Introduction

Aid planners and observers deride departmental silos in donor bureaucracies as hopelessly out of fashion, ill-suited to multi-sectoral global challenges like a changing climate or a pandemic-induced recession. Nevertheless, Development Assistance Committee (DAC) governments continue to consolidate bureaucratic power for global development within their foreign affairs departments, in many cases sidelining more robust engagements by line ministries.

Tackling global challenges effectively needs donors to rethink how the resources and expertise of diverse governmental actors are brought together. Bilateral donor governance urgently needs a conductor to coordinate a whole-of-government development policy and an orchestra of actors for its implementation. Sadly, several donors are muddling through without either.

The growing dispersion of aid

Bureaucratic pluralism in development is the distribution of governmental authority for global development across diverse administrative entities. Using a new dataset that compiles government department spending of Official Development Assistance (ODA), we map three measures of engagement by non-primary government departments (hereafter ‘other government departments' or (OGDs)):

- the share of ODA channelled through OGDs beyond the primary department

- the number of OGDs used across donors

- the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI), a measure of the overall concentration of ODA through OGDs, where a score of 1 indicates that all spending was allocated through a single department (and thus highly focused in its intergovernmental allocations).

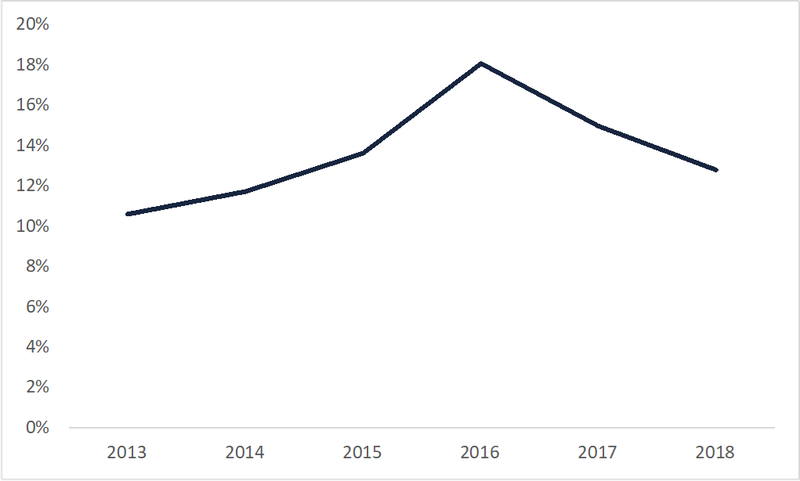

These measures provide insight into the overall trend in the use of OGDs, diversity in range of OGDs used, and changes to the concentration of funding allocated through OGDs, over time. Broadly, we see the growth of bureaucratic pluralism across all 29 bilateral DAC members for 2013–2018. The average share of ODA through OGDs increased among DAC donors from 11% in 2013 to 18% in 2016, dipping to around 13% in 2018 (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Percentage of ODA allocated through OGDs, DAC donor average 2013–2018

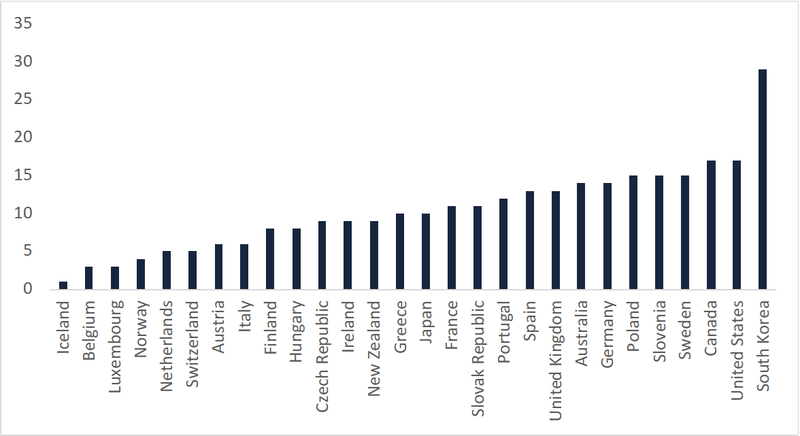

In 2018, donors used an average of 10 OGDs, with South Korea using the highest number of bureaucratic channels to disburse its ODA (Figure 2). In 2013, the average HHI score across providers was 0.55, declining slightly to 0.50 in 2018, suggesting increased bureaucratic pluralism in ODA spending over time.

