The Russian war in Ukraine has had a devastating impact on the country’s people, infrastructure and economy. According to the UN, almost 3,000 civilians have been killed or injured, 6.5 million are internally displaced and 4 million have been forced to flee to neighbouring countries. The Ukrainian government puts the economic costs of the war at some $570 billion and counting. While the Russian offensive appears to be stalled for now and tentative talks are under way in Turkey, there seems little prospect of a swift end to the fighting.

The conflict is also having reverberating effects globally, in terms of rising commodity prices, energy shocks and the emerging geopolitical consequences of a conflict in the heart of Europe instigated by a nuclear-armed state and a P5 member of the UN Security Council.

Economic shocks

While the war is for now at least confined to Ukraine, its economic spillover effects will be felt worldwide. Russia and Ukraine together account for just 2% of global trade and gross domestic product (GDP), while the stock of foreign direct investment in Russia and by Russia amounts to about 1% of the global total. Both are, however, major suppliers of commodities: wheat, maize, sunflower, fertiliser, fuel and metals, whose prices have sharply increased since the start of the conflict. Based on a likely conservative assumption of a 10% increase in global prices of wheat, food, fuel and metal products over the year, we estimate that the negative impact of the war through trade channels of these products on low- and middle-income countries (L&MICs) to be worth at least $18 billion this year (Raga and Pettinotti, forthcoming). East Asia and Pacific countries – mostly oil importers – might experience the most negative impacts this year, worth $29 billion, followed by South Asia ($15 billion). There are likely gains at the aggregate level for countries in the Middle East and North Africa and sub-Saharan Africa, driven by increased global prices for their oil exports.

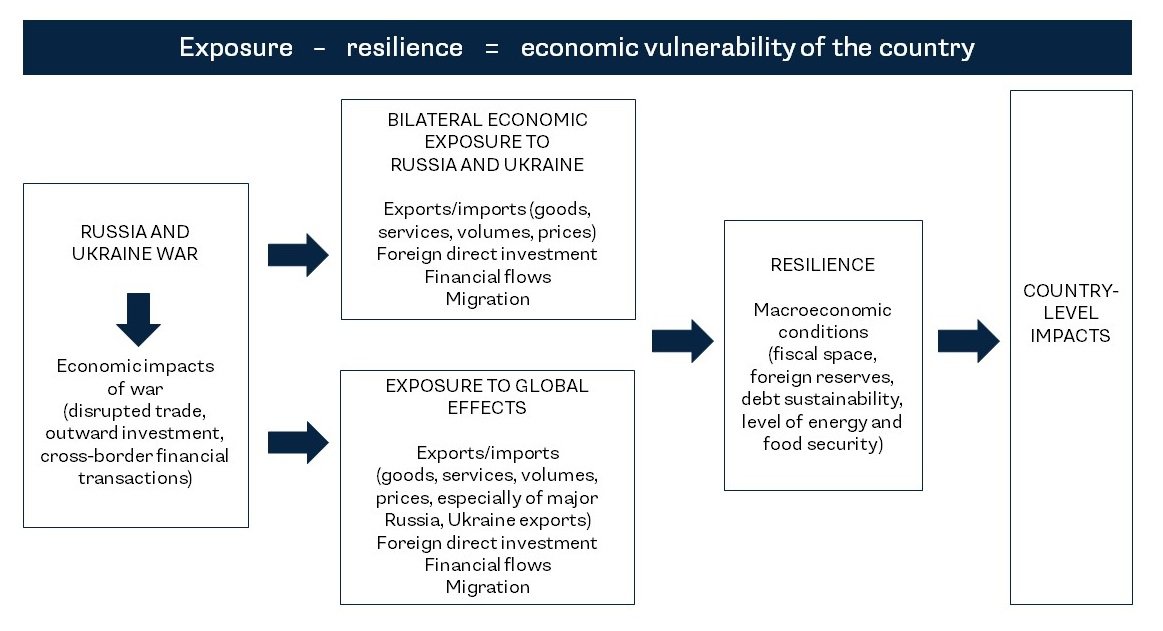

We examined the economic vulnerability of 118 L&MICs to the impact of the war by using 27 indicators measuring their direct economic exposure to Russia and Ukraine (e.g. bilateral trade, investment, migration); their indirect economic exposure to global effects of the war (e.g. commodity exports, trade and investment openness); and their resilience (e.g. fiscal space, foreign reserves, dependence on food imports, use of renewable energy) to mitigate the negative impacts of external shocks that may emerge from the war. The top five most vulnerable countries on these measures are Belarus, Lebanon, Kyrgyzstan, Armenia and Uzbekistan.

