As the Russia–Ukraine war drags on, its geopolitical consequences are becoming ever clearer. The cascading risks of the conflict are creating shocks to long-standing global peace and security arrangements whose durability we have long taken for granted.

These risks are not necessarily new, and in many cases exacerbate existing trends and vulnerabilities across systems. While some of these vulnerabilities are more tangible and immediate, such as to food and energy security, other emerging risks remain poorly understood.

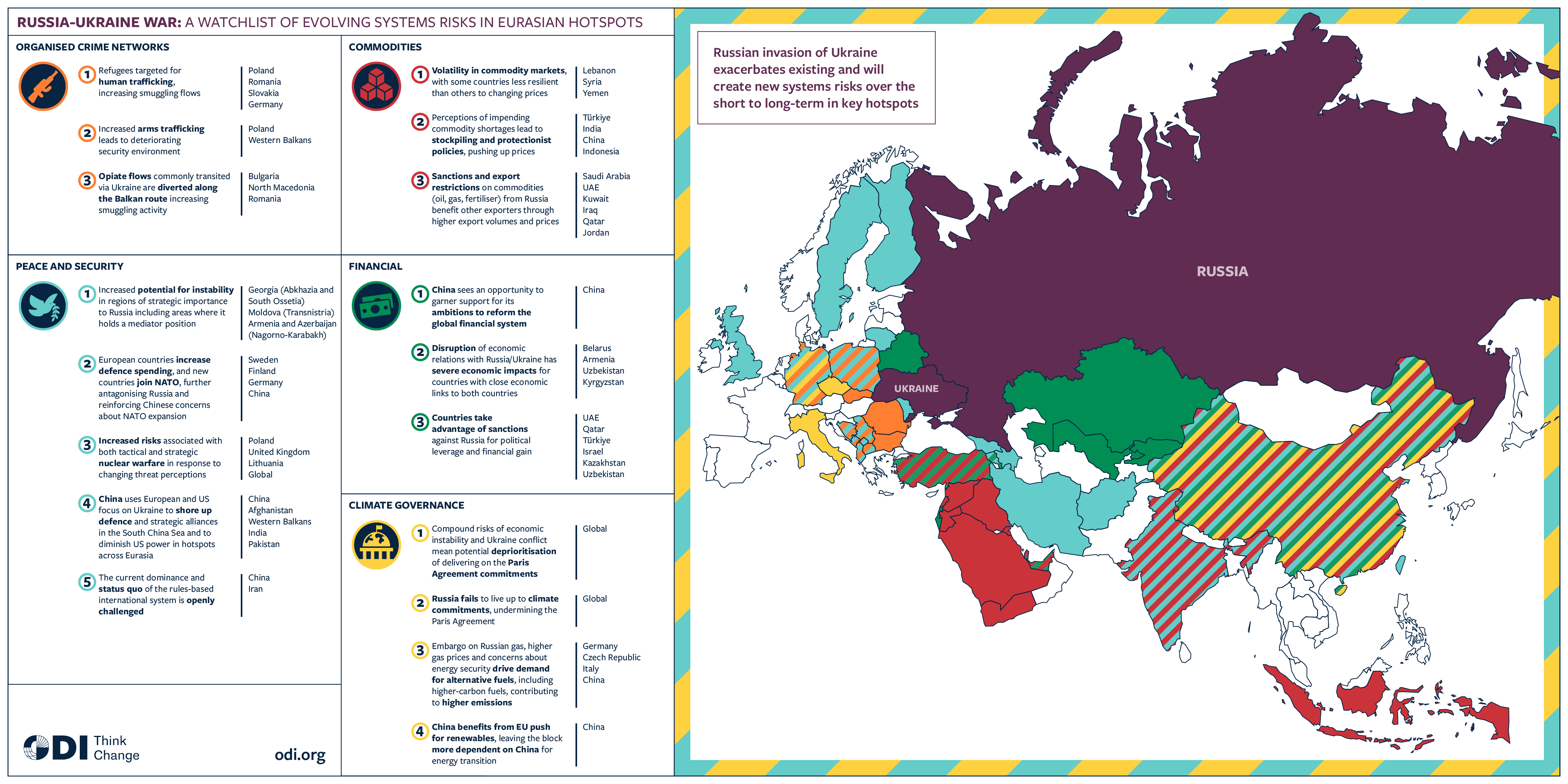

Our analysis of evolving systems risks looks beyond energy and food systems. By analysing risks across global systems – peace and security, financial, organised crime, climate governance and commodities, in key Eurasian hotspots – we highlight broader risks generated by the war, which decision-makers across sectors need to watch carefully.

