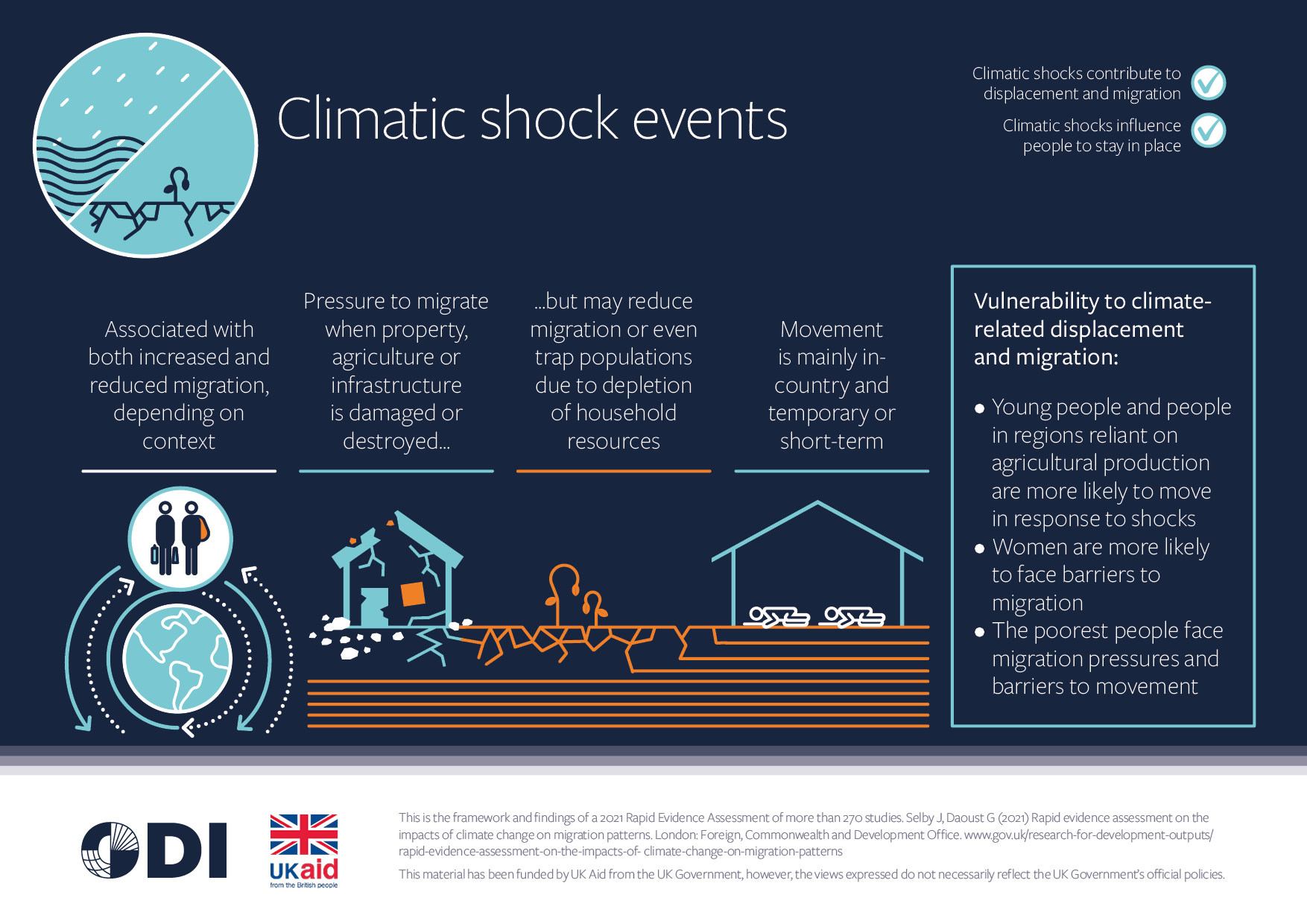

Migration and climate change are intersecting on the agenda for the first “Africa COP”. However, only half the story is being told: how climate change impacts drive migration and displacement. Evidence shows this is a complex area but central to climate justice.

