Cultural heritage plays a major role in shaping our identities, enriching our spiritual existence, providing social cohesion, and helping us to understand our history. But as the planet continues to warm, leading to more frequent and severe extreme weather and slow onset events, the impacts of climate change are leading to the loss and damage of cultural heritage.

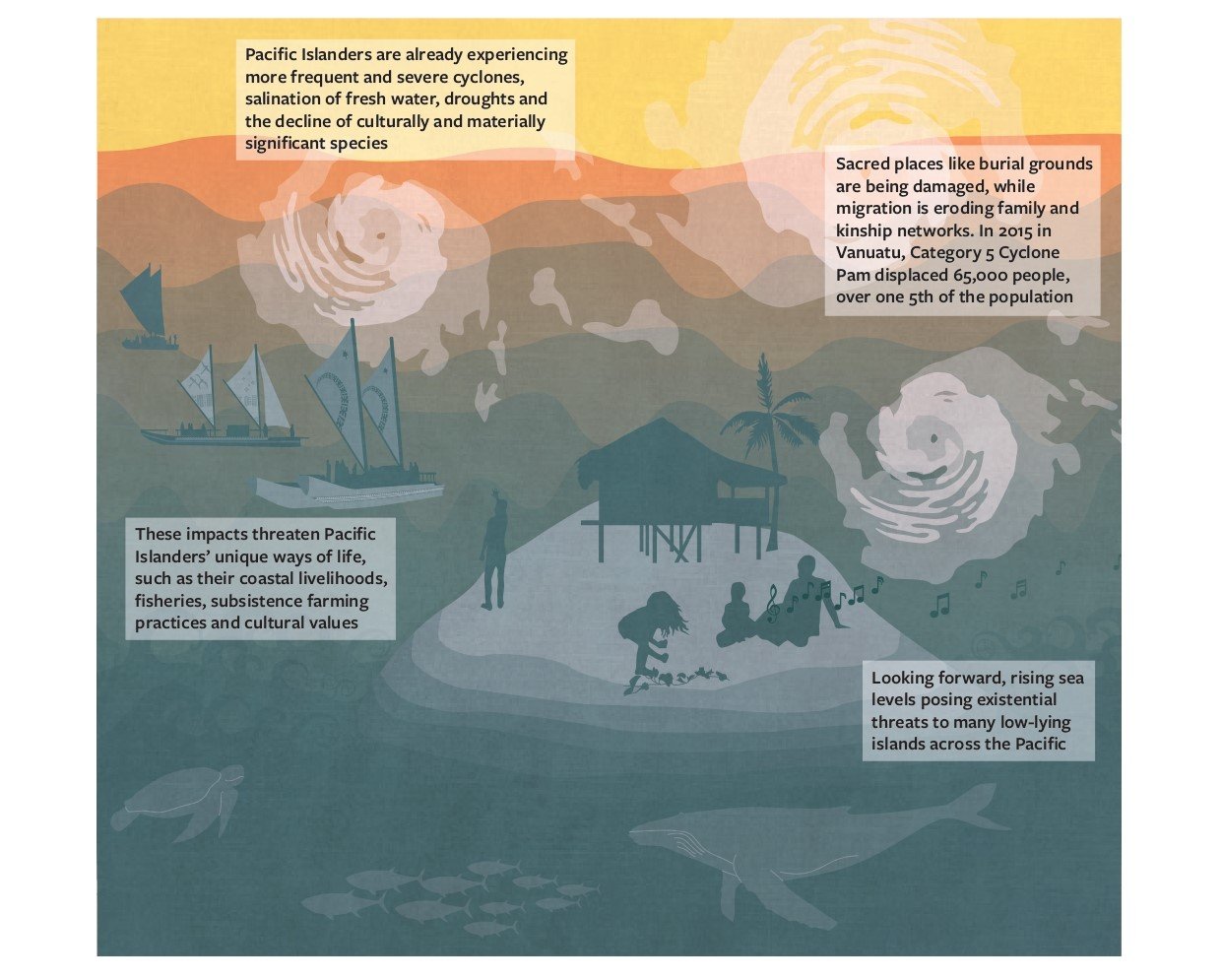

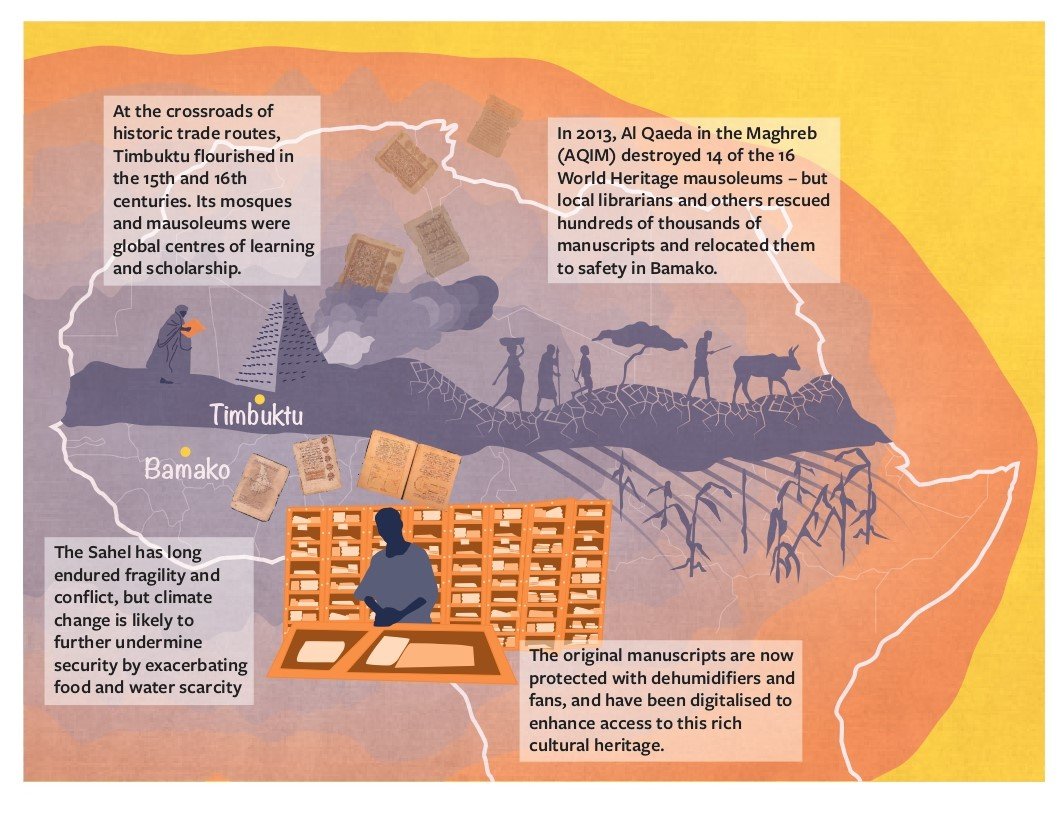

So how does this happen? What are the impacts of these losses, and how can we better respond to them? Our new research explores these questions. It draws on case studies from the Arctic, the Pacific, the Sahel and other regions to define, classify and measure the loss and damage of cultural heritage.

Loss and damage through a non-economic lens

In the context of the climate accords, ‘loss and damage’ describes the negative impacts of climate change that cannot be avoided due to insufficient mitigation and limits to adaptation. Loss and damage will have massive economic costs. They are often most acute in vulnerable countries – those least responsible for climate change. For decades, the Alliance of Small Island States (AOSIS) has highlighted the need to address loss and damage, but progress has been slow.

