Global climate targets require an unprecedented level and speed of transformation to decarbonise existing sectors, build new ones, and adapt to the impacts of climate change.

Climate change also forces people to move. Yet governments and businesses have overlooked how migrants can contribute towards a low-carbon, greener future.

To do so, they must remove obstacles, create incentives, and foster pathways to harness the potential of migrant workforces to support green transitions.

Governments and businesses must coordinate efforts on the green transition with migration and skills policies across four interlinked areas.

We identify four key opportunities that can support green transitions with migrant workforces. These are:

1: Support green transitions with migrant workforces

2: Make existing jobs for migrants green and decent

3: Create new green jobs for migrant and host workers

4: Foster green skills for current and future migrant workers

We look at four case studies of migration from around the world: in Bangladesh (internal migration); from Venezuela to Colombia; from Indonesia to Malaysia; and from China to the Democratic Republic of Congo, to see how these four opportunities can be harnessed.

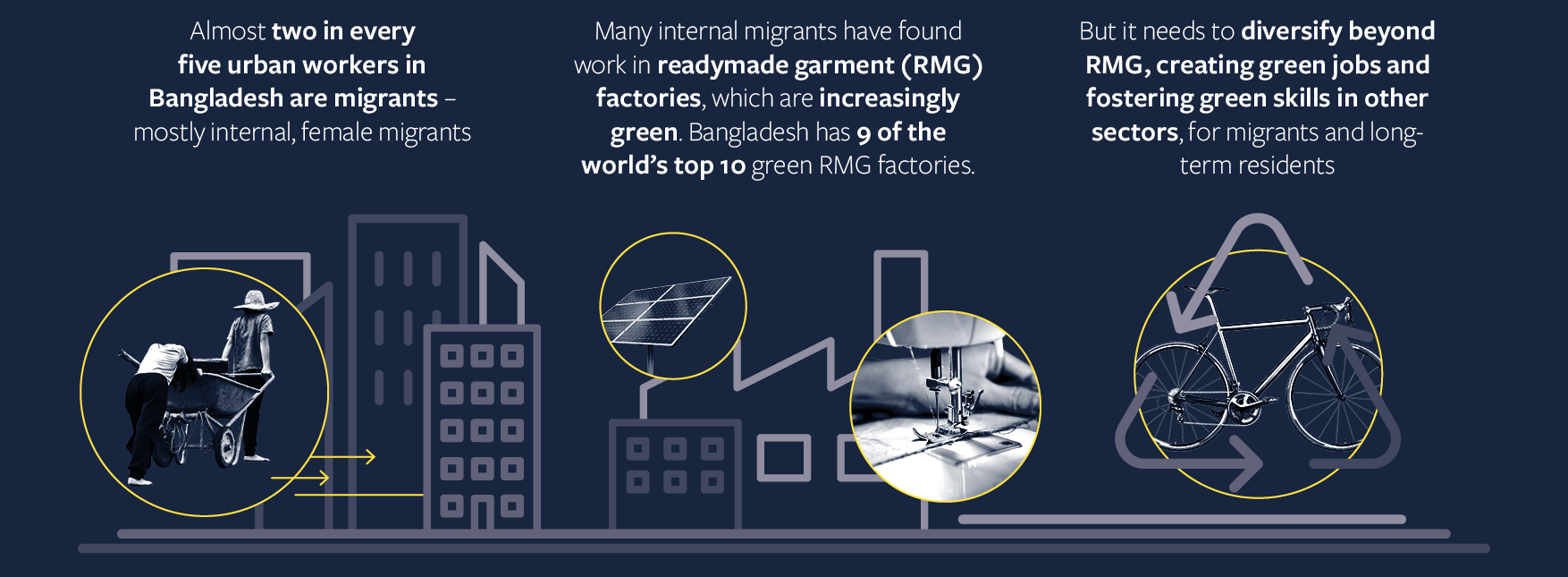

Case study one: growing green jobs and skills for internal migrants in Bangladesh

For Bangladesh green skills development and job creation can provide opportunities for internal migrants and others in rapidly growing cities, while also improving economic resilience and sustainability.

In Bangladesh’s cities, nearly two in five workers and nearly half of female workers are migrants, mainly from rural areas of the country. As the urban share of the population swells from a third to nearly two-thirds by 2050, and environmental degradation increases, there is an urgent need for green jobs.

