The current global spread of Covid-19 offers the latest clarion call for building universal systems as a cornerstone of health policy. The outbreak highlights that effective containment policies must provide ready access to quality healthcare for all, but also include dedicated attention to those most at risk.

Our new paper – launched today – explores the constraints a diverse range of groups experience to accessing quality healthcare. Some of these groups are less commonly studied (LGBT individuals, sex workers, migrants and forcibly displaced people) while others have have been subject to more extensive research (persons with disabilities, those living in rural areas). It finds that dedicated, context-specific interventions are required for universal healthcare to truly reach those who need it most.

Health coverage is a political issue first

In earlier research on the development of universal health systems in around 50 countries, colleagues and I highlighted that most major moves toward universal health coverage (UHC) occurred following episodes of fragility which up-ended ‘business as usual’. We also found that country wealth was not a major determinant of progress among low- and middle-income countries and that once UHC was achieved, it tended to persist.

Together, these findings converged upon an important message. If post-conflict countries and those undergoing reconstruction can create stable health systems, and if those implementing UHC are only slightly wealthier than those who cite finance as a barrier, the main obstacle to UHC roll-out appears to be political.

Creating the will to push through such reforms is difficult although far from impossible, as the experiences of countries as diverse as Costa Rica, Rwanda and Sri Lanka illustrate. But even universal systems are unlikely to meet the needs of at-risk groups without additional targeted support. For instance in China, despite ‘nearly universal health coverage’, some 45% of elderly households experienced catastrophic health expenditures (payments exceeding 10% of their income) compared with around one quarter of the entire population.

Overcoming barriers to access for vulnerable groups is crucial

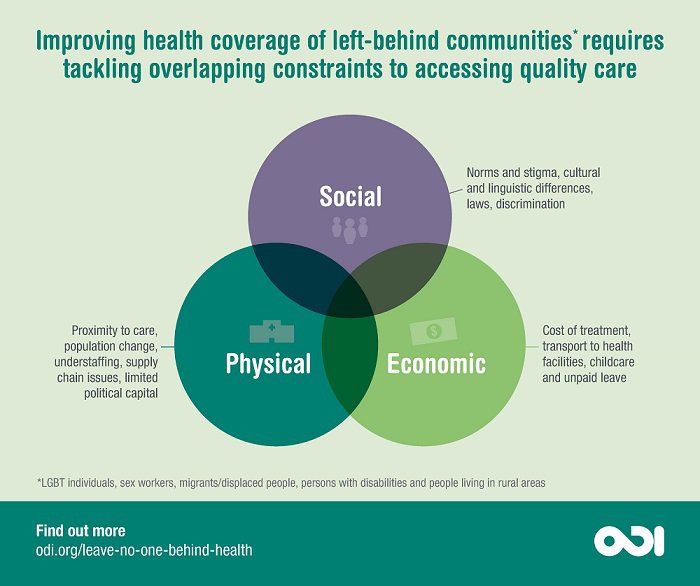

Most barriers to healthcare access are social, economic or physical in nature, but the way they are experienced will vary for specific groups. In Nigeria, passage of the Same Sex Marriage Prohibition Act in 2014 led to a marked decline in the number of men with male sexual partners taking HIV tests due to an increase in fear of seeking healthcare, blackmail and verbal harassment. In Brazil, a survey showed that 60% of 241 primary healthcare facilities (basic health units) across 41 municipalities were not physically accessible to elderly people and those living with disabilities. Meanwhile migrants (PDF) across the world – particularly those lacking documentation – often cannot afford care and avoid it for fear it will be used as a tool of immigration control.

The diverse nature of these constraints and the way they are experienced singly and jointly means that targeted interventions should proceed, accompany and follow reforms aiming at UHC. Again, there is no one-size-fits all approach. In Ghana, for example, drones deliver live-saving supplies to remote rural areas within 30-40 minutes; as of May 2020 this year they reached over 2000 hospitals covering 12 million people. In Thailand, a review of and change to outdated and stigmatizing legislation that was reducing the uptake of health services by gay men and transgender persons cost the government about $32,000 USD. This is the equivalent of treating four people for HIV for a period of twelve years in South Africa, the country with the most similar income level.

It’s clear that countries must make many important judgments in deciding how to support the health of their populations. A classic trade-off is how much to spend on preventative and curative healthcare versus broader investments such as providing clean drinking water and adequate sanitation. But beyond this, they must balance the building of universal health systems with support directed towards the specific needs of vulnerable individuals and communities. It will not be enough to rely on UHC alone – even within universal systems, targeted interventions are critical.