Climate governance

When it comes to climate governance, the real risk is that the compounding shocks of economic and energy instability lead governments to deprioritise delivering on the Paris Agreement as high living costs and security needs top the political agenda. Both climate policy and commitments to the Paris Agreement have always been political at the national level, but the Ukraine war has demonstrated just how vulnerable they are to geopolitical shocks. Trust is key to any international agreement and the Western response to the energy crisis, in the eyes of some states, has created an erosion of trust.

Several African countries have also called out what they see as the West’s ‘energy hypocrisy’. In recent years, African nations have sought financing for fossil fuel projects to meet their energy needs but have struggled to secure the finance as Western governments have urged lenders to push back on such projects. But with high-level visits by the German Chancellor Olaf Scholz to Senegal and by the Italian President Sergio Mattarella to Mozambique to discuss gas field development and energy collaboration, fossil fuel projects seem to be back in favour with European nations.

What we are likely to see as a result are ‘disrupted’ transitions, meaning that, over the coming decade, countries might waver on reducing emissions as other priorities take precedence. When it comes to transition from fossil-fuel economies towards lower-carbon ones, adopting net zero strategies is the very first step in a long process and by no means an irreversible one.

Peace and security

The implications for peace and security similarly reach far beyond Ukraine and are destabilising the geopolitical environment across Eurasia and globally. China is watching European and US responses to the war very closely. Beijing may exploit the European and US focus on Ukraine to reinforce its position in the South China Sea and Taiwan and to further challenge US power in hotspots across Eurasia, such as the Western Balkans and Pakistan. Potential NATO expansion to include Sweden and Finland and greater European defence spending will also exacerbate China’s concerns about US military reach in core strategic areas.

Overall, the war may embolden China to challenge the US-dominated rules-based international order more openly by using China-initiated regional forums to garner support from like-minded states. Greater European defence spending and NATO expansion will also fuel Russian paranoia and may affect the course of the war in Ukraine. The conflict has also increased the risks associated with both tactical and strategic nuclear warfare, which are now higher than at any point since the end of the Cold War.

Changing financial and commodity flows

And yet as in any crisis, there are opportunities as well as risks. Countries, companies and other actors can benefit from changing financial and commodity flows, legal or illegal. The UAE, for example, may take advantage of sanctions for financial gain as many wealthy Russians seek to move their cash overseas. Similarly, volatility in commodity markets may create opportunities for countries like Qatar to capitalise on export restrictions on Russian fossil fuels as demand for alternative sources of LNG and other fuels surges.

Organised crime

Prior to the conflict, Ukraine was a target and transit hub for human trafficking and other illicit activities such as drug and arms smuggling. As organised crime groups are adapting to conflict, the conflict may also open up new opportunities for human trafficking and illicit commodity flows through the Western Balkans and countries like Poland, where many refugees crossed the borders into the EU. Reports of pimps and sex traffickers targeting refugees emerged early on in the crisis.

China's response and geopolitical shifts

To understand and manage the risks the Ukraine conflict is creating, it is not enough to simply look at the risk perceptions of stakeholders whose values and priorities are broadly aligned with our own. Take, for example, European and US sanctions against Russia. While the US, the EU and their allies view sanctions as a legitimate means of punishing Russian aggression and undermining its capacity to carry on the war, while discouraging such behaviour in others, China, conscious of its own vulnerabilities, has vigorously opposed their use.

In response to the most recent sanctions on Russia, China’s Vice-Foreign Minister, Le Yucheng, reiterated that ‘China has all along opposed unilateral sanctions that have neither basis in international law nor mandate of the (United Nations) Security Council’. China has sought to protect its own financial system from US overreach by introducing alternatives to SWIFT and RMB internationalisation. China may see the war as an opportunity to garner support for its ambition to reform the global financial system from like-minded countries concerned about their own exposure to potential US actions. If so, it will be a good example of how response to a threat in one system generates unintended consequences across others based on different risk perceptions.

As our emerging analysis illustrates, the Russian war in Ukraine is creating cascading risks that are destabilising systems we have long taken for granted, and leading to geopolitical shifts not seen since the Second World War. To understand and manage these emerging risks, it is critical to look beyond food and energy systems, because the consequences of the war on other systems are even greater.