Every year, 1.25 million people are killed in traffic collisions worldwide – it’s the leading cause of death for young people. Despite this, road safety continues to be overlooked by governments, non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and the public at large.

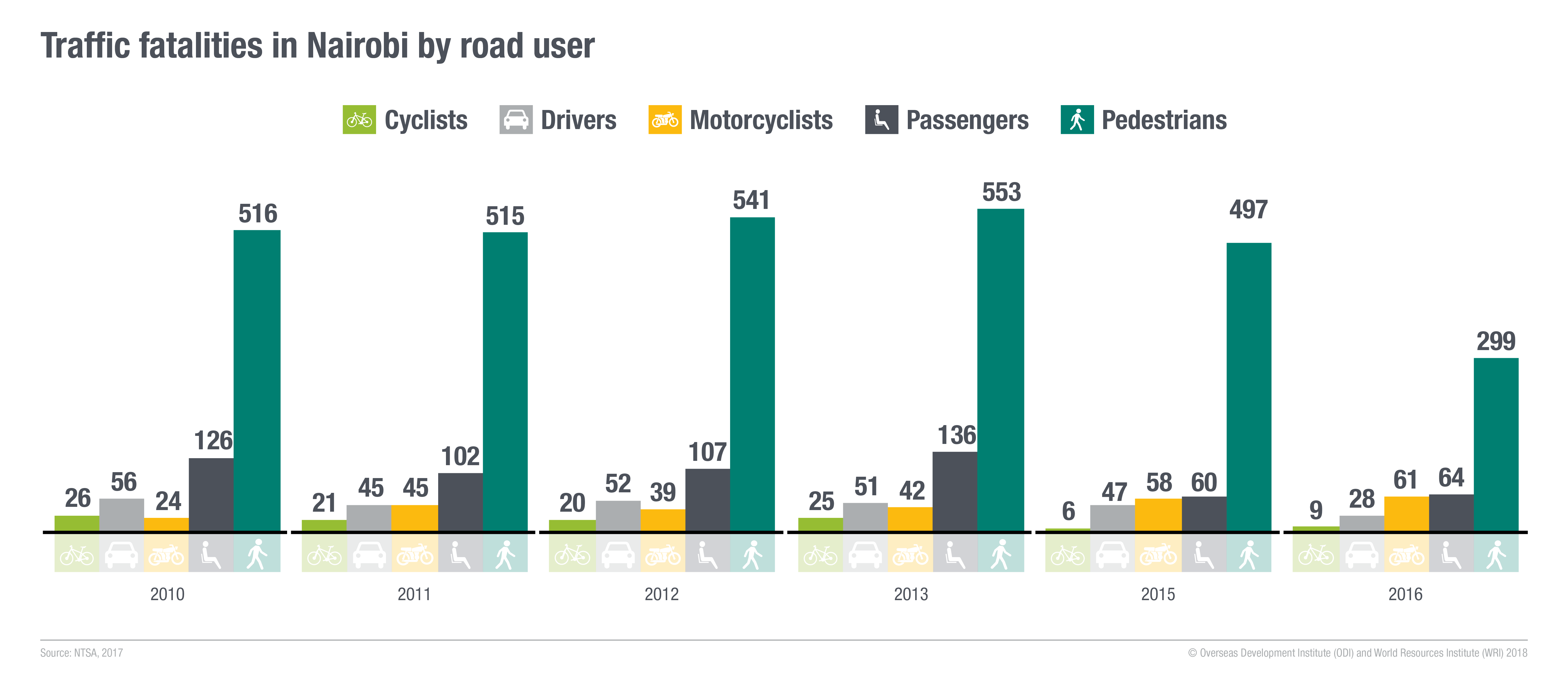

Together with WRI’s Ross Center for Sustainable Cities and the FIA Foundation, we set out to understand why road safety is not getting the attention it needs. As part of our research, I spent time in Nairobi with a Kenyan journalist, speaking to government officials, transport unions, NGO advocates and bus drivers. In 2016, 461 people were killed on Nairobi’s roads. What explains the persistently high rate of traffic fatalities in the city?

Sacrificing safety for speed

In Nairobi, the call for faster roads is louder than the call for safer ones. The city is growing and spreading; more and more people are making longer and longer commutes from home to work or school every day. Most of these commuters aspire to own a car. It allows them to avoid the crowded and chaotic minibuses (matatus) and is a status symbol. Yet the congestion is notorious and affects everyone, every day. So politicians pour money into road construction, in a clear sign to voters of government action. Road safety just isn’t prioritised.

In 2015 and 2016, more than half of all fatalities happened on Nairobi’s new high-speed roads. Yet nobody questions whether a multi-lane highway is the best option for improving mobility in the city. Politicians claim, often convincingly, that road safety measures will slow travel times, anger car-users and damage the economy. And the matatu owners worry such measures will reduce their profits.

As we found in our research, it is much easier to see road safety as a personal responsibility than as the result of inadequate public transportation or road safety measures. Road users are almost invariably blamed for collisions: either ‘pedestrians don’t use the foot bridges’, or ‘drivers don’t respect the rules’, or ‘the traffic police take bribes’.

The need for collective action

However, as our research shows, responsibility for road safety does not lie with the individual alone. Consider the following.

Matatu drivers are frequently blamed for reckless driving. But they need to make as many journeys with as many passengers as possible so that they can scrape out a living. It is little wonder that they drive long shifts, don’t stop for repairs and take risks to get ahead of the traffic. Road design, urban planning, public transport provision and protection for pedestrians (usually the poorest people in the city) all contribute to how people move around Nairobi – often not very safely.

This is an urgent challenge, not only of infrastructure but also of governance and collective action. But how do you turn road safety into a priority, if people don’t see it as one?

The power of ideas

A key objective of our project was to bring a new perspective to road safety. We want to shift the debate beyond calls for more regulation and training towards a focus on the need for collective action to push for improvements that serve everyone – including pedestrians, cyclists and motorcyclists. As we developed the project, we hoped that campaign groups would be interested in thinking about how to make road safety a political priority and how they could collectively lobby for safer road design.

With this mindset, I was back in Nairobi two weeks ago to discuss the findings from our research. Attendance at the event we organised was high, and the enthusiasm palpable. Questions from the audience poured forth: Why isn’t the government building cycle lanes? Why don’t we roll out ride-sharing apps? When will the non-motorised vehicle policy actually be implemented?

Yet, when we turned to practical steps, what was it that people care about most? … That’s right, making drivers drive better. There was little mention of the broader, systemic road safety issues we emphasised in our research.

What I learnt from this brief foray into advocacy reinforced the findings of our research – that shared ideas and public attitudes are critical in shaping perceptions and policy responses to road safety. Political economy analysis often focuses on conflicts of interest, but we need to pay more attention to the power of ideas too. The perception of road safety as a personal responsibility is a major barrier to progress. To support campaigners in Nairobi, and elsewhere, who are striving to make roads safer, we need to know how to shift attitudes so that policy change is possible and regulations are respected. This is something the city of Bogotá has done well and which we can learn from. Until there’s a shared understanding of safety as a public good and collective challenge in Nairobi, investments in infrastructure, regulation and training will continue to be undermined.