A new tool in the box

Next month, the International Monetary Fund (IMF)’s much-awaited Resilience and Sustainability Trust (RST) is expected to be operational. The new trust is being funded through $40 billion-worth of commitments from various G20 nations to channel Special Drawing Rights (SDRs) to the IMF. The IMF will in turn provide highly concessional long-term lending for up to 143 countries to support economic and financial ‘resilience’ in the face of climate and pandemic-related threats.

High-income countries channelling new funding to support lower-income countries for worthy causes – what is not to like? Quite a lot, according to civil society actors, who have been vocal in their criticisms of this new mechanism for channelling SDRs. In their view, the RST is:

- too restrictive, in terms of tight income thresholds for eligibility;

- too burdensome, in that countries must adopt a standard IMF programme to access it;

- too uncoordinated, as its management does not involve other development banks; and

- too miserly, in terms of the amount of cash available and the interest rate charged.

However, the challenges do not stop there. The RST gives the IMF a new role: setting what is effectively budget support-style policy conditionality for climate and pandemic resilience. This creates new – and difficult – dynamics between the IMF and its client countries. The RST is therefore a step into the unknown as it both expands and blurs the limits of IMF policy conditions.

So why develop this new and potentially risky instrument? How will it work? And what can be done to best manage it?

In the beginning was the SDR

The RST needs to be seen as the result of a political compromise. First of all, the governments of G20 countries have come under pressure to be seen to be ‘doing more’ to counter the effects of the Covid-19 crisis. The acute impact of Covid-19 and its continued economic repercussions have led to low-income and vulnerable countries calling for additional hard currency to cope with a global shock over which they had limited control.

While G20 countries have been keen to demonstrate willing, there has been a reluctance to pay for it in terms of new fiscal commitments, where volumes of aid have remained largely unchanged. Last August’s $650 billion issuance of SDRs helped to square this circle: it created additional hard currency reserves of particular value to countries vulnerable to balance of payments crises. However, the vast majority of SDRs were deposited in the central banks of the wealthiest countries that had least need for them. The G20 therefore committed to voluntarily contribute $100 billion of ‘excess’ SDR reserves to more vulnerable countries.

The value of these voluntary contributions was tempered by concerns of creditor countries, with their central banks insisting that SDRs retain their ‘reserve-like asset status’. These banks sought guarantees that they could recall SDR contributions should they need them (in the instance of a major macroeconomic crisis, for example).

This requirement immediately established the IMF as the front-runner for managing any redeployment of SDRs. This is because it is more straightforward for the IMF to provide creditors with this assurance compared with other institutions (like multilateral development banks). The IMF is already responsible for the overall global handling of SDR issuances and exchanges. It also has an existing track record of on-lending SDRs and providing creditors with assurances that they can withdraw their money through its Poverty Reduction and Growth Trust.

Complicating matters further, creditor countries have been seemingly unwilling to countenance reallocating SDRs simply because some countries have been worse affected by global economic shocks than others. Instead, the insistence has been that loans be linked to ‘global public goods’ – in other words, things from which they might also benefit, directly or indirectly.

The IMF has therefore been tasked with designing a mechanism that can link its operations with global public goods concerns, while reassuring creditors that they can get their monies back. The RST – and the long-term loans it can provide in exchange for certain prescribed policy reforms – is the result.

The unenviable task of designing new lending conditions

IMF staff and their government counterparts now find themselves with the challenge of agreeing lending conditions that are ostensibly related to ‘global public goods’. In this respect, the IMF Board Paper states that ‘RST loans would initially support measures addressing climate change and enhancing pandemic preparedness given their global public good nature; other challenges could be added over time.’

The RST documentation has already put forward some sample lending conditions related to climate change that programme countries might expect to follow. They broadly fall into two groups:

- Institutional reforms focused on integrating climate concerns into financial planning and policy-making processes;

- Specific fiscal and financial policy measures designed to mitigate the impact of climate change, while also improving a country’s balance of payments position.

The task of designing conditions carries four risks:

1. Expert overreach – government reforms plans based around IMF expertise

While none of the climate-related conditionalities listed above are obviously wrong, there is evidently a strong bias towards reform measures that are closely related to traditional IMF areas of expertise. Financing strategies, public investment management, public financial management: this is all familiar terrain for the IMF. While finance and financial reforms obviously matter for resilience and sustainability, it is not the case that they are the measures that matter most. Should a government prioritise investment in a pandemic-preparedness budget code? Or in improving genomic sequencing?

