Promises to universalise access to education have a long history going back to Article 26 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948. The UN World Conferences on Education at Jomtien (1990) reaffirmed the core commitment to universalise basic education and the World Education Forum in Dakar (2000) pledged that ‘no country with a credible plan should fail to educate all its children for lack of resources’. Expectations for financing set benchmarks of ‘at least 4-6% of GDP and 15-20% of government budgets’ to realise universal access to education.

Since 1990, levels of public investment in education in many low- and lower-middle-income countries (LICs and LMICs) have plateaued at levels too low to deliver on promises. Despite much high-level advocacy and large amounts of aid, there is a financing trap that has meant many LICs and LMICs have failed to reach or exceed 4% of GDP and 15% of government spending for education. Many projections indicate that more than 6% of GDP and 20% of government spending is needed to achieve the goals set.

The argument for placing investment in education at the core of development remains persuasive, but the promises to address chronic underfunding have yet to be realised. The financing trap is becoming more acute in prospect. Global recession, post-Covid constraints on recovery and a diminishing appetite for external assistance to support education are creating downward pressures on resources. According to the World Bank, two-thirds of LICs reduced education spending during the Covid-19 pandemic.

The risk is that the pursuit of the desirable will undermine the achievement of the possible as fiscal realities collide with unrealistic expectations. A change in approach is needed with i) achievable targets tailored to country starting points, capacities and aspirations; ii) enhanced efficiency and effectiveness to manage costs; iii) accelerated development towards fiscal states that balance revenue and expenditure; and iv) greater insight into more and less effective modalities for aid and concessional financing.

Global financing targets and ‘mission creep’

Mission creep has greatly expanded the level of aspiration since international benchmarks for financing education were first announced. By the Incheon World Education Forum in 2015, the agenda for universalising primary and secondary schooling extended downwards to universal pre-school and early childhood care, and upwards to grade 12. Out-of-school children (OOSC) now include all those of primary and secondary school age. Half of the 244 million OOSC are between 15 and 18 years old and above the legal minimum age for work. Expanded access to technical and vocational education and training, progressively free higher education and increases in international scholarships are included. This year’s UN Transforming Education Summit has now added more commitments to equity, real increases in spending per student, more funding of marginalised groups, new investment in re-skilling and more access to lifelong learning.

The ‘financing trap’

The escalating ambitions of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) have not been accompanied by changes in the benchmarks for financing, or reflections on how more revenue can be raised. Financing traps occur when development policy commitments outstrip the resources available from domestic revenue and prudent borrowing. Levels of expenditure have plateaued at the same time as demand is rising. If levels of investment are persistently insufficient to finance commitments to service delivery, and levels of expenditure equilibrate around a central tendency over time, then a financing trap is evident in which means and ends are mismatched.

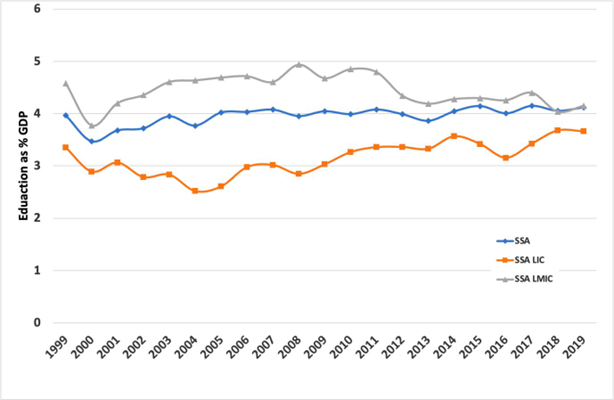

The empirical reality is that despite much advocacy and external assistance, the resources for educational investment in LICs have remained too small to achieve development goals. Data from sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) is illustrative. Investment in education relative to GDP has been fairly constant since 2000 (Figure 1). LICs in SSA increased the average proportion of GDP from below 3% to about 3.8%, while LMICs saw a peak approaching 5% around 2008/9 followed by a slow decline towards 4%. The long-term tendency is for convergence around 4% of GDP despite the need to reach much higher levels.

Figure 1: Education as a % of GDP

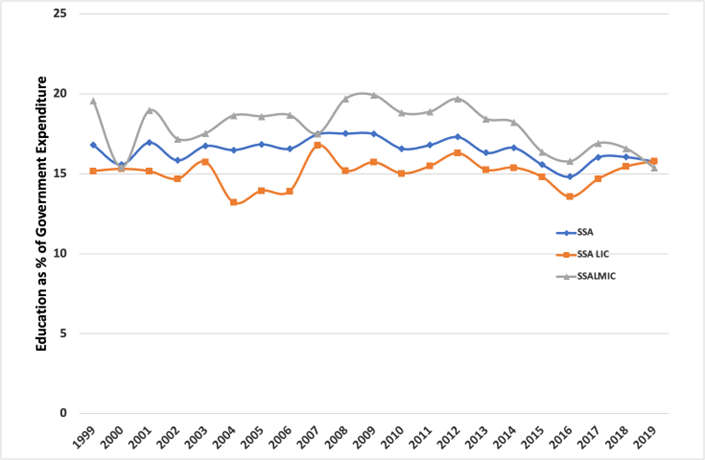

The first reason for static levels of expenditure is that on average, governments are not increasing the priority of education spending as a share of total government expenditure (Figure 2). This peaked at an average of 17% around 2008 and then declined slowly over the next decade. LMICs allocated a greater share of their expenditures to education than LICs. Both converged towards the lower limit of the UN benchmark of 15%.

