Life expectancy of the poor majority is substantially lower than that of the wealthier elite.

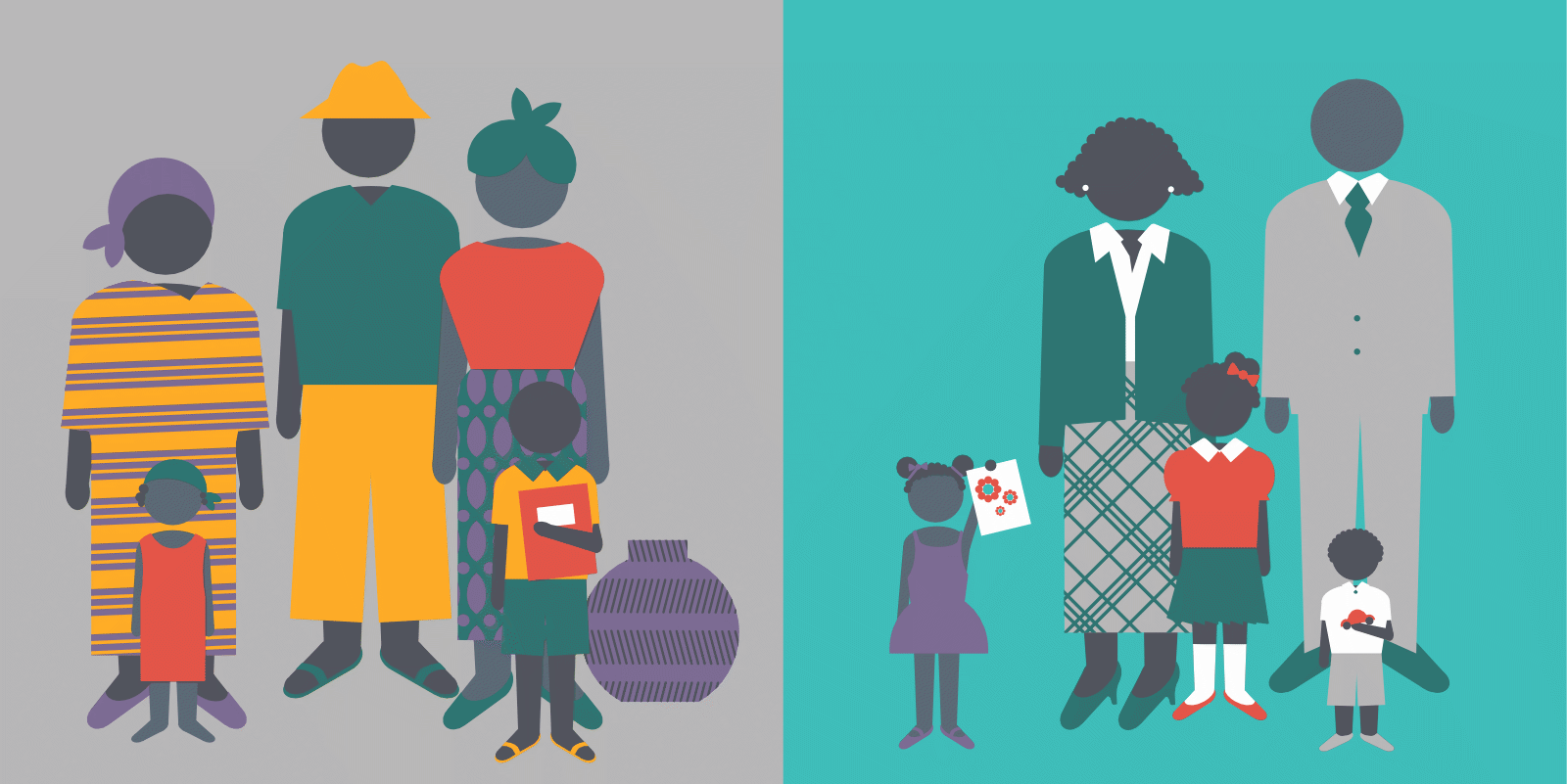

The Malunga and Chilembe families are representative of these two sections of Progressian society. The various policy paths that Progressia may travel down over the next 13 years will affect their lives. Follow these families to see how.

The Malunga family

The three generations of the Malunga family often don’t have enough to eat. They live in two mud huts and work in their field in a remote, rural part of the country, where the rains sometimes fail.

Leoni Malunga: aged 40, Leoni suffers from trachoma, a bacterial eye infection which has made her blind in one eye. She is a widow living with HIV, her husband having died of AIDS.

Leoni Malunga: aged 40, Leoni suffers from trachoma, a bacterial eye infection which has made her blind in one eye. She is a widow living with HIV, her husband having died of AIDS.

Tonderai Malunga: the son of Leoni, Tonderai is 24. He left school at 10 and has been working on the land since.

Tonderai Malunga: the son of Leoni, Tonderai is 24. He left school at 10 and has been working on the land since.

Patience Malunga: 22, Tonderai’s wife Patience didn’t finish primary school. Neither of her parents are alive. She enjoys making up stories for her children.

Patience Malunga: 22, Tonderai’s wife Patience didn’t finish primary school. Neither of her parents are alive. She enjoys making up stories for her children.