This matters because institutional reforms are not without their costs and IMF conditions can influence overall government reform agendas. There is a danger that governments prioritise measures based on what the IMF happens to be good at, rather than a solid analysis of the most pressing vulnerabilities.

2. Too much from too few – overburdening central finance and planning agencies

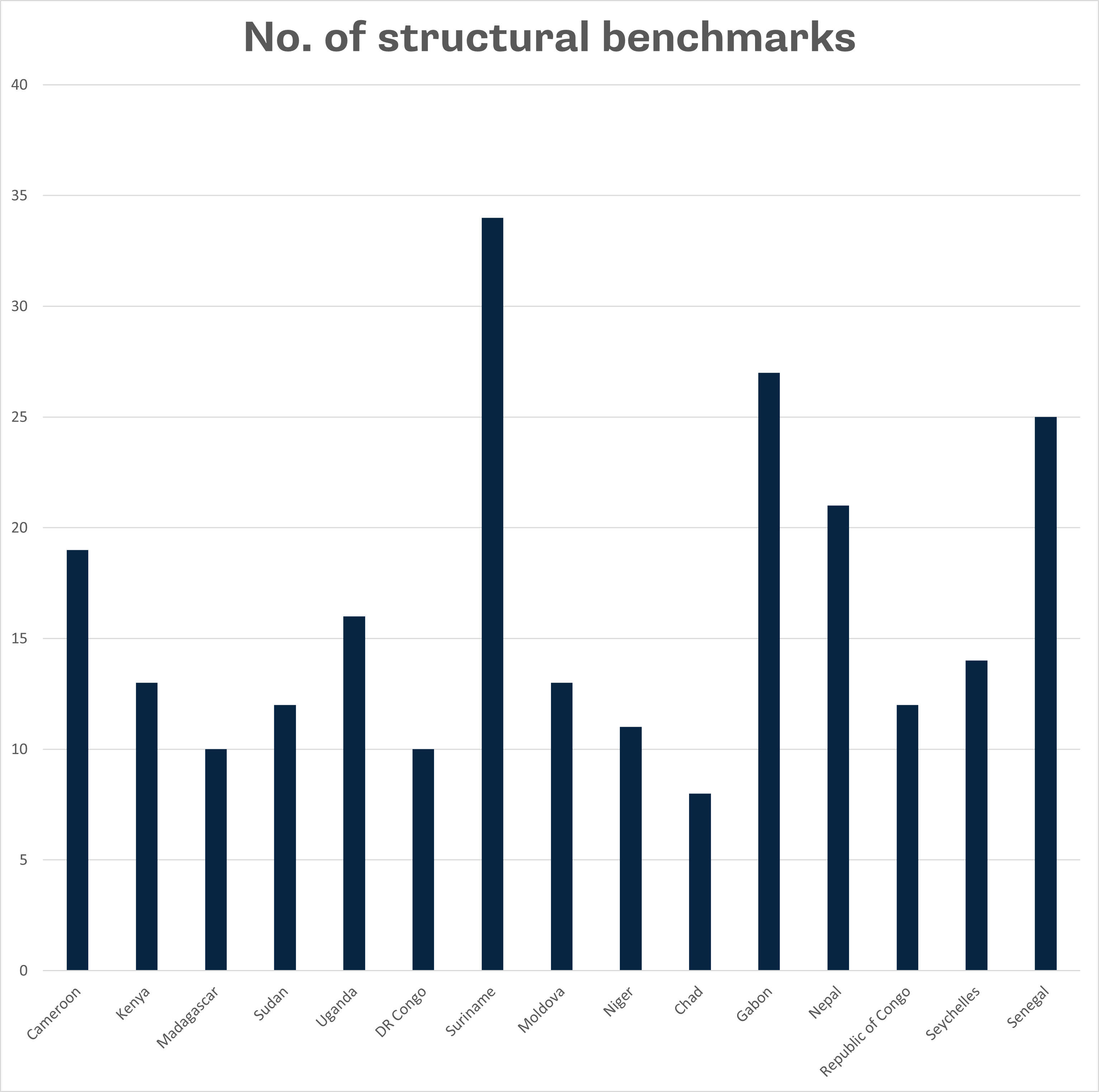

Reforms do not happen in isolation, and someone needs to actually implement them. The proposed RST measures will mostly need to be executed by the same central finance and planning agencies that serve as the main counterparts to IMF surveillance and capacity-building work. Chart 1 shows the number of conditions that have already been agreed through 2021 conditionality programmes. RST conditions will be additional to this.