Figure 2: Government expenditure on education as a proportion of total government spending

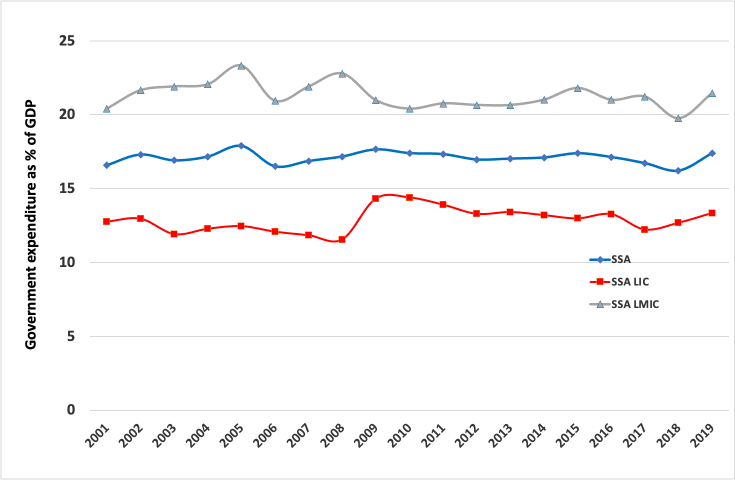

The size of total government expenditure mediates the value of the share allocated to education. The second reason for static levels of educational investment is evident in Figure 3. This shows that total public expenditure has fluctuated around 14% in LICs and just over 20% in LMICs. On average, the size of government expenditure relative to GDP has not changed.

Figure 3: Government spending as a percentage of GDP

In short, despite much advocacy, governments are not spending significantly more than 20 years ago despite rising expectations. Many projections demonstrate that countries with the demography and cost structure of SSA would need to allocate more than 6% of GDP to sustain the goals of SDG4. This would require additional recurrent financing in SSA of an additional $37 billion in LICs and LMICs for recurrent costs and an additional $15 billion annually to support investment in buildings and infrastructure.

If a country allocates 20% of public expenditure to education, and public expenditure is 20% of GDP, then education receives only 4% of GDP (20% of 20%). The average LIC currently allocates less than 15% of public expenditure to education and no more than 15% of GDP to total public expenditure. Reaching 6% of GDP would require at least 30% of public expenditure if total government spending was increased to 20% of GDP (30% of 20%). The necessary increases are implausible and are very unlikely to be achieved by 2030.

Aid will not fill the gaps. Total aid to basic education in SSA has been averaging about $2 billion a year compared to recurrent education spending of about $75 billion across all SSA countries. Both the volume and share for SSA have been shrinking.

What does this mean for governments and international partners?

Improving educational access and learning depends on addressing chronic underfunding. The ‘learning crisis’ is also a financing crisis where low learning levels are reinforced by under-funding. The current UN benchmarks for government education spending have not proved achievable.

Ways forward include four initiatives:

- Review goals and targets, and tailor to system-specific capacities, fiscal realities, plausible timelines and development priorities. There is a strong case to revisit commitments at national and international level so that they are calibrated to reflect achievable outcomes and assured streams of domestic and international financing that result from national policy dialogue and priorities. A starting point is to cluster systems in terms of current status and spending levels and profile costed pathways to sustainable goals. This process should be permissive of equifinality (different pathways to similar goals) and multi-finality (different outcomes).

- Enhance efficiency and increase effectiveness based on new evidence and past experience located in context and linked to costs. The opportunities will vary depending on the specifics of systems. Options include, but are not limited to, managing the flow of learners through entry, progression and completion of educational cycles; addressing the causes of dropout of different kinds; identifying and acting to reduce ‘silent exclusions’; increasing resonances between system outputs and demand from labour markets and livelihoods; more efficient recruitment, training and deployment of teachers; enhancing conditions of employment to motivate effective teaching; investing in curriculum development that recognises relationships between learning and costs; mapping provision to control costs related to school size and location; promoting formative assessment embedded in learning; reforming high-stakes examinations to reduce repetition and encourage curricula implementation; and building decision-oriented information systems that include cost data.

- Increase levels of public educational investment to escape the financing traps. Most financing will be supported by domestic revenue. Measures are needed to increase government income through fiscal reforms, more efficient and effective revenue collection, and greater budget shares for education. Grant aid, loans and other forms of concessional finance can catalyse change but are not sustainable solutions to inadequate funding and financing traps. More borrowing is not the answer in LICs and LMICs that are already highly indebted. If grants and loans are a significant part of the financing, they should respect the sentiments of the Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness. Shortfalls in finance have to be addressed with revenue streams that are recurrent and proportionate to levels of ambition. Consideration is needed of how to accelerate the development of fiscal states able to support essential public services, including education, largely from domestic revenue and prudent borrowing. Public financing is essential if access is not to be rationed by price and user fees.

- Identify and consolidate the evidence on the costs and benefits of different aid modalities. If external assistance is to be effective in helping to address financing traps in ways that are sustainable, then the evidence base on impact needs strengthening. The comparative advantages of grant aid, concessional lending, philanthropic support, project-based approaches, general budget support, blended financing and other approaches need critical appraisal. Circumstances have changed with new agencies, sovereign wealth funds, changing appetites for aid to education, and competition for funding from other sectors. Different agencies have shifting criteria of eligibility for aid. Some forms of aid may change incentives to generate domestic revenue. Performance-based contracting has both positive and negative effects. Resources are under pressure, making it more important than ever to understand the comparative advantages of different kinds of external assistance and promote approaches that can catalyse sustainable progress.