Figure 2: Number of OGDs involved in ODA allocation in 2018, by donor

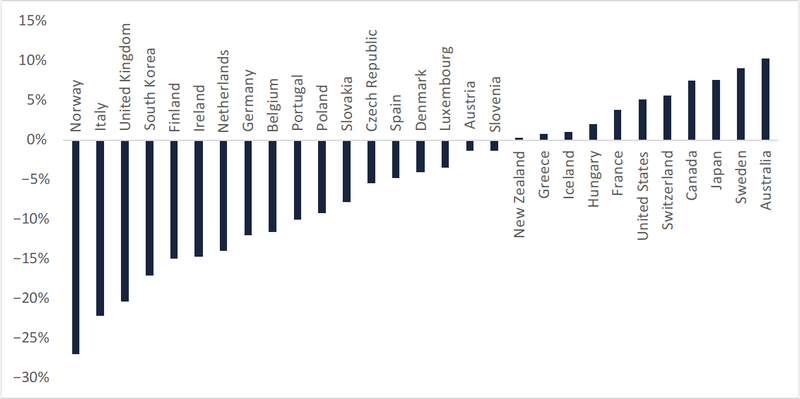

Our analysis shows that since 2013, 18 providers have seen growth in bureaucratic pluralism as aid concentration falls in key ministries (see Figure 3). The largest declines in the HHI over time were found in Norway, Italy and the United Kingdom. In the Norwegian case, the reduced concentration is largely driven by an increased share of ODA through the Ministry for Climate and Environment, which is responsible for allocating climate-related ODA as part of Norway’s International Forest and Climate Initiative. For Italy, the increase is largely attributable to spending via the Ministry of Interior, which is responsible for ODA funding associated with refugee hosting, while the increase in the UK is related to increased spending across OGDs as part of the 2015 aid strategy that sought to administer ODA beyond the Department for International Development (DFID).

Figure 3: Change in HHI values between 2013–2018, per provider

Mergers as mechanisms of bureaucratic consolidation

Increasing bureaucratic pluralism stands in contrast to consolidation that has occurred in several countries through – and following – recent mergers. In the last decade, standalone development ministries in Canada, Australia and the UK have been folded into their foreign affairs departments. Currently, no DAC country organises its development programme under the auspices of a standalone development ministry that unifies policy formulation and implementation. While often justified by the desire for coherence, impact and efficiency, the record of development mergers actually achieving these is mixed.

Instead, we see the growing power of foreign ministries to control a greater share of ODA resources. Canada and Australia achieved greater concentration in their ODA allocations after their 2013 mergers (Figure 3), even though these figures mask somewhat different trends. In Australia, deep budget cuts following the merger likely contributed to the increased concentration, with Australian ODA allocated via six fewer departments in 2020–21 than in 2013–14. In Canada, slightly increased concentration occurs alongside an increase in the number of OGDs used to allocate ODA spending (up by eight between 2013–14 and 2019–20), suggesting that while more ODA is allocated via Global Affairs Canada, small amounts of ODA are being distributed across more public actors.

In the decade leading up to the 2020 UK merger, the UK's share of ODA allocated beyond its primary department increased from 12.5% in 2010 to 26.3% in 2020, while it expanded the number of bureaucratic channels for its spending by seven over the same period. This dispersion was justified in the 2015 aid strategy by citing the demands of ‘a changing world’ and the need for ‘complementary skills’. Nevertheless, a ring-fenced ODA budget may have also elevated pressures to disburse aid more widely across government departments where heavy cuts were being inflicted. Provisional 2020 figures for UK aid indicate the volume of ODA channelled through departments other than the Foreign and Commonwealth Office and the Department for International Development grew from 22.4% in 2019 to 26.3%, with the largest increases to the Home Office (£151 million), Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) (£59 million) and the Export Credits Guarantee Department (£44 million). Nevertheless, post-merger there is some indication that the 2021 ODA budget will be delivered through fewer channels, with no projected allocations to the Department for International Trade, and large declines in flows through BEIS (−£313 million), Conflict Stability and Security Fund (−£198 million), and the Home Office (−£127 million) alongside declining ODA. The April announcement that the 2021/2022 departmental allocation will keep 80% of total UK ODA resources within the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) suggests a fall of 6.3 percentage points in the share of development spend through other departments compared to last year. Like Canada and Australia before it, the UK is showing post-merger signs of an inward pull of ODA resources towards its integrated foreign ministry.