Loss and damage can be categorised into economic loss and damage, which refers to the loss of resources, goods and services that can easily be monetised, and non-economic loss and damage, which refers to losses and damages that are far more difficult to quantify or measure solely in economic terms. This may include loss of life, health, human mobility, territory, biodiversity, indigenous knowledge and practices, ecosystem services — and cultural heritage.

At 1.1°C of warming above pre-industrial levels, climate change is already threatening cultural heritage in varied and complex ways, including extreme weather events, acute disasters, slow-onset events such as sea level rise and droughts. Climate change may also indirectly lead to loss and damage to cultural heritage, for example through exacerbating water and food scarcity and thereby fuelling migration or conflict.

Types of cultural heritage

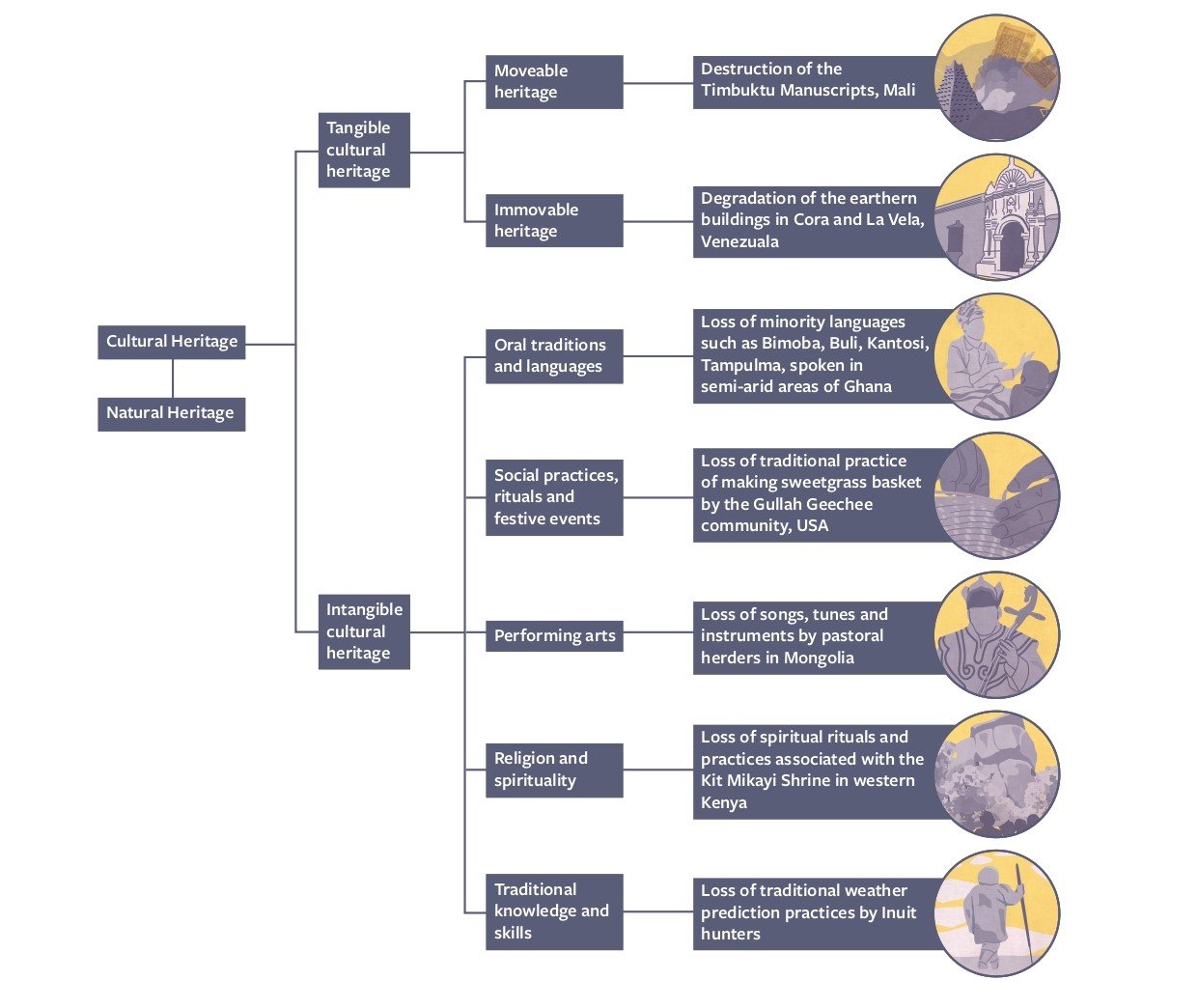

Cultural heritage can be categorised into tangible and intangible cultural heritage. Building on the categorisation of cultural heritage developed by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), the figure below provides examples of different types of cultural loss and damage, highlighting the nature of losses and damages that could be susceptible to the impacts of climate change.

What are the impacts of loss and damage to cultural heritage?

Cultural heritage plays a critical role in anchoring a community or country’s common identity. The loss of cultural heritage can rupture people’s individual and collective identity, as well as the social cohesion that comes from having common reference points and paradigms.

For some, cultural heritage is a vital connection to their past and a legacy for the future.

If the evidence or memory of cultural heritage is lost, all of humanity loses some ability to understand our past and pass on that richness to the future. While cultural heritage may be difficult to quantify in monetary terms, it is often tied to people’s livelihoods and incomes, so its loss and damage may have material and financial implications. These losses and damages can also have impacts on mental health.

How can we avert and minimise loss and damage?