The challenge for cities is to create green jobs in existing and future growth sectors – for migrants, long-term city residents, or young people – while advancing green skills for all. A multi-sector approach to green industrialisation can also help Bangladesh’s economy become more resilient by diversifying beyond readymade garments (RMG), which currently makes up over 80% of exports, while reducing environmental vulnerabilities.

Green pathways to develop jobs and skills exist across formal and informal sectors, as well as future growth sectors. In formal sectors like RMG, up to 85% of the 4 million RMG workers are migrants, and many are poor, less educated women from rural areas. Bangladesh has 9 of the top 10 green-certified RMG factories in the world, but while the sector has managed to increase skills through on-the-job training, Bangladesh needs to invest in green skills.

A more comprehensive approach, including skills development via technical and vocational education and training (TVET) institutes, could position Bangladesh to better meet the global demand for sustainable fashion. By investing in relevant skills such as textile collection, sorting and repair, firms can also better retain workers, and therefore cut costs.

Informal sectors such as waste management and recycling employ up to 77% of workers in Bangladesh’s cities, many of whom are rural-urban migrants. With up to 63% of solid waste going uncollected in cities, there is scope to expand employment. Exploitation of manual waste pickers, who are mostly impoverished and uneducated women and children, is rife.

Building awareness and hazardous material management skills among waste pickers and sorters — while introducing circular economy practices for waste coordinators and distributors — could improve environmental outcomes and be part of a wider package of reforms to improve worker safety and remuneration.

Light engineering (manufacturing) a priority future growth sector, could see exports grow from less than $500 million to $9 billion per year, creating many jobs for migrants and city residents. Bicycles exemplify this opportunity: Bangladesh is already the third largest exporter to the EU. Employment opportunities cover a range of skills, from welding and machine operation to design and process engineering.

There is scope to build greener knowledge and practice from the ground up. As with RMG, an on-the-job approach to skills development needs to be matched with technical and vocational education and training in both rural and urban areas.

