What is the case against?

There are three common myths about increasing aid for infrastructure in the poorest countries:

1. ‘Aid will have less impact because it is likely to be wasted.’

Waste in infrastructure spending is particularly visible. Aid for other purposes may also be inefficient, but will not result in a ‘bridge to nowhere ’.

Poor countries are also liable to have weak institutions, which means that wasteful spending is more likely.

Yet a recent IMF paper has shown that there is no detectable relationship between the efficiency of public investment and the impact on growth of these investments.

Why might this be? Compare the construction of a 22MW wind farm in Liberia and the UK.

The UK wind-farm would most likely cost far less; but the impact of the wind farm in Liberia would be much greater (doubling the total installed generation capacity) than in the UK (where it would add less than one thousandth of a percentage point).

1. ‘The private sector can fill the financing gap.’

To date, private financing for infrastructure has tended to be concentrated in richer countries. In 2014, 73% of the private infrastructure financing commitments were in just five countries – Brazil, Colombia, India, Peru and Turkey.

This is not surprising. Although the potential benefits of ‘crowding in’ other investment are likely to be much greater in the lower income countries where infrastructure is most needed, these benefits may not be monetised. Political risks, institutional weaknesses and weaker demand also deter potential investors.

There are examples of private investments in infrastructure in the poorest countries; but typically the subsidies required to attract investors and ensure services are affordable are likely to be greater than in richer countries.

3. ‘Low income countries are unable to absorb more aid for infrastructure.’

There is some evidence that the inefficiency of investment rises when governments try to rapidly scale up infrastructure provision.

However, many absorptive constraints arise from donors themselves. The average time taken by the World Bank to prepare and disburse a loan is still 25 months.

Outsourcing can help to alleviate absorptive constraints. Although Chinese infrastructure projects are criticised for not using local labour and systems, they demonstrate that there are ways around capacity constraints.

Innovative contracting models are also changing the incentives contractors face, including construction and maintenance in a single contract.

What should donors do?

The overall envelope for development assistance is unlikely to rise in the coming year; giving more aid to infrastructure in low income countries will require reprioritisation. This means moving money from richer countries to poorer countries or shifting money between sectors.

Donors need to stop relying on these myths about infrastructure aid, and instead look for new ways to support infrastructure in the countries where this will have the greatest impact.

The news so far this year has made for sobering reading for low income countries. Their economies have been buffeted by falling commodity prices and continued concerns over the health of the Chinese economy. In a speech earlier this month, Christine Lagarde stated that ‘on current forecasts, the emerging world will converge to advanced economy income levels at less than two-thirds the pace predicted a decade ago’.

At the same time, aid flows are falling to the countries that need it most. Although aid flows from OECD countries increased by 1.2% in 2014, the share going to low income countries fell by 5%, to less than a third of the total.

What is the case for increasing aid for infrastructure in the poorest countries?

At the same time aid is falling to the lowest income countries, consensus is rising on the importance of infrastructure for promoting economic growth.

This has been dismissed as ‘capital fundamentalism’. But there is good empirical evidence that infrastructure investment can ‘crowd in’ private capital in low income countries. Dani Rodrik recently highlighted Ethiopia, India and Bolivia as countries where public investment is driving growth.

Aid for infrastructure can support growth in the poorest countries where it is most needed, and can support counter-cyclical investments to boost demand in countries feeling the ill-winds of falling commodity prices.

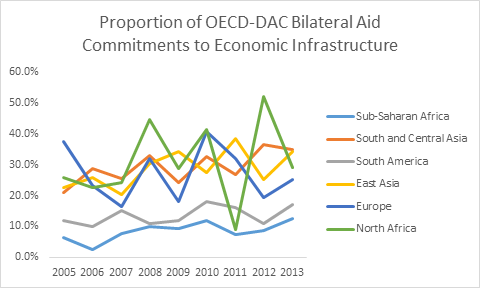

Despite this, the proportion of OECD aid going to infrastructure in the world’s poorest region, sub-Saharan Africa, although rising, is significantly lower than in other parts of the world.