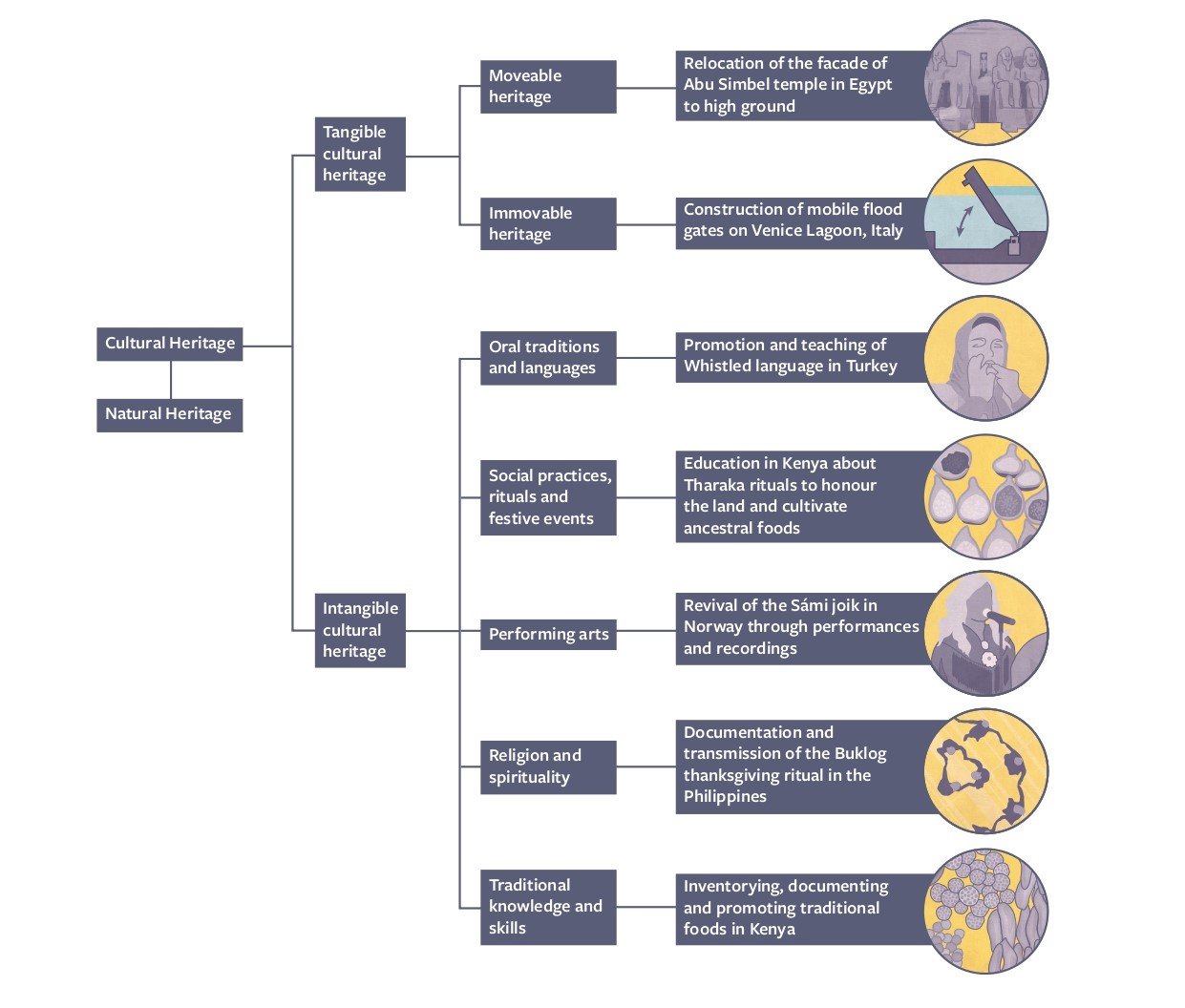

Beyond mitigation and adaptation, there is an array of examples from around the world where loss and damage to cultural heritage is successfully being averted and minimised. Take the field of heritage management. Heritage management systems may be adopted at the national or regional level or designed for a specific cultural asset, whether tangible (such as a single building) or intangible (such as an endangered language used across national borders).

There are highly sophisticated techniques for preserving vulnerable assets and restoring degraded ones that can be deployed in the face of climate hazards. These processes should bring together dedicated and specialised professionals with expertise in conservation, restoration, and stewardship to work with the local communities and authorities who have traditionally managed that heritage and who stand the most to lose.

The figure below provides examples to showcase the range of options available to avert and minimise climate-induced loss and damage to cultural heritage.

How can we address loss and damage?

Much loss and damage cannot be averted or minimised and therefore needs to be addressed. There is currently a lively debate around fair and appropriate ways to address non-economic losses and damages that result from climate change, including both the means of addressing them and who should be responsible for addressing them.

International experiences of transitional justice suggest five options to address cultural loss and damage:

(1) Restitution: restoring those affected to their original situation (or as close as possible) before the loss and damage occurred.

(2) Rehabilitation: redressing or repairing the harm done through the provision of social services such as healthcare, education or legal support.

(3) Satisfaction: symbolic measures to recognise loss and damage, such as truth-seeking, apologies or memorialisation.

(4) Material compensation: the provision of money or other benefits for loss and damage.

(5) Guarantees of non-repetition: commitments and measures to prevent similar losses and damages occurring in the future, such as codes of conduct, training or governance reform.

The five options can be used on their own or deployed in combination. It is important to recognise that, although material compensation is a discrete option, the other four options also entail costs. Also, these options vary in their relevance to climate-induced loss and damage to cultural heritage.

Final thoughts

Climate change induced loss and damage has so far mostly focused on economic loss and damage. Where non-economic loss and damage has been studied, loss and damage to cultural heritage has received less attention than other domains, such as the loss of lives and health.

With support from IrishAid, our new paper highlights the nature of cultural heritage loss and damage and some ways in which climate change may contribute to it. We also highlight that by learning from other sectors and adopting inclusive approaches, much more can be done to avert, minimise and address cultural loss and damage through a fair process for those most affected.