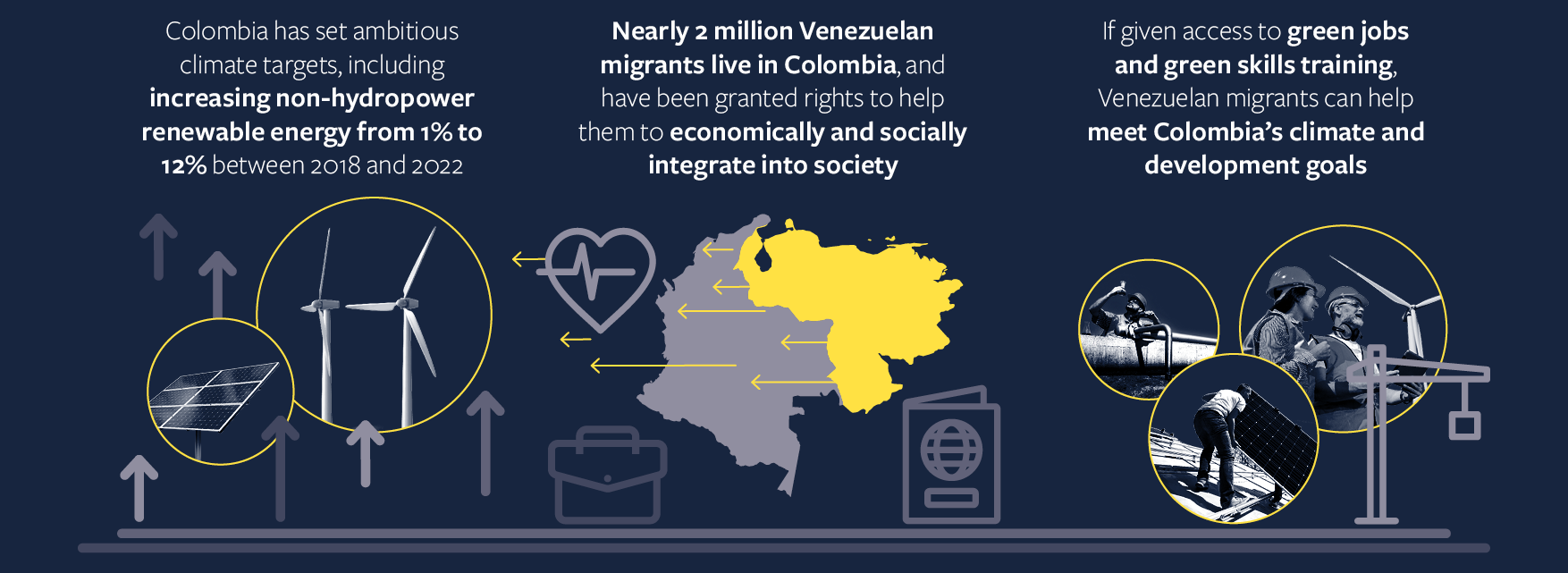

Case study two: Venezuelan migrants to drive climate action in Colombia

Colombia has shown strong climate ambition in recent years. Colombia’s national climate plan pledges to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 51% compared to business-as-usual levels by 2030, and its Low Carbon Development Strategy aims to reduce emissions across different sectors, while contributing to broader social, environmental and economic goals. As part of its decarbonisation plans, Colombia has committed to increase its share of non-conventional renewable energy (i.e. excluding hydropower) from around 1% in 2018 to 12% by the end of 2022.

Colombia has also shown exemplary leadership by welcoming nearly two million Venezuelan migrants by issuing work and stay permits, extending access to health, education, and social programs, and protecting vulnerable populations. There have however been challenges integrating Venezuelan migrants into the labour market. A significant barrier is the recognition of educational and professional credentials: only 10% of Venezuelans in Colombia reported having had their professional credentials recognised as of October 2020. Moreover, there is a lack of job opportunities.

Given Colombia’s ambitions to economically integrate Venezuelan migrants and its climate plans, there is an opportunity to employ migrants and locals alike in the expanding renewables sector.

Some of the regions with the highest potential in terms of wind and solar, such as Atlántico and La Guajira, are also home to the largest number of migrants in Colombia, including the very high number of migrants from Venezuela.

Although many Venezuelans have skills mainly relevant to fossil fuels, they also possess many skills in construction, which could be transferable to wind farms, solar energy parks and other large projects. There is also scope for migrants to work in conventional renewable energy sectors, such as biofuels, hydropower and biomass, where most of the current jobs are.

There are already commitments to speed up degree recognition and skills certification, alongside improving access to job training programmes. There is now a need to further invest in green skills training for locals and migrants, with a view to supporting gender equality goals. International financing can be used to develop an economic integration strategy for migrants in rural areas, in line with the country’s energy transition and economic inclusion targets.

Key next steps include skills surveys and fast-track credential recognition, specialised job fairs and efforts to match skills with potential employers. Employers in the energy sector likely do not have information on the education and skill set of migrants, and targeted support will be required to match workers to employers. Given job opportunities are concentrated in a small number of departments and municipalities, partnerships with local authorities will be critical, with support from businesses and other key stakeholders.