Stanley Malunga: 6 years old, Stanley recently started going to school. He also helps his parents in the field.

Stanley Malunga: 6 years old, Stanley recently started going to school. He also helps his parents in the field.

Lucia Malunga: 3 years old, Lucia spends a lot of the time at home with her grandmother.

Lucia Malunga: 3 years old, Lucia spends a lot of the time at home with her grandmother.

The Chilembe family

The Chilembe family live in a modern house in the capital city and take holidays abroad once a year. They have good career prospects and enough disposable income to live comfortably.

Pandora Chilembe: 30 years old, Pandora studied in Paris, has a degree in finance, and speaks English and French. She’s not currently working.

Pandora Chilembe: 30 years old, Pandora studied in Paris, has a degree in finance, and speaks English and French. She’s not currently working.

Hudson Chilembe: 31, Hudson works as a lawyer in the city.

Hudson Chilembe: 31, Hudson works as a lawyer in the city.

Kike Chilembe: 8, Kike goes to primary school and has a mixed group of friends, some of whose parents are diplomats and ex-pat bankers.

Kike Chilembe: 8, Kike goes to primary school and has a mixed group of friends, some of whose parents are diplomats and ex-pat bankers.

Orla Chilembe: 4 years old, Orla enjoys drawing and dancing and spends her time between her mother and her childminder.

Orla Chilembe: 4 years old, Orla enjoys drawing and dancing and spends her time between her mother and her childminder.

Ellis Chilembe: aged 2, Ellis has a few words and likes playing with his older sisters.

Ellis Chilembe: aged 2, Ellis has a few words and likes playing with his older sisters.

Development priorities

The economy of Progressia has grown healthily in recent years but the benefits of growth are concentrated in a small section of the population. The government is considering how best to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals by 2030. Several of the goals deal with three central themes: equality, economic growth, and environmental sustainability.

Equality

Reducing inequality is one of the biggest challenges for Progressia, where wealth is concentrated in a small part of society and recent economic growth has had little positive effect on the majority of people

Economy

Many of the Sustainable Development Goals relate to economic growth. To achieve their aims, the government of Progressia must create sustainable growth that benefits all parts of society.

Environment

Ecosystems are fragile and vulnerable to the ravages of climate change. It’s imperative for the quality of life of the population and the future prosperity of the country that development does not happen at the expense of environmental degradation.

Trade-offs

There are 17 Sustainable Development Goals. Finding policies that advance each of them, without any negative effects on the others, is a challenge. International development is often a compromise between people who, for various reasons, prioritise one issue over another.

In these pages, and in the accompanying report, we look at the potential trade-offs between equality, the economy and the environment, and the way in which policies can have both positive and negative knock-on effects.

Environment versus equality

How can Progressia combine agricultural and environmental policies to both reduce deforestation and tackle hunger?

How can it improve the livelihoods of those people who depend on the land for food production and income generation, while protecting the land for future generations?

Economy versus environment

How can Progressia build resilient infrastructure, promote industrialisation and foster innovation, while at the same time reducing carbon emissions?

How can policies bolster manufacturing and increase employment, while halting and reversing land degradation and the loss of biodiversity?

Equality versus economy

Is it possible to achieve sustained and strong economic growth in Progressia without widening the already significant gap between rich and poor?

How can growth increase access to education and public services, reduce unemployment and enhance wellbeing for all?

Recommendations

Future speculation about Progressia is an effective way to present a comprehensive view of the complex field of sustainable development and policy trade-offs, and it should be seen for what it is: a systematic way of pulling together considered projections about what might happen on the basis of experience, the Development Progress case studies and what we know are current policy dilemmas facing policy-makers – to pave the way for deeper investigation, rather than a complete set of tried and tested conclusions. We believe that this approach does little harm, and may have many benefits. The ability to make wise choices about trade-offs is one of the most important yet challenging skills for policy-makers.

Three key recommendations emerge from this case study:

1. Policy approaches should be holistic

Minimising trade-offs requires an approach that gives technical, institutional and international policy consistency. Making and sustaining improvements requires the recognition that there are compromises to be made between human welfare and environmental protection. For example, sometimes, protecting forests comes with a price for the poor: people are dispossessed of their livelihoods, homes and cultural ties.

Policy-makers should use Poverty and Social Impact Analysis to understand the costs and benefits of their choices, identifying inclusive reforms that leave no one behind.

2. Decision-making must be evidence-based

Policies that factor in environmental sustainability can be expensive, but can save money in the long-run and promote innovation. Policy-makers should consider the long-term costs and benefits of policies, drawing on a range of different forms of evidence, including the cost of inaction.

We recommend relevant and regular evidence-based analyses of the potential economic and environmental impacts of policy choices to support the decision-making process.

3. Focus on the bottom 40%

Policies that limit inequality make societies fairer and wealthier. Policy-makers need to focus on the bottom 40%. Poverty reduction alone will not be enough. Increasing access to education, training and healthcare creates greater equality of opportunities in the long run.

We recommend that governments prioritise job-related training and education for the low-skilled over their whole working lives. It is equally important to ensure that the labour market raises the income share of the poor and the middle class.