The other half of the story needs to be told too: the opportunity for migrant workers to help deliver net-zero transitions and climate resilience. So far, this message of hope goes largely unheard in the climate negotiations.

The Paris Agreement and the Glasgow Climate Pact highlight the need for creation of quality jobs and a just transition of the workforce – but the focus has often been on workers in existing, high-carbon sectors. They also add migrants to a long list of groups imposing special “obligations”. These are partial narratives that cast migrants only as victims, and narrow our vision of just transitions to meeting the needs of fossil fuel workers. The climate accords thus miss the chance to recognise migration as a flexible tool to fill skill and labour gaps in climate aspirations worldwide, alongside measures like green skills development and investing in youth.

ODI’s pioneering research highlights how, from Democratic Republic of Congo to Bangladesh, and from Malaysia to Colombia, there are opportunities to support low-carbon transitions with migrant workforces. A joined-up, green approach to labour and migration policy could create new jobs with better working conditions; provide and foster valuable skills that stimulate productivity across the economy; and improve both local and global environments through tackling pollution, emissions and resource inefficiency.

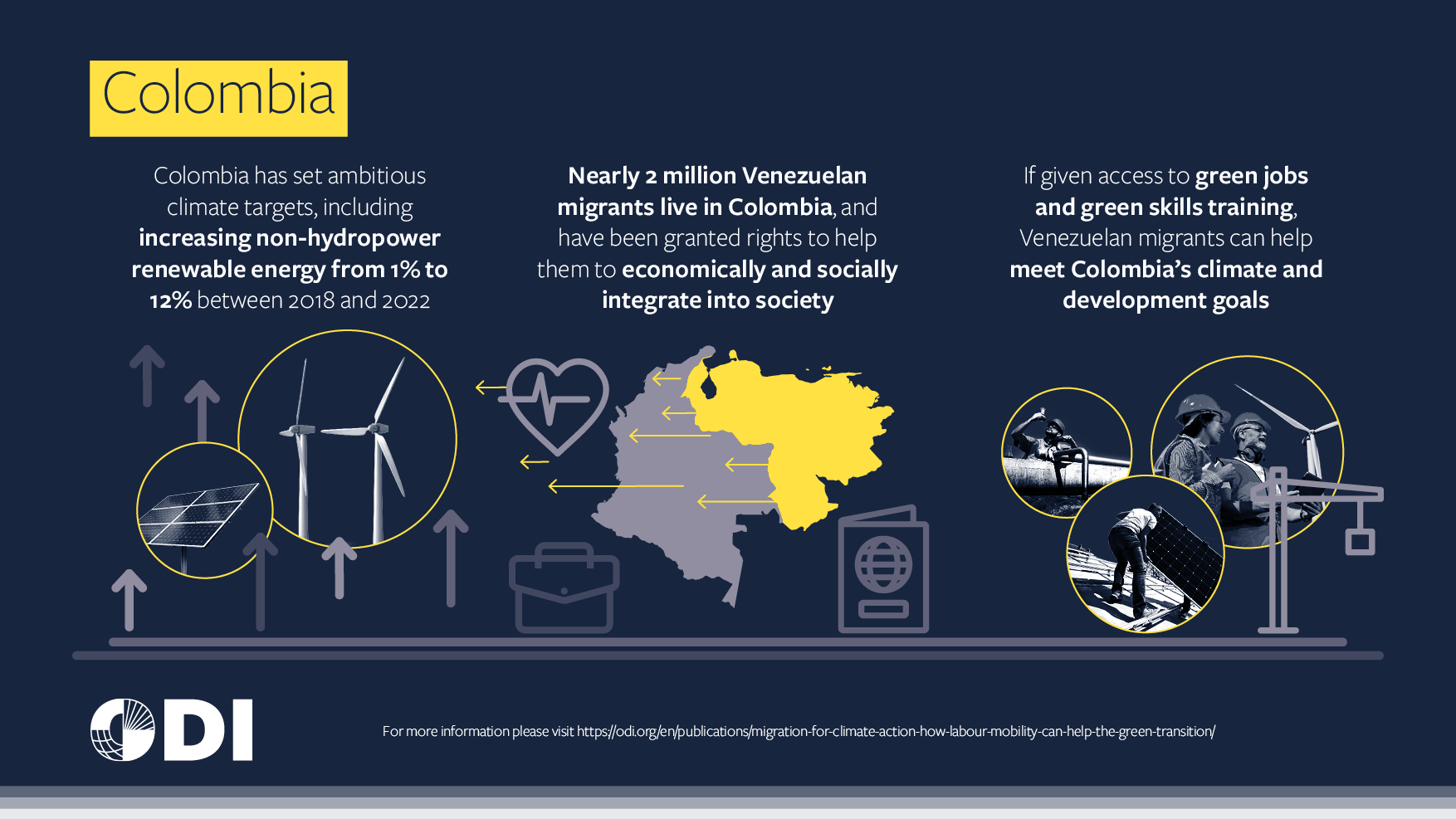

In Colombia, for example, two discrete national projects could reinforce each other: integrating workers from among approximately two million Venezuelan refugees and migrants into the economy; and reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by more than half by 2030. With a new president and top team recently taking office, there is renewed determination to shift the economy away from fossil fuel extraction. With access to green jobs and green skills training, Venezuelan migrants could contribute – alongside Colombian workers – to rapid transformation towards a low-carbon economy, including by delivering clean energy and nature-based solutions.

Economic logic is not enough, by itself, to get policy-makers using migration as a positive force for climate action. The politics of migration, climate action, and labour markets are all fraught and must be navigated carefully.

