When Emmanuel Macron became president of France in 2017, he came with a clear ambition to modernise French aid. This vision is now captured in new legislation that was adopted in August of this year and which sets out the strategic framework for France’s development policy over five years and the financing required to implement it.

Introduction

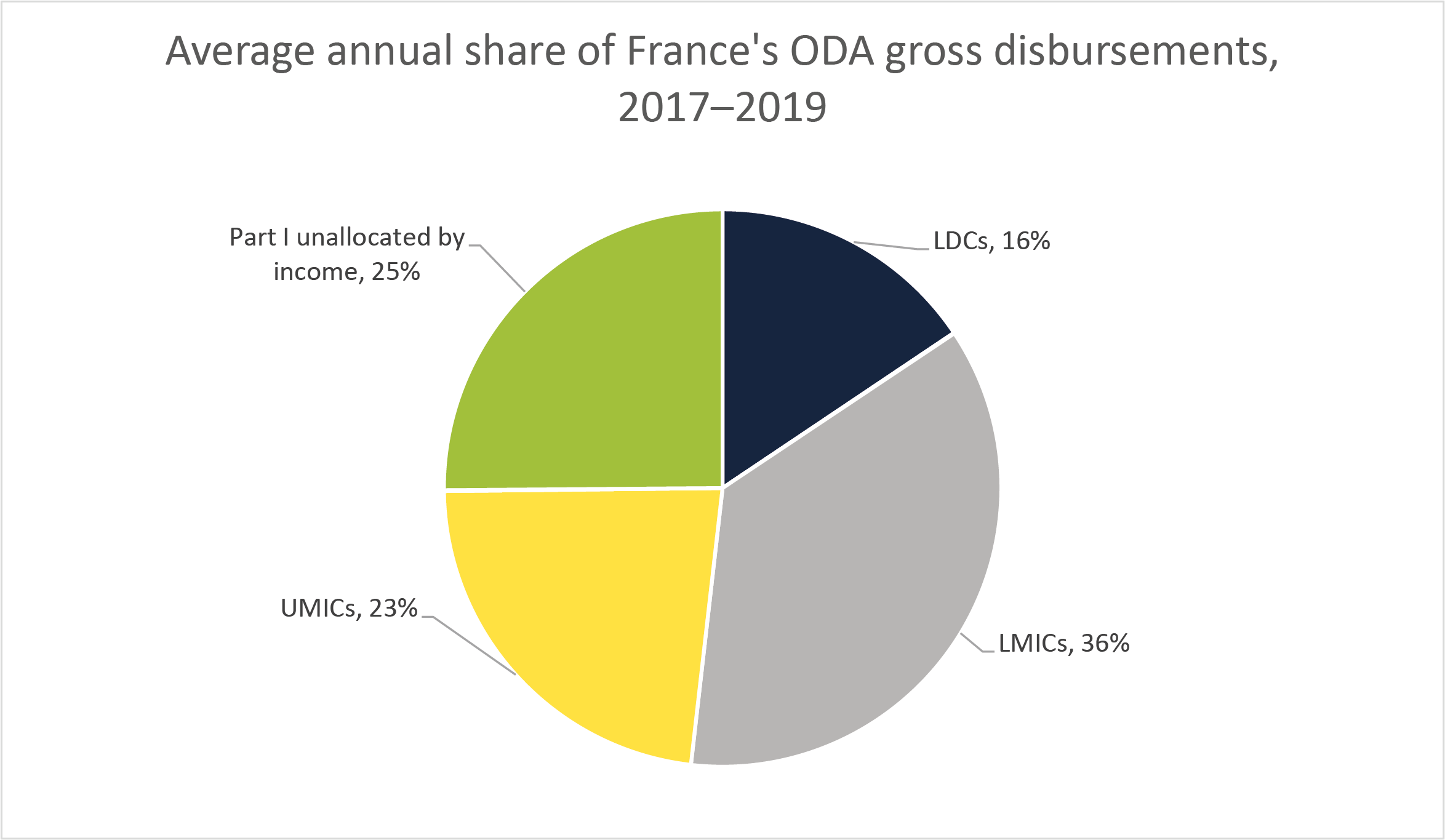

At the start of Macron’s mandate, France’s aid programme was characterised by a focus on Africa and Asia. Although low-income countries (LICs), mostly in sub-Saharan Africa, had been identified as priority recipients of bilateral aid, the majority of French aid went toward lower-middle-income countries (LMICs) and upper-middle-income countries (UMICs), a large share of which was in the form of loans. Despite some regular mentions of reaching the target of spending 0.7% of gross national income (GNI) on official development assistance (ODA) at the domestic and European Union level, France was far from that.

