The importance of justice, as an end in itself but also as an enabler of other development outcomes, is now well understood. But the justice gap is huge – globally, 5.1 billion people are deprived of justice. And there’s a financing gap: ODI has estimated the cost of a basic or ‘primary’ justice system in a typical low-income country to be just $20 per person per year. But this is unaffordable for low-income countries: even if they maximised their tax-take and allocated the same proportion to justice as member countries of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) do, low-income countries can afford less than half the cost.

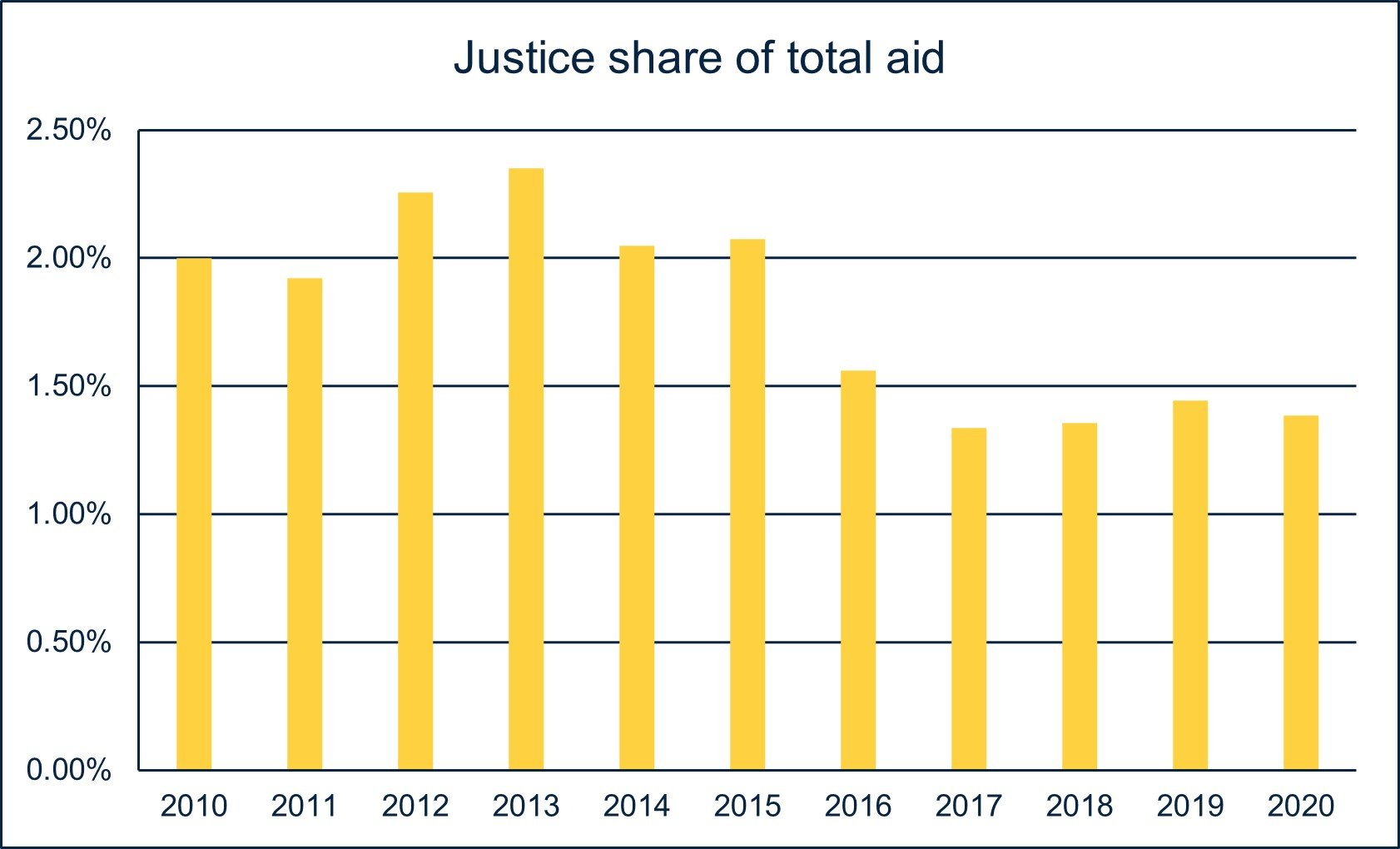

Despite the international community’s commitments to equal access to justice for all and to people-centred justice, latest aid data reveals that justice continues to be a low priority for donors. Total aid for justice currently stands at $2.9 billion a year, compared with $15 billion for education and $29 billion for health. Just 1.4% of aid goes to the justice sector – a fall from 2.4% seven years ago. Compare that to the priority that OECD countries put on justice at home, with 4% of their domestic budgets allocated to justice. The provision of justice aid is targeted at middle-income countries rather than low-income countries that are least able to finance the costs of basic justice systems themselves. This imbalance is likely to get worse due to the end of development aid to Afghanistan, a low-income country that has previously been the largest single recipient of donors’ justice efforts.

Taking people-centred justice to scale

With a global justice gap, and a widening financing gap to address it, it is more important than ever to ensure that justice finance is targeted to affordable and sustainable investments that deliver front-line justice services. The Justice for All Report stresses the need for justice services to start with people and their everyday justice needs. These services need to provide mechanisms to deal with people’s justice problems, conflicts, disputes and grievances. Sometimes, the formal justice system can resolve these kinds of issues, but more often than not accessible customary or informal forms of justice work best.

ODI’s research on taking people-centred justice to scale: investing in what works to deliver SDG 16.3 in lower income countries will highlight examples of effective people-centred justice services that have delivered results in an affordable, and therefore a scalable and a sustainable way. We’ll be looking at 10 examples of justice services across a range of lower-income countries that offer the potential to go to scale; explore how they’ve managed to provide effective front-line services at an affordable cost; and highlight learning points for future investments.

The focus of our analysis

The 10 examples of affordable, scalable people-centred justice in lower-income countries that we’ll be analysing are:

Bangladesh’s legal aid clinics were established and funded by a local non-governmental organisation (NGO). Their impressive frugal approach enabled them to develop a nationwide network of 400 offices responding to 20,000 clients a year. Yet, despite their efforts, most of Bangladesh’s population remained unreached – we estimate that this network only reached 1% of the three million people a year that need legal advice and assistance.