In the UK, as the Government searches for supply-side economic measures to grow the economy in the face of the country’s longest recession, and ways to translate lofty climate change ambitions into action, labour migration is an obvious answer. For example, the Government wants to increase the number of heat pump installations twenty-fold by 2028. Even this, which may not be sufficiently ambitious, would need a thirty-fold increase in heat pump engineers – reaching 27,000 by one estimate. UK media coverage and political statements around migration are currently polarising. Nonetheless, the arc of public opinion is smoother, remaining receptive to using immigration to address labour shortages.

Even as we work to amplify the positive story on the potential of migration for climate action at COP27, it needs to be heard beyond the climate accords. Labour, interior, education and foreign ministries all have a role to play in creating the green workforce of the future, with migrants recognised as part of the solution rather than the problem. Key priorities include to recognise qualifications across borders and amplify skills transfer efforts in a way that includes migrants in both origin and destination countries. Circular migration pathways, skill and talent partnerships, and student exchanges are all tangible mechanisms, with a growing number of real-world examples.

The final note of optimism is the promise of the migrants of tomorrow. Young people – often keenest both to move and to lend their energy to climate action – are the central narrators and players in this story. When developing solutions, youth, including voluntary migrants and displaced people, must be at the heart of climate and environmental action, such as waste collection and recycling, nature-based solutions, regenerative agriculture, clean energy installation, building retrofits, and the construction and operation of mass transit. Training programmes, the private sector, and unions must actively explore innovative skills and training schemes for young people between places of origin and destination, with a focus on upskilling for jobs of the future and advancing the low carbon transition.

YOUNGO – the official youth and children constituency of the UN climate convention – has a tremendous presence at COP27. Moreover, COP27 takes place on the world’s youngest continent, where the median age is 20 and three-fifths of the population are under 25. The demand for better jobs and safer futures must be heard loud and clear. Governments can meet this demand by coordinating labour, migration and climate policy – if they have the courage to do so.