Figure 1

Reform of French aid under Macron’s presidency

The changes in French ODA since 2017 were driven by Macron’s vision for a modernised development policy. This vision was informed by a report on France’s development policy commissioned in 2018, which led to the passage of a new law in August 2021. Replacing its 2014 predecessor, the law sets out France’s development policy objectives towards 2025, and the dedicated resources to meet them.

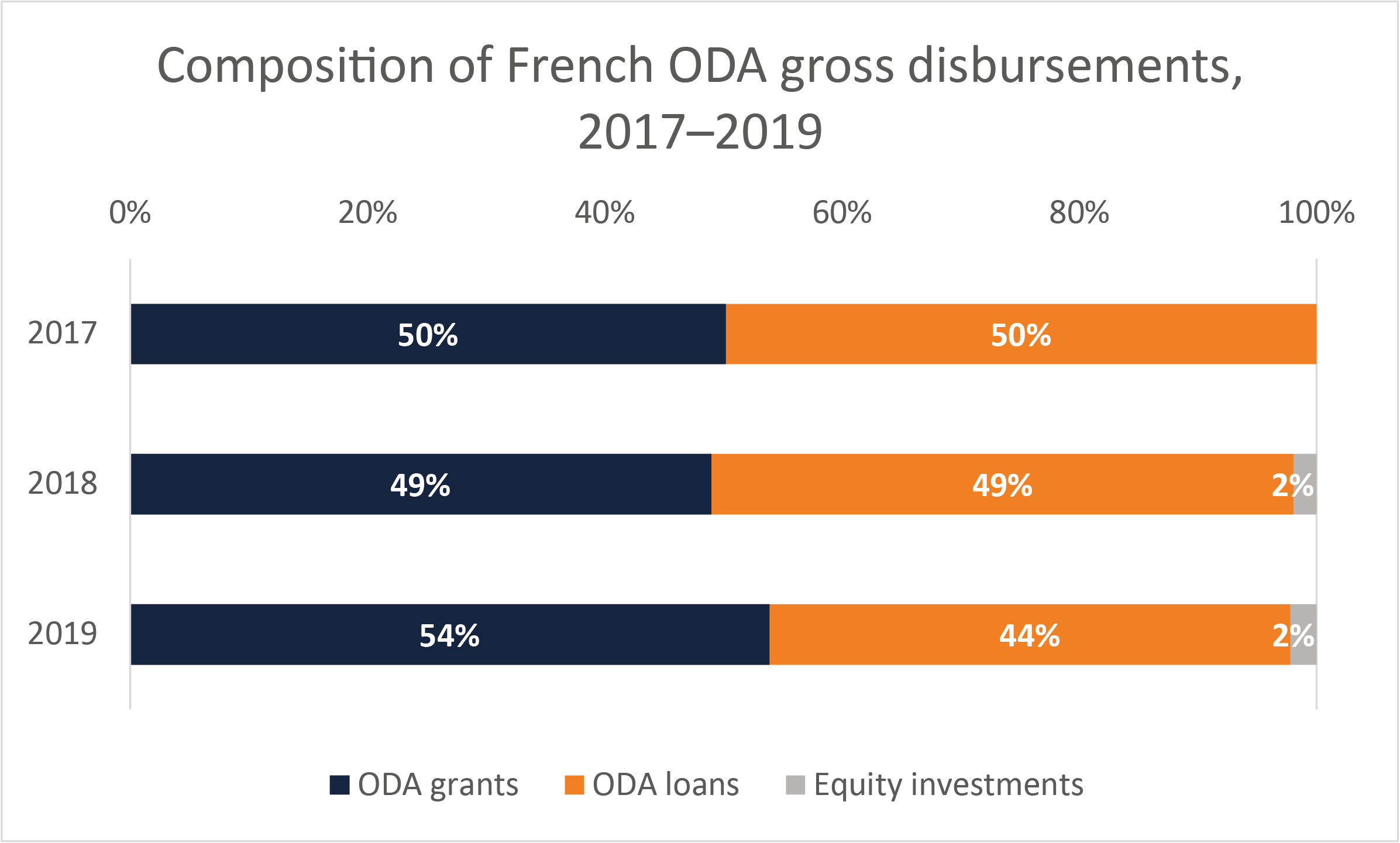

Figure 2

The new aid strategy introduces some noteworthy changes in terms of priorities and objectives, financing and governance:

- Striving towards the 0.7% target by 2025. The law includes a commitment to spending 0.55% of France’s GNI on ODA by 2022 – which is on track to be met – and to strive towards 0.7% in 2025. For the first time, it sets a multi-annual budget up to 2022 and proposes an indicative path towards 0.7% for the years 2023–2025, as the budgetary decisions will lie with the next set of parliamentarians and the new government in place after the 2022 elections. In practice, French ODA will meet the 0.7% target in 2021 due to record-high debt relief provided in that year in the context of the Covid-19 crisis, but it would be equivalent to around 0.51% if debt relief was not taken into account.

- Shifting toward more grants and fewer loans. The commitments in favour of LICs and priority countries have not in the past been backed by adequate financing. The new law seeks to address this by setting measurable objectives. Grants should make up 70% of bilateral ODA over the 2022–2025 period, and focus on LICs and priority countries. This will be achieved through a combination of increased ODA grants and ODA loans (counting only the grant element of those loans as per ODA accounting rules), with ODA grants set to increase more rapidly. By 2025, those same priority countries should receive 25% of France’s country programmable aid – up from an average of 14% between 2017 and 2019, according to Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) data. This may prove challenging for the Agence Française de Développement (AFD), the French implementing agency, which has a business model more geared towards loans. It will be interesting to see how the AFD adjusts to an increase in grant finance and investments in sectors that offer limited financial returns.