Global challenges and the imperative of bureaucratic orchestration

Notwithstanding such consolidation, there are several reasons why global challenges can benefit from greater pluralism if it can be done right.

First, OGDs can leverage the full range of a government's human resource capacities behind critical global public goods. For example, in 2018, education departments were the top OGD benefitting from ODA finance, followed by environment and health ministries (Table 1).

Table 1: Frequency of commonly used OGD by type of ministry in 2018

| Type of ministry | Frequency of use in 2018 |

|---|---|

| Ministries of education or higher education | 23 |

| Ministries of environment or climate change | 22 |

| Ministries of health | 21 |

| Ministries of interior or home affairs | 18 |

| Ministries of agriculture | 16 |

| Ministries of defence | 16 |

| Ministries of labour | 15 |

| Ministries of industry, economy or competitiveness | 14 |

| Ministries of infrastructure or transport | 14 |

| Ministries of justice | 10 |

| Research institutes | 8 |

| Ministries of culture | 5 |

| Ministries of immigration or agencies responsible for asylum-seekers | 5 |

| Police services | 5 |

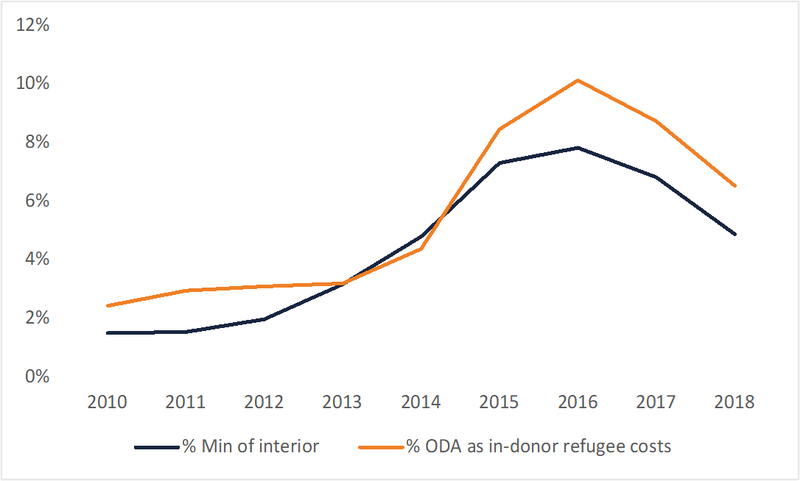

At the same time, global events can also propel OGD engagement to address live challenges. For example, when the number of global asylum seekers jumped from 1.8 million in 2014 to 3.2 million in 2015, there was a rising share of ODA allocated through interior ministries. This was a practical response to a live global challenge, incentivised by the ability to count first-year refugee resettlement costs as ODA (see Figure 4).

Figure 4: Tracking percentages of ODA through interior or immigration ministries alongside in-donor refugee costs

Furthermore, a more expansive and integrated understanding of global development responds to demands from partners for world-class expertise and knowledge. OGDs can leverage skills and experience that both improve and deepen interventions to degrees that are not possible if they are uniquely reliant on generalists without sectoral expertise. Odds are higher of finding a geoscientist or public health specialist in government departments with science-focused mandates, even as the tendency to outsource specialised technical skills in the public sector grows.

Finally, sourcing knowledge and capacities from wherever it is held across government nudges line ministries towards global policy spaces, potentially bringing greater coordination between domestic and international agendas. Consider for example the ways the Covid-19 pandemic has placed a spotlight of the role of domestic health agencies in global public health in arenas like vaccine procurement, driving forward momentum in (but admittedly also weakening) equitable vaccine distribution in the poorest countries.

Notwithstanding the benefits of engaging OGDs, care needs to be taken that bureaucratic pluralism does not descend into bureaucratic fragmentation. Departments need the capacity to implement programmes and generate real value, and both need active monitoring. For example, should we be concerned that Germany allocates climate-related ODA through eight line ministries beyond BMZ, its lead development ministry? Is the resulting fragmentation real, imagined or an inconsequential by-product of its autonomous federal structure? If widening the responsibility for ODA to other departments can potentially reduce efficiency and impact, an inventory of the realised benefits and costs of drawing in a wider range of actors can help assess net results.