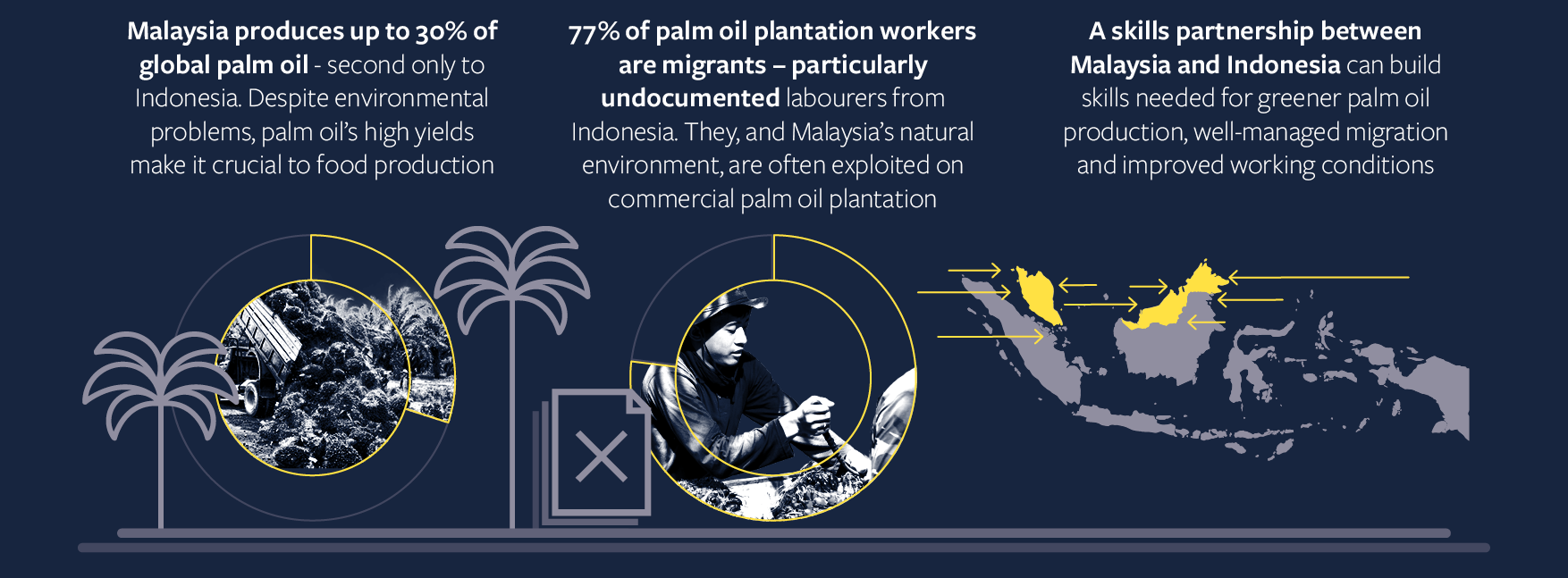

Case study three: palm oil production and migration in Malaysia

Palm oil production in Malaysia and Indonesia is responsible for at least 1.2 % of annual global greenhouse gas emissions. It is also environmentally destructive and a serious threat to biodiversity, including species such as the iconic orangutan.

Both emissions and biodiversity loss are driven by the expansion of palm oil cultivation, mainly at the expense of virgin forest, from just over 1 million hectares in 1980 to nearly 6 million hectares in 2020 and compounded by the application of pesticides. This expansion is the result of growing global demand for vegetable oils for consumption, biodiesels and consumer goods, including soaps, cosmetics, and cleaning products.

In Malaysia, palm oil plantations depend on exploitative labour practices, particularly of illegal Indonesian migrants. Malaysia’s immigration system is poorly designed and expensive for migrants and their employers. Registered migrants can only stay for three years and are tied to a particular employer. Migrants who become ill or pregnant are immediately repatriated. Up to 70% of migrants are estimated to be undocumented. They face poor pay and have few legal protections including against dangerous working conditions. Around 72,000 stateless children of undocumented migrants are thought to work on plantations.

There are currently no alternatives to palm oil. Palm oil makes up 35% of vegetable oils consumed annually. Its predominance is explained by its high yields, which are ten times higher than the next best vegetable oil (sunflower). Replacing palm oil would require around 50% of the world’s agricultural land.

The only viable solution is to improve the environmental sustainability of palm oil. This would require improving yields, decreasing waste, and managing pollution from waste products.

A global skills partnership which makes skilled migration more beneficial to destination and origin countries, and migrants themselves, can contribute to the greening of palm oil production. The destination country – in this case Malaysia – would train potential migrants in their country of origin, Indonesia. This both benefits Indonesia, by increasing its human capital, and Malaysia, by improving the sustainability and productivity of its palm oil sector.

A successful global skills partnership will require an improved recruitment process and a fully integrated skills development vision. National governments and the private sector will be essential to ensure that migrants acquire the right skills.

The Malaysian and Indonesian government must also determine a cost-sharing arrangement for any training provided. These types of partnership are of growing interest to the international development and migration community – as are the climate implications of agricultural production – and so may also attract donor funding.