- Doubling the volume of aid channelled via CSOs. The law makes provision for a doubling of aid flows channelled via French and international civil society organisations (CSOs), as well as CSOs in recipient countries between 2017 and 2022. This increase, however, starts from a low base, as France disburses much less via non-governmental organisations (NGOs; 5% on average in 2019) than other Development Assistance Committee (DAC) members (15% on average).

- Increasing the share of bilateral aid. The law stipulates that bilateral aid should represent an average of 65% of France’s total ODA between 2022 and 2025. In effect, this will increase the budget of France’s implementing agencies, of which the AFD is by far the largest.

- Creating an evaluation commission scrutinising ODA and moving towards a more impact-oriented assessment of aid. Largely inspired by the UK’s Independent Commission for Aid Impact (ICAI), the new law creates an evaluation commission that will report back to Parliament. The aim of the commission is to encourage French aid actors to focus more on their impact on the ground.

- Aligning sectoral priorities with the Sustainable Development Goals. The set of priority issues is vast and wide-ranging, perhaps at the risk of losing focus. It encompasses the cross-cutting issues of climate, biodiversity, gender equality, fragility and conflict and human rights. It also includes thematic priorities around health, education, food security, water management and sanitation, sustainable and inclusive economic growth and democratic governance.

- Revising the governance of French development policy. The law revises and sets out the different levels at which decisions are taken. At the highest level, the Development Council chaired by the president brings together relevant ministers to agree on strategic decisions. The second level is an Inter-ministerial Committee chaired by the prime minister, which coordinates state actions, determines priority countries and takes decisions regarding bilateral and multilateral aid allocations, for example. The minister in charge of development is responsible for the implementation of these decisions. It is worth noting that no minister has development policy in their portfolio in the current government, so the role is split between the Minister of Foreign Affairs and one of their junior ministers, which seems at odds with the reform’s aim to clarify governance structures. In recipient countries, the law clarifies that the ambassador is in the lead and coordinates French development actors on the ground, putting an end to the ambiguity over whether the AFD country director or the ambassador is in charge.