As a result, for many countries the same small group of civil servants working in the same key ministries will now be asked to implement simultaneous economic, fiscal, financial and budget policy reform at a time of economic crisis. There is a clear risk that such reforms could actually hinder state capabilities by adding to the kind of ‘premature load bearing’ or isomorphic mimicry that undermines real institutional reform.

The Seychelles provides an example. Over the next three years, 14 structural conditions have been agreed with the IMF and a further 16 with the World Bank through its Fiscal Sustainability and Climate Resilience Development Policy loan. If the Seychelles wishes to access funding from the RST, it will have to commit to addressing further climate and pandemic resilience reforms. This is a tall order for a country of 100,000 people. Will the additional measures support resilience, or prevent people from doing their day job?

3. The wood is the trees – visible reforms are not necessarily the most important ones

The RST approach implicitly assumes that there is a distinction between public policy reforms that support climate and pandemic resilience and other good public policy reforms. In practice, this is a difficult – if not false – distinction. Resilient states are those with effective public policy processes across the board. Such states can mobilise money, people and equipment to deal with a range of crises, because their public policy processes are well-developed. Opening up the public policy machine to strengthen those sub-circuits that are ‘climate-related’ and ‘pandemic-related’ while ignoring the rest is conceptually difficult and arguably counter-productive.

This can be seen in many of the sample institutional reform conditions listed in the Board Paper. These are effectively ‘climate add-ons’ to processes that (should) already exist. If these processes are working well, adding a climate element will certainly help them do better. If they are not working well – not inconceivable in the countries most likely to access RST finance – then adding a ‘climate dimension’ could lead to nothing more than a box-ticking exercise, with reams of additional published guidance but little substantive impact.

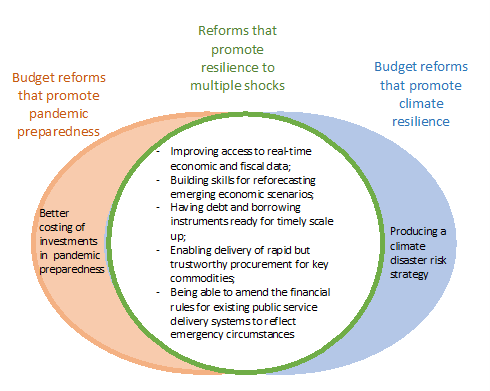

Figure 1 illustrates various fiscal management reforms that could conceivably promote resilience. There is a danger that the RST selects reforms based on whether they can be visibly linked to the specific challenges of climate and pandemics, while neglecting potentially more useful reforms that can strengthen government capabilities more generally.

4. Do as I say, not as I do – the credibility risk in stoking confrontational climate politics

Adding a more explicit climate dimension to the IMF’s conditionality threatens to raise the heat on complex issues of international and intergenerational equity. An institution that must be seen to be neutral and technocratic (at least to some degree) could therefore be dragged into some politically-charged debates.

The developed countries that have contributed the most to climate change are aiming for net-zero emissions targets or similar by 2050 or later. For them, climate mitigation is an ongoing policy agenda for which the costs will be paid over the medium- to long-term. In contrast, for RST borrowers, many of these costs must be paid right now through policy conditionality.

More controversially, all the resilience and preparedness reforms in the world will not prevent some countries – notably small island states – from suffering periodic natural disasters, nor will they push back rising sea levels. Implying that countries need to be a bit more ‘resilient’ in these circumstances risks blaming the victim.

This will be particularly galling if the governments of high-income countries start scoring their contributions to the RST as ‘climate finance’. Sceptics might start to question who is really benefiting from these tough and controversial climate-related conditions. In the most cynical view, RST donors could be accused of simply using the excess reserves generated through the SDR issuance to hit their international climate finance commitments and avoid the real fiscal cost of providing upfront grants rather than SDR-backed loans.

What can the IMF do?

Supporting climate and pandemic resilience – however defined – is a worthy goal, and the IMF now has $40 billion in loans to promote it. However, it has been handed something of a poisoned chalice with which to implement this system. How much does it want to drink? There are several options for a remodelled RST: some could be pursued jointly, while others would require a more fundamental rethink of the current structure.

