Since the onset of the Russia-Ukraine war, the Central Asia region has begun a gradual pivot away from Moscow’s orbit, despite its strong economic and commercial links with Russia. Although significant ties remain with Moscow, the war has created a range of socio-political and economic consequences across the region which has led to other countries competing for influence to counter the Kremlin offer.

Turkiye, for example, is a country which has steadily expanded its ambition to become an alternative player in the region. In the last decade Ankara has renewed its approach to bring together the Turkic world by advancing a shared Turkic identity and culture. One mechanism by which Turkiye aims to achieve these goals is through the Organisation of Turkic States (OTS), established in 2009 as an intergovernmental organisation with Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Turkiye as its founding members. Uzbekistan was admitted in 2019, and Hungary, Turkmenistan, and the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus currently hold observer member status. Earlier this month, the OTS, which has gained momentum since the war, convened their annual summit in Samarkand, Uzbekistan, focused on furthering economic integration and developing connectivity routes.

The Russia-Ukraine war has also exposed risks associated with global supply chains and transport routes. Within this context, the Trans-Caspian International Transport Route (also known as the Middle Corridor) has subsequently gained a new impetus. The Middle Corridor, a joint venture between Azerbaijan, Georgia, Kazakhstan and Turkiye, links China and Europe via rail freight transport networks and shipping systems across Central Asia, Turkiye, the Caucasus, and the Caspian Sea and further on to European countries.

Considering the geopolitical volatility resulting from the Russia-Ukraine war, the Middle Corridor is considered as a reliable alternative route which bypasses Russia. Turkiye not only plays a crucial role in the route’s advancement, but it has also been vocal in promoting it as a stable and dependable route that will help prioritise connectivity routes independent not only of Russia but also Iran. By advocating the Middle Corridor as the strongest transport alternative, Turkiye aims to use it to consolidate its regional positioning by becoming a key transit country adding to its strategic importance.

This renewed drive towards the Middle Corridor has also been welcomed among Central Asian states, especially within the context of diversifying relations from Russia. Uzbekistan views the route as an opportunity to increase its position in relation to logistics and energy. Last week, Kazakhstan announced that it will begin exporting oil through the Middle Corridor from 2023. The route has also garnered interest from the EU, which continues to search for alternative sustainable trade routes bypassing Russia.

Turkiye has been key to putting the Middle Corridor back on the agenda, a route which China had previously prioritised as part of its Belt and Road Initiative to foster regional market connectivity. However due to the strong emphasis on intra-regional cooperation, Turkiye has seen more progress on pushing for cooperation on the Middle Corridor and enabling Central Asian countries to commit to the route. Yet Turkiye also recognises the added advantage of cooperating with China on the Middle Corridor, which was reflected in August during a meeting between the two countries’ foreign ministers with Turkiye stating that “Ankara attaches great importance to the synergy between its Middle Corridor initiative and the Chinese BRI”. By engaging with China, one of Central Asia’s biggest investors, Turkiye avoids an unnecessary confrontation with Beijing on the future of this corridor.

Yet challenges remain before the Middle Corridor is considered the most viable alternative route. The lack of modernised infrastructure is an issue, with considerable financing required to upgrade it. The route also faces limitations regarding capacity, and the time involved for the cargo transportation. A common customs union will also need to be established as well as digital integration for the involved countries. Measures to address digital transport communications were announced at the latest OTS Summit where Kazakh President Tokayev proposed to establish a Centre of Digitalisation of the OTS to contribute towards the region’s digital development. This will help facilitate efficient exchange of transport documentation and accelerate digital solutions for trade, transport, and information security.

In line with Turkiye’s aim to forward itself as a key connector across Europe and Asia, its ambition does not remain limited to the Middle Corridor. The recent decision at Samarkand to establish the Turkic Investment Fund, a scheme to mobilise the economic potential of the members while also strengthening trade and economic cooperation, will support the OTS economies to further regional financial integration, with Turkiye at its helm. Economic integration went even further with Kazakhstan’s proposal to set up a Turkic Green Finance Council, which could be based at the Astana International Financial Centre.

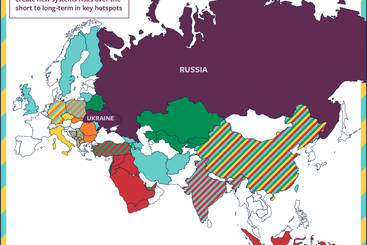

With so much of Russia’s focus invested in Ukraine, Turkiye has benefitted from the new opportunities created for further engagement across Central Asia and will utilise organisations like the OTS to consolidate its position in the region. Such advancements should not be viewed as short-term gains but rather as part of a wider reshaping of the regional order. For how long Turkiye will be able to pursue its Turkic agenda before Beijing also seeks greater influence remains to be seen but for the short-to-medium term, Turkiye has re-gained a strong footing in the region.