Will the strategy boost France’s standing as a European and international leader in development?

It is fair to say that France is not starting from scratch – far from it. The latest two editions of the Commitment to Development Index ranked France second among 40 of the largest donor countries for its dedication to policies that support development in other countries, a ranking that is driven in particular by its investment policies rather than its foreign aid. With the new strategy, this score has the potential to improve as France looks set to continue on the same course with its investment policies in developing countries, while also seeking to increase the quality and quantity of its foreign aid. The reform should also improve France’s relatively low ranking on ODI’s Principled Aid Index, a score which suggests France is less motivated by the achievement of long-term development results than the use of aid to secure short-term national interests. At the EU and international level, France has been an important and vocal actor on a number of development topics, including innovative financing for development and mobilising funds at the multilateral level in the health sector.

So, if France is already an established international leader in some areas of development policy, what changes does this new strategy bring? The strategy takes France towards the type of aid agenda associated with the UK, the Netherlands and the Nordic states in the 2000s: an approach to aid that is less susceptible to criticism by NGOs as it steers away, to some extent, from high volumes of loans to middle-income countries and gives renewed prominence to social sectors and poverty reduction.

But the strategy on its own is not the whole story; it comes with leadership at the highest level, made possible by Macron’s interest in the sector, and then institutionalised in the new law. This puts France in a good place to exert influence and leave a mark on development policy beyond its borders. There are three areas where it can do that in the short term.

- At the EU level, France is assuming the rotating EU presidency for six months in January 2022. Although its agenda is not yet clear, Macron’s strong affinity for the Union is likely to mean a bold set of measures to come. The long-awaited EU–Africa summit will take place under the French presidency, offering another opportunity for influence.

- Beyond the EU, France has played a leading role in pushing the sustainability agenda through its development bank’s strong focus on climate and as the host of the Paris climate agreement in 2015. It continues to play a development leadership role at a time when few countries are speaking up for aid – for instance, through its involvement in the International Development Finance Club (IDFC), a group of 26 development banks working to promote and leverage development and climate investments, which France currently chairs. France also hosted the first Finance in Common Summit in 2020, bringing together public development banks to strengthen their partnership and reinforce their commitments in support of common actions for climate change and sustainable development. The Finance in Common Secretariat is headquartered at the AFD, in Paris, and is presided over by the AFD director general. Through those channels, France is actively pushing for a greater role for development finance institutions and for more coordinated action on climate and development issues.

- In the field of innovation, France was behind the creation of the airline-ticket levy and the Financial Transaction Tax designed to mobilise additional and more predictable resources for development purposes. It continues to foster innovation with the newly created Fund for Innovation in Development. This aims to provide seed funding for all types of organisations (research institutions, NGOs, governments, companies from all countries) to test new ideas, experiment and demonstrate what works so that successful development interventions can be scaled up.

These three examples illustrate a discernible push from France to play a leading and influential role in the EU and on the global stage.

Conclusion

Seen from the UK, the new reform brings the French aid system closer to the UK development agenda of the 2000s, and shows that the two countries’ development policies are now travelling in opposite directions. But at the same time, France retains some of its key donor characteristics with a well-established development bank and wide-ranging set of financial instruments. With these assets in hand, France appears to be in a good position to fill some of the leadership vacuum left by the UK. While France has committed to increase ODA volumes – for instance, by focusing on the poorest, providing more grants and focusing on impact – the UK has been cutting its aid budget, eliminated its cabinet-ranking Secretary of State for Development, merged the Department for International Development with the Foreign and Commonwealth Office and is making a ‘tilt to the Asia-Pacific’, implying less focus on fragility and poverty. France’s ambitions go beyond making the most of the UK’s aid decline as it wants to present itself as an alternative to other donors such as China. To do this, France is harnessing influencing opportunities through its EU presidency, active involvement in international processes and funding for the search for innovative solutions. A key question will be how much France’s new aid agenda, and the leadership role that could come with it, rely on Macron, and how sustainable they are if he is not re-elected at the next presidential election in Spring 2022, for which he has yet to declare himself a candidate.