1. Acknowledge limits and recognise these challenges up front

The limits of IMF expertise in this area should be acknowledged. It should be made clear that they are not experts on climate change or pandemics. Their most relevant experience is thinking in broad terms about what qualities make governments resilient to macro-fiscal shocks. Expectations that RST-based policy conditionality will markedly change overall country resilience to specific pandemic and climate shocks should be toned down to a realistic level. In designing policy conditions, the IMF should interpret resilience and state capability broadly. The IMF should recognise that there are multiple ways to achieve this and could usefully spell out their assumed ‘theory of change’ in doing so.

The IMF should also be much more vocal about what can realistically be done to manage climate and pandemic risks through the design of country-specific conditions. Needless to say, climate change and unexpected pandemics are global issues that no individual country can realistically solve alone. The IMF should be clear about the global systemic issues that contribute to country vulnerability. It should deploy research and evidence to make the point that RST countries are not typically the countries that undermine the sustainability of the global commons.

2. A strong all-rounder – use the RST to build states that are resilient to multiple shocks

During the Covid-19 crisis, many of the most critical capabilities for dealing with the impact of the pandemic related to broader-based qualities of public administrations. As shown in Figure 1, for finance ministries, these included having access to real-time data and appropriate debt instruments; being agile in forecasting and procurement; and adapting rules to reflect emergency circumstances. These are useful instruments for responding to many kinds of shocks, and all of them are to some degree the responsibility of finance and/or planning ministries.

If the IMF wants to impose climate and pandemic resilience conditions, it should work in these areas of financial and economic management capability that already have a demonstrable relationship to concepts of ‘resilience’, and which clearly fall within its mandate. This may result in a list of conditionality reforms that are similar to its existing set of standard policy and institutional reforms, but ‘sticking to what you know’ might make sense for a reform agenda that aims to build resilience across the whole of government.

3. Less is more – maintaining policy conditionality at a minimum

The IMF should be parsimonious in selecting policy conditionalities relating to the RST. More measures do not necessarily mean more of a good thing. Indeed, the IMF itself has broadly recognised this point through its commitment to reducing and streamlining conditionality throughout its programmes. If the IMF intends to encourage governments to undertake significant new activity to deliver climate or pandemic-related resilience reforms, they should also provide advice on what governments should be doing less of to compensate.

4. Keeping the peace – avoid tying the most controversial mitigation actions to the RST

Climate change mitigation is perhaps the most controversial area of policy reform. Asking lower-income countries to impose new climate taxes and/or remove popular-but-polluting subsidies can be justified where they relate to immediate-term fiscal sustainability. They are significantly more difficult to justify when demanded by an institution controlled by the higher-income countries that have contributed most to climate change. In the wrong light, this makes tough love look more like a punishment beating.

To avoid this, the IMF should only tie strict RST climate mitigation conditions to a policy that a recipient government has already planned. Governments can therefore use the IMF’s conditionality to strengthen their hand in tackling (likely unpopular) policy reforms they have already committed to, while avoiding the legitimacy-draining effect of being forced to undertake policy reforms that appear to be imposed from outside. This will go a long way to preventing acrimonious disagreement about the international and intergenerational equity of the RST, and the IMF’s role in implementing it.

Proceed with caution

In practice, the reputational and relationship risks facing the IMF as a result of the conditionality, policy focus and change in mandate inherent in RST may not matter much. The RST is only available to IMF programme countries, and most countries will move heaven and earth to avoid becoming one. For those countries on an IMF programme, the volume of funds available through the RST will only be a partial restorative to the immediate macro-fiscal problems that they and the IMF are trying to fix. Therefore, while the policy goals of the RST are certainly laudable, their actual impact may be more limited. This may save the IMF from many awkward conditionality conversations.

In entering the world of climate and pandemic resilience conditionality, however, the IMF is stepping well outside its comfort zone. This could be just the beginning. The move opens up a range of relationship risks that could have lasting implications for the IMF’s reputation and its working practices with client countries. This matters, as the world needs a ‘lender of last resort’ that is perceived by its creditors and borrowers to be (at least minimally) expert, neutral and fair. Some challenges could be overcome through a more careful design of the RST and its evidence base. Others are hardwired into the concept itself. The IMF should proceed with great caution as it involves itself in the business of supervising the behaviour of countries outside its usual home turf.