What's needed now

Global challenges clearly demand donors put in a whole-of-government effort. To reap the rewards of bureaucratic pluralism and avoid the costs of fragmentation, however, a donor should do three things.

First, providers need a clear strategy for their OGD engagement. This would include assessing which department is best able to contribute to a given global challenge, outlining basic standards against which bureaucratic performance on development objectives will be judged, and reporting on realised costs and benefits. For example, Denmark maintains a clear division of labour between its foreign and climate ministries on climate-related development finance, with the former focusing on low-income countries and the latter on limiting future climate emissions in ODA-eligible emerging markets. The impact of Denmark’s climate spending for both ministries is tracked using clear performance indicators laid out as part of the ‘Guiding Principles’ for its climate envelope.

Clarity on objectives and expectations on OGDs satisfies demands for public accountability and avoids ODA allocations being diverted to top up ministry budgets for non-development related activities. A strategy could also introduce a ceiling on ODA funding disbursed through OGDs to avoid excessive fragmentation, recognising that its level will need to adapt to the nature of line ministry engagement with ODA resources. For example, if a health ministry is merely acting as a conduit for investments into strongly performing multilateral institutions, this may be less problematic for cross-governmental coherence than if funding were being used for bilateral programmatic investments where the risks of incoherence are heightened. An OGD strategy might also outline how donors should be engaging with blended finance institutions that often sit one step removed from core governmental institutions, including how they should be monitored and evaluated.

Second, to maximise governmental efforts in tackling complex global challenges, strong departmental capacities must intersect with robust cross-governmental systems. Many OGDs have limited prior history working in aid policy and administration, and weak departmental capacities can jeopardise programme design and implementation. In the UK, for instance, the 2015 Aid Strategy increased pressure on DFID to support inexperienced OGDs in their aid management, including assessing ODA eligibility, complying with public accounting standards and managing development programmes. One might go so far as to say that the demise of DFID in 2020 may be attributable to perceptions of inefficiency and opacity deriving from weaknesses in departments other than DFID. Individual departmental competencies must sit within a web of intergovernmental systems that enables trust, information-sharing, joint human resource management and collective decision-making. Without this bedrock, engaging in complex international operational missions – as the recent evacuation efforts in Afghanistan by NATO members highlight – are destined to fall short.

Finally, tackling global challenges needs donors to enable arm's length oversight and leadership by central agencies. Central offices of governments, like treasuries and cabinet offices, are ideal in such a role because of their independence from core bureaucratic operations and their overarching view of government policy and practice that can allow them to monitor delivery and whole-of-government impact. They also have official mandates to arbitrate across units of asymmetric size and power and can push for greater cross-governmental coordination; better coherence in planning and budget allocations; and elevated departmental performance and ambition. Investing overall leadership in any single line department can ultimately be a source of bureaucratic conflict of interest. For example, in the UK the FCDO was put in charge of a cross-governmental review of the 2021/2022 ODA budget allocation, even as it stood to disproportionately benefit from this agenda-setting position. Putting central agencies in this role allows for something closer to neutral arbitration in intergovernmental debates over ODA funding and policy, nourishing bureaucratic pluralism while avoiding the pitfalls of fragmentation.

Global challenges point to a changing role for development bureaucracies. Independent bureaucratic action – whether by a development or foreign ministry – is no longer suited to tackling cross-cutting existential threats. A more horizontal understanding of international cooperation is gradually pushing collaboration among bureaucratic counterparts and displacing the more hierarchical approaches of the past.

At the same time, pluralism cannot justify policy incoherence or administrative duplication. While many countries have sought bureaucratic consolidation through the vehicles of formal mergers, this level of integration is not a necessary precondition for orchestrating pluralism. Indeed, mergers can become backdrops against which fragmentation and hierarchy can escalate. This is especially likely in the absence of a strong vision for development policy and the role that OGDs should play; where there are weak bureaucratic and intergovernmental systems; and where no central agency is impartially steering policy forward. Achieving a symphony of global goals ultimately requires donor governance systems to unite the melodies from individual players under the baton of a first-rate conductor.