Community policing has been prominent in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). In remote districts of DRC, the police are the face of the state and the first point of contact for many justice problems. An international NGO is using an innovative results-based financing mechanism to increase police accountability to local people and improve performance.

Haiti has more than 11,000 people detained in prison awaiting trial – over 80% of the prison population. A donor-funded initiative giving prisoners free legal advice and assistance has tackled this problem effectively, and affordably. Our initial analysis of what happened in Haiti is in line with our previous work on affordable reduction in pre-trial detention in Malawi and Uganda and demonstrates that the global problem of pre-trial detention can be tackled cost effectively.

Following years of resistance, Kenya’s Judiciary embraced mediation as a way of reducing backlogs in the formal court system. While the initiative is still small scale (under 1% of cases are diverted), it appears to be a very effective mechanism, with a high return on investment.

A local NGO in Malawi with external donor support has a well-established network of community-based paralegals, who are providing front-line advice, assistance and mediation services to 130,000 clients at or below the $20 per case that previous ODI research suggests should be achievable in lower-income countries.

Sierra Leone’s government-funded Legal Aid Board also runs a network of community-based paralegals. Like Malawi, it’s a low-cost operation – $22 per case. The paralegals work across all types of legal need, and in one year supported 30,000 children to receive maintenance payments. We’ll build on our previous research on this initiative and dig deeper into their model to explore what it would cost to scale up to meet the legal needs for the whole country.

We’ll also be looking at other affordable and cost-effective front-line justice initiatives in other lower-income countries: Liberia, Rwanda and the Solomon Islands, and Uganda.

Some of these justice services have already gone to scale. Others have the potential to do so. Some are entirely home-grown and funded from domestic resources. Others are supported by external donors, and have been developed in partnership with international actors. What they all have in common is that they have had a measurable impact in addressing people’s justice problems, and with initial indications that they have done so affordably and sustainably, with realistic unit costs.

Contact us

This research is ongoing, with our final synthesis report due in September 2023 following a series of roundtable discussions with change-makers from lower-income countries, as well as with donors.

In the meantime, do feel free to contact Clare Manuel or Marcus Manuel directly with more examples of affordable people-centred justice services in lower-income countries with more examples of affordable people-centred justice services in lower-income countries. We’re keen to find and document as many as possible.