On 25 February, Nigerians are going to the polls in one of the country’s most uncertain elections. Online campaigns have generated attention for a number of reasons – from circulating disinformation to their role in the rise of Peter Obi, a new frontrunner with a large online presence. To make sense of what is taking place online, we investigate what is actually new – who are the influencers driving debates, where are the key fault lines, and how does this reflect the wider political context.

Nigerian Presidential elections are complex, taking place across the country’s various regional, ethnic, religious and economic divides. In 2023, there are three competitive political blocs and four leading presidential candidates. The incumbent All Progressives Congress’s, Bola Ahmed Tinubu is challenged by the People's Democratic Party’s Atiku Abubakar, the New Nigeria People's Party’s Rabiu Musa Kwankwaso and the New Labour Party’s Peter Obi. All have been involved in electoral politics before: Obi, Tinubu and Kwankwaso are former governors, Abubakar was Vice President, and Obi was Atiku’s PDP running mate in 2019. The candidates’ choices of running mate have only added to the high stakes ahead of this week’s elections: Tinubu’s running mate, Ahmed Shettima, like Tinubu is Muslim, but from the North East – like current President Muhammadu Buhari. The identities of candidates and their running mates are so important because of a crucial unwritten rule in Nigerian politics, whereby the Presidential seat rotates between the North and the South (known as zoning) every two terms, and running mates are often selected from a different faith communities and different geo-political zones.

Nigeria’s online (dis)information landscape

With an increasingly active younger electorate online, social media is a dynamic feature of political contest. Nigeria’s online community includes popular Nigerian influencers, journalists, ‘sponsored celebrities’, news outlets, activists, political figures and their advisors. While politics still invariably happens offline, online communications are gaining attention in political contests. The scale of the #EndSARS protest in October 2020, Twitter’s removal of President Buhari’s tweet in June 2021 and his subsequent banning of Twitter until January 2022 confirms Twitter as a space to contest political power. Disinformation campaigns have also featured in previous elections. In the 2015 election, foreign groups, Team Jorge and Cambridge Analytica, were involved in disinformation against then Presidential candidate Buhari. In 2019, supporters of both Presidential candidates, President Buhari and Atiku Abubakar, circulated false and inaccurate content.

The unpredictable 2023 Presidential contest heightens the stakes in Nigeria’s online civic space. Election-related disinformation has been described by certain media outlets as an ‘existential’ problem, and the presidential race as a test for democracy on the continent. Disinformation targets the four primary candidates but also electoral institutions, like the Independent National Electoral Commission. While Twitter remains a key space for political communications online, sharing of disinformation is also increasing across platforms, notably of content created on TikTok.

Equally, disinformation campaigns don’t necessarily win elections, as evident from Buhari’s win in 2015 despite the use of disinformation against him. Before overstating the significance of disinformation, understanding the information landscape is key: which influencers capture attention and how divisions unfold online.

What do the online information campaigns look like so far around the Nigerian elections?

To investigate Nigeria’s 2023 elections online, we collected over 600,000 tweets in the three months following the official launch of campaigns (September 28 to December 31, 2022), complementing initiatives in Nigeria that specifically investigate fake news and misinformation. We selected general election-related keywords and phrases for our query: “#nigeriadecides2023”, “#recovernigeria”, “recover Nigeria”, “take back Nigeria”, “#2023elections”, “2023 general elections”.

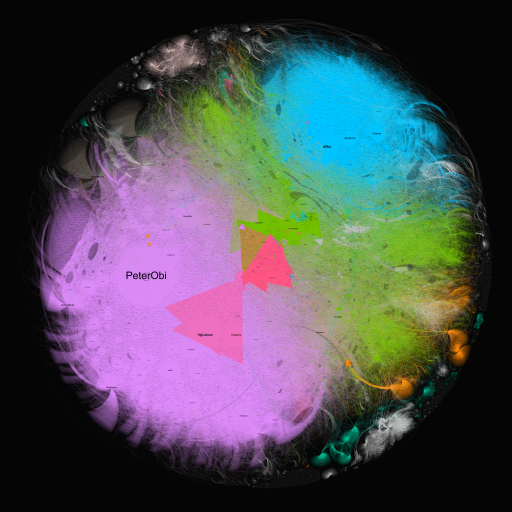

We examined interactions between users (e.g., retweets, comments, mentions) and the emergence of communities. Results are presented in the figure below. Each colour represents a community of users who tend to interact. We also examined underlying data to see which accounts tweeted the most, versus which had the most engagement.

Three distinct community clusters are apparent: Labour Party’s Peter Obi (Purple), Bola Ahmed Tinubu, All Progressives Congress (Green) and Atiku Abubakar, Peoples Democratic Party (Blue). Obi and his Obidient movement (supporters of Obi) are the most dominant. To confirm this, we isolated results for ‘#nigeriadecides2023’, removing keywords like ‘take back Nigeria’, a slogan taken up by Obi’s supporters. Here too, Obi’s account dominates.

An anti-establishment candidate to his supporters, Obi’s internet presence has shattered norms. Obi has shifted from outsider to frontrunner, with some polls predicting his victory. His popularity online seems to have been aided by some youth in the #EndSARS movement, rallied behind his call to “take back Nigeria” from an ageing political elite.

Focussing on the information environment also reveals new social media influencers, who are helping to make Obi prominent online. New influencers, almost all in Obi’s community, tend to position themselves in opposition to the longer-established political influencers, opinion leaders and news sources of the past, who today do not feature prominently. Some new influencers, like FirstLadyShip, AishaYesufu and SavvyRinu, became popular around the #EndSARS movement. Another, DavidHundeyin, is an investigative journalist in the UK, whose popularity appears linked to his exposés of candidates.

New influencers and accounts reveal a decentralised information ecosystem. While this has brought Peter Obi’s campaign to the fore, no single influencer account seems to dominate. These dynamics introduce new questions about the interests that underpin online communications: have the ‘old guard’ withdrawn from the online ‘influencer business’? Has the emerging Twitter community pushed them out to the periphery? One thing appears clear, the 2023 election is changing patterns of influence in campaigns online. Equally, despite this dynamism online, there is little evidence as of yet of online activity translating into electoral outcomes across Africa.

What’s next: Exploring the effects of disinformation within influencer networks

There are important concerns within Nigeria’s online election campaigns, specifically with the increasing scale of mis/disinformation. Evidence of sponsored disinformation necessitates close attention by regulators, social media platforms and fact-checking agencies to weaponised social media usage that capitalises on societal values, beliefs and behaviours.

Yet, disinformation is only part of the online information ecosystem. In Nigeria, attention to broader online debates helps to locate new citizen voices and sources of influence. The prominence of #EndSARS influencers indicates new opportunities for some young people’s engagement in political debate, which may complement and/or extend beyond the vote. For those concerned with the future of electoral competition, it is important to acknowledge both harms and opportunities for voice.

Looking at the online information ecosystem can also provide evidence to help protect against a shrinking civic space online. Disinformation has become a rationale for some to argue and implement internet shutdowns, arguably leading to premature shutting down of online spaces. Social media companies and researchers can help to make the online information ecosystem more transparent, by providing greater visibility to diverse voices and moderating harmful content. In considering future electoral competition in Nigeria, which is increasingly digital and dominated numerically by a young electorate, paying attention to who and what has influence in a dynamic and uncertain political landscape will only become more important.