While the most vulnerable countries in terms of direct economic exposure to Russia and Ukraine are mostly those with geographic and historical proximity to Russia (Belarus, Armenia, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan and Tajikistan), countries from other regions might be negatively affected through global effects due to their reliance on commodity imports, remittances and tourism (e.g. Jordan, the Maldives, St Vincent and Grenadines, Jamaica) or through weak resilience due to pre-existing high levels of debt, inflationary pressures and poor governance (e.g. Syria, Yemen, Sudan and Lebanon, and Least Developed Countries (LDCs) such as Gambia, Comoros and Sierra Leone).

Figure 1

Food security

Ukraine and Russia are among the world’s largest exporters of wheat and maize. Ukraine is also a major exporter of sunflower oil. Harvests in Ukraine will probably be much lower than expected in 2022, while occupation and the blockade of Ukraine’s Black Sea ports means that, even if crops are harvested, they may not be exported. The war also means the Black Sea has become dangerous for shipping: insurance is reportedly hard to buy, and most captains will not enter. This raises questions about the ability of Russia to export its harvests as well.

Russia and Ukraine are also major producers of urea fertiliser, and Belarus of potash. Both would, like crops, be hard to export. We are seeing (mid-March 2022) remarkable increases on world markets of prices for grains and fertiliser. Prices for maize, soybeans and wheat on world markets have risen by 75% to 89% over where they were six months ago, in September 2021. Urea fertiliser prices are up by a similar margin. Prices for potash and oil have risen by half since September.

Although many people in low- and lower-middle incomes countries do not consume much wheat, some do, such as Egypt, Lebanon, Sudan and Yemen, and import most of the wheat consumed, much of it from Russia and Ukraine. African LDCs relied on Ukraine and Russia for 39% of their wheat imports in 2018–2020. Either prices of bread will rise, and with that so too will unrest, or the cost of public subsidies – as seen in Egypt and Sudan – will soar.

Energy shocks

Russia is a major supplier of crude oil (15% of global crude oil exports as of 2020) and oil preparations (10%). The shortage of supply globally due to the war will push global prices up (e.g. Brent crude prices spiked by 56% between 3 January and 7 March, and remain significantly higher than before the invasion). Higher prices will have a positive impact on net oil exporters in many African countries. The impact on Asia is ambivalent; disruptions in commodity prices and commodity supply chains will impact Asian growth negatively, but there are several potential counter-measures. ASEAN will try to trade with Russia through China, which has itself been stockpiling commodities and agricultural produce since last September, and is therefore insulated against disruptions and price accelerations. India has signed a two-year deal with Russia to buy discounted oil, and Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov is in New Delhi very soon to discuss reviving the Soviet-era rupee rouble trade settlement agreement.

Russia is also the world’s second largest gas producer and supplies around a third of the gas burned in Europe. While some European countries are more reliant on Russian gas than others (particularly Bulgaria, Germany, Finland, Italy, Latvia and Poland), Russia’s dominant role in Europe’s energy ecosystem is a significant factor in the way Europe is responding to its actions in Ukraine.

In the short term, there will be pressure in some countries, notably Germany, to turn coal plants back on to meet electricity demand, with as yet unknown effects on emissions targets. Over the longer term, as countries seek to reduce their dependence on Russian oil and gas, we may see increased investment in energy efficiency and renewable generation in Europe. This has the potential to accelerate decarbonisation. However, we may also see new oil and gas licences issued to expand supply, both to enhance energy security and because high prices make previously unviable wells commercially feasible. This is likely in the United States, especially given recent defeats of large parts of President Biden’s clean infrastructure legislation.

Geopolitical shocks

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is a direct challenge to the post-war order in Europe, expressed through multilateral institutions such as the EU and NATO and underpinned by US power. Whether these structures buckle or whether the Russian challenge reinvigorates them remains to be seen. It is also unclear how China will ultimately calibrate its relationship with the West and with its Russian neighbour. China has actively prepared for a period of geopolitical turmoil, stockpiling oil and commodities in a reserve buffer, and has maintained cordial relations with Russia. Beijing is well-placed to enable L&MICs to minimise the negative impacts of the conflict. Many Asian and African economies are scarred by debt and dependent on Chinese inward investment and commodity demand. How China handles the crisis response is therefore key to whether geographies outside Europe are likely to face more fraught geo-economic times going forward.

Several things are already clear. European governments’ refugee policies are again under the spotlight, raising difficult practical and moral questions regarding countries’ responsibilities under refugee law. Acts of solidarity towards Ukrainians fleeing conflict are a welcome reminder of our shared humanity, but they also cast an unflattering light on the less than generous positions some governments have adopted in relation to refugees seeking safety from more distant conflicts.