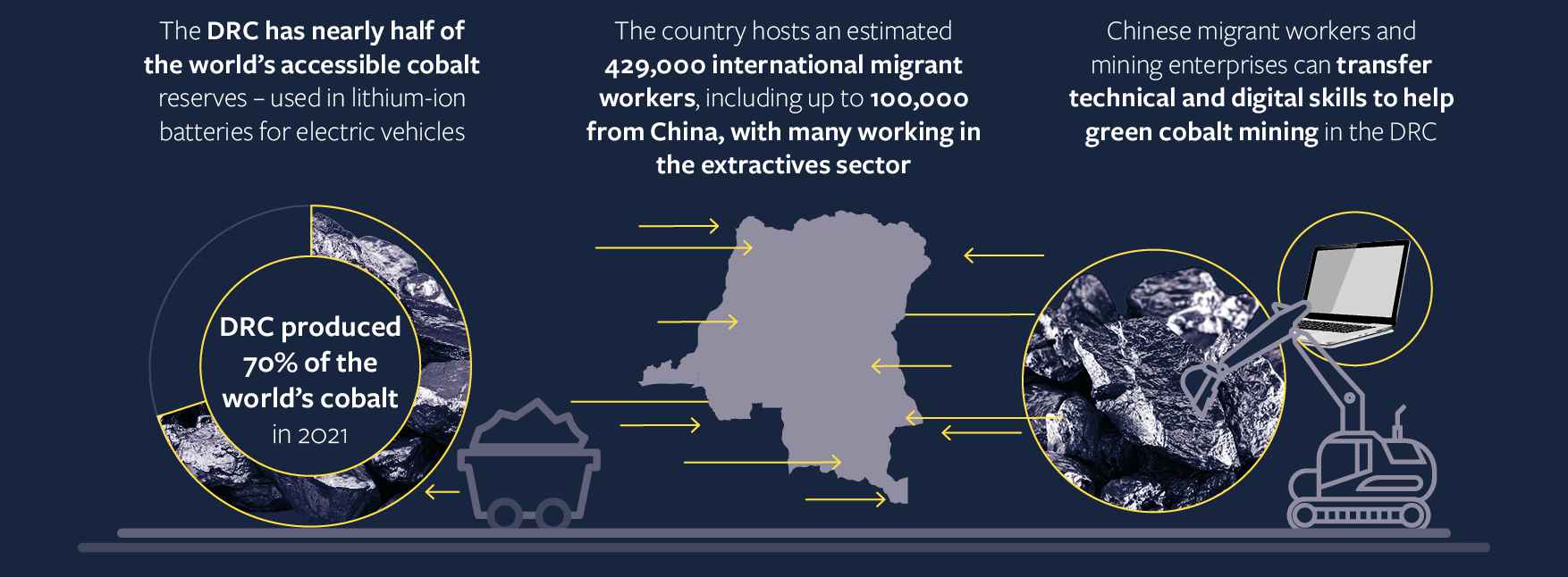

Case study four: cobalt production for lithium batteries in the DRC

The Democratic Republic of Congo’s (DRC) rich mineral reserves sit at the heart of the global e-mobility revolution. The low-carbon transition to electric vehicles is causing soaring demand for cobalt, which is a crucial component of lithium-ion batteries.

The DRC – which is responsible for 70% of global cobalt production – is the only country able to satisfy this increased demand. However, the sector requires international exchange of skills to ensure the industry develops in a green and sustainable manner with broader benefits for the country.

The huge appetite for car batteries has already caused two periods of soaring prices, so-called ‘cobalt crunches’. These have brought a wave of international investment to the country. This has the potential to see the DRC emerge as a prosperous ‘electrostate’, an economy powered by the opportunities of electrification and renewables. However, the sector is marred by poor working conditions, human rights abuses and low environmental standards.

Migrant labour plays an important role in supplying workers to African mining operations, which are often located in isolated and sparsely populated regions.

Today, the country hosts an estimated 429,000 international migrant workers, both from within Africa and outside the continent. Up to 100,000 of these workers are Chinese, who have mainly been attracted by the cobalt and copper industry.

Chinese workers, from mining provinces such as Shanxi, are present throughout the industry as entrepreneurial merchants, dealers and traders, in semi-industrial mining operations or as highly skilled executives, technicians and engineers. They play an invaluable role in transferring technical know-how to domestic workers in the DRC and other African countries. It is common for migrant workers to assist with start-up and provide training and education to local employees, which is often unavailable domestically.

These activities are partly the result of conscious corporate social responsibility efforts to improve skills among domestic workers. Skills transfer has also been a central part of China’s Belt and Road Initiative. However, where regulation is non-existent or poorly enforced, foreign investors, including Chinese firms, can make limited contributions to skill development and can lock-in dependencies on foreign human capital.

There is great potential to harness Chinese migrant workers to transfer green skills to the DRC’s workforce. This includes specific technical and digital skills associated with responsible and smart geology, as well as improved environmental standards.

It is a priority to integrate more artisanal miners, who are still responsible for around a fifth of the DRC’s cobalt production but are poorly renumerated and are frequently injured or killed in mining accidents, while the environmental impacts are catastrophic. There are also opportunities to diversify skills for upstream activities such as battery manufacturing, as well as in non-mining sectors.

Going forward, international mining companies can pool resources to provide formal technical and vocational education and training opportunities and promote green skills. National and local governments can help by adopting stricter policies on skills transfer and providing fiscal incentives.

The Move Green initiative

One nascent initiative which uses migration to support the development of green skills and sectors is the Move Green initiative between Spain and Morocco. This video explains the main motivations behind setting up this initiative, its key aims, the initiative structure and what makes it unique.

For all referencing and sources, please refer to our report Migration for climate action: how labour mobility can help the green transition.