There is also a very real risk that the upheaval and instability generated by the conflict will provide an opportunity for organised crime and human trafficking groups to increase their activities in the country and use it as an alternative smuggling route into Europe. Organised crime and corruption have been a major challenge in Ukraine for years, and were core issues leading to the Orange Revolution in 2004–2005. Reported transfers of Russian peacekeepers from the South Caucasus to Ukraine also increase the risk of an escalation of the so-called ‘frozen’ conflicts in the region. Since the beginning of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, tensions between Armenia and Azerbaijan over the disputed Nagorno-Karabakh region have escalated, culminating in numerous ceasefire violations in recent days.

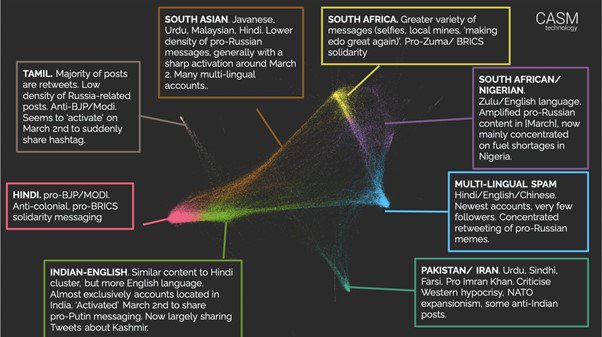

Less clear are the wider global implications of the conflict, and the breakdown in the West’s relations with Russia that it has precipitated. While geographically this war is in Europe, how the geopolitics of the conflict play out in the coming months is likely to reshape, not just the landscape of Europe, but also the long-standing patterns of relations between the Global North and the Global South. It is no accident that, while much has been said about Kyiv ‘winning’ the information war with Moscow, Russia hasn’t really been fighting that war in the cyberspace inhabited by the West: its attention has focused on the BRICS, Africa and Asia. Notable too is the lack of condemnation of Russia’s actions from African governments mindful of the history of Soviet support during the Cold War. This is a contest for global influence being fought on multiple fronts.

Figure 2

Post-1945 institutions such as the UN Security Council are likely to survive, but growing polarisation among P5 countries will reduce their ability to function as effectively as they did after the end of the Cold War, and the conflict is likely to damage normative areas of the system.

The decision to freeze Russia’s access to central bank reserves and Special Drawing Rights has once again highlighted the willingness of the US to use the dollar-dominated financial system to secure strategic advantage. Beijing may decide to accelerate efforts to develop alternative systems to challenge the hegemony of the US dollar in the global economy, especially leveraging the crypto space. More generally, the G20 finance track is likely to become more fractured, with potential implications for other live agendas such as advancing a common approach to debt relief or scaling up sustainable finance.

As the US and Europe shift their attention and financial resources to the conflict in Ukraine, other development and humanitarian challenges are being deprioritised. While signing off on $13.6 billion of military and humanitarian support to Ukraine, the US Congress has rejected proposals to increase financial aid to tackle Covid-19 and to reallocate its SDRs. Meanwhile, European governments are increasing defence budgets, while also struggling to deal with the mass influx of Ukrainians into their countries. Following through on global vaccination programmes, or addressing the growing crisis in Afghanistan, seem to have fallen off the political radar.

For the multilateral development banks (MDBs), the financial impact of the crisis does not pose any serious threat to the long-term financial stability or credit rating of either the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) or the World Bank Group. Nonetheless, loan write-offs, increased loan loss provisioning and market-to-market equity investment losses will tighten the lending headroom of the EBRD and the World Bank at a time of very pressing needs.

The New Development Bank backed by the BRICS nations may be impacted by exposure to Russia as both a shareholder and borrower, but has fully underwritten its lending portfolio and has also stopped fresh lending to Russia. The China-led Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank will be much less affected, at least in the near term, as it has a much more diversified loan portfolio with limited Russia exposure.

China is already attempting to fill the vacuum left by Western-backed institutions, offering development assistance to LMICs affected by the economic fallout of the war. This compounds the perceived lack of solidarity from the West during the pandemic by public opinion in most LMICs.

Conclusion

The human costs of the war are clear and unsettling. Aside from its direct impacts, the war has come as an unwelcome additional shock to global and national economies still reeling from the impacts of the pandemic. Unlike March 2020, where countries were facing a common enemy with a common set of policy instruments to tackle it, the Ukraine crisis is having global reverberations that are affecting different countries in very different ways. This will likely place stresses on systems of economic and political cooperation that go beyond the conflict itself, and will be felt within the Western alliance, in the West’s relations with Russia and China, and in the relationship between these centres of power and the Global South. Much is at stake.

The author would like to acknowledge the contributions from Sarah Colenbrander, Marta Foresti, Stephanie Diepeveen, Matthew Foley, Mark Miller, Rebecca Nadin, Kathryn Nwajiaku-Dahou, Laetitia Pettinotti, Sherillyn Raga, Rathin Roy, Theo Tindall and Steve Wiggins to this analysis.