In two weeks’ time, G20 governments will inch their way towards acting on the climate crisis at the next Summit in Rome. But announcing far away targets and boasting about new renewables capacity won’t cut it. They know that the only way to avoid dangerous climate change is to fast-track the end of fossil fuels. To do so, they must shift all public finance flows, from government subsidies to international finance, away from high-carbon activities – and they must direct them towards initiatives supporting clean energy, resilience and adaptation.

In this year’s Climate Transparency report, launched today, we track the progress they have made towards doing so. Below we outline five key areas of finance that can help make or break decisive and timely action to avoid the most dangerous consequences of climate change.

1. Central banks and regulators finally showing leadership

Central banks and financial regulators play a critical role in shifting financial flows away from carbon-intensive activities. Many of them now clearly understand the impact of climate risks on financial stability and price volatility. However, while there are some outliers like the Central Bank of France and Bank of China which have pledged to stop financing coal projects , most banks have so far only committed to more transparent financial disclosures.

This is not enough. The urgency of climate risks requires central banks and regulatory agencies to act more boldly. Although there are initiatives in place for climate-related financial disclosures, these disclosures are not effectively incorporated in decision-making. A strong model for assessing disclosures by central finance institutions can inform investments and prevent climate shocks.

Other steps that can bolster efforts include mapping severe economic scenarios of climate impacts through ‘stress testing’. These stress tests can help central banks to identify systemic vulnerability to their investment portfolio from both physical risks (such as droughts and floods) and transitions risks (for example, fossil fuel assets getting ‘stranded’ and becoming uneconomical), and put in place associated risk mitigation measures.

Central banks have significant influence over our economies. If they chose to, they could be role-models, influencing and encouraging private financial institutions’ and commercial banks’ transition to climate finance.

2. Establishing carbon pricing schemes – with robust prices and coverage

Imposing a price on carbon is one way to create both negative and positive incentives. Carbon pricing can discourage emitters while boosting low-carbon alternatives and higher energy efficiency across different sectors of the economy.

In their July 2021 communiqué, G20 Finance Ministers reiterated the need for countries to collaborate more closely on carbon pricing. An example of this is the recent EU proposal for a new Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism. The framework aims to prevent the practice commonly known as ‘carbon leakage’: moving carbon-intensive production abroad to avoid paying the price of carbon domestically.

We have seen progress on this front on national levels, including in the G20. Five years ago, only 10 G20 member governments had some form of carbon pricing scheme, whereas in 2020 the number had risen to 13. Also, earlier this year, China launched its long-awaited national carbon Emissions Trading Scheme for the power sector, and carbon prices at EU level have encouragingly risen during 2021, reaching record-high levels above EUR 60/tCO2e.

However, as it is often the case, the devil is in the details. For carbon pricing to be an effective tool for emissions reduction, both the price of carbon and the extent of emissions covered need to be high enough to create the right economic incentives. In 2020, only France among the G20 had a national carbon price that exceeded the USD 40/tCO2e threshold recommended by the High-Level Commission on Carbon Prices. Emissions coverage greatly varies but tends to be generally low. More countries need to promptly implement some form of carbon pricing and make sure that most of their emissions across sectors are covered by it at sufficiently high prices.

3. Phasing out subsidies for fossil fuel production and consumption

The 2020 Production Gap report found that to keep global heating to 1.5°C, fossil fuel production must decrease by roughly 6% per year until 2030. But G20 governments continue to provide high levels of subsidies to fossil fuels which is creating perverse incentives for their extraction and use. This is critically hindering the low-carbon transition in taking place.

Just in 2019, G20 members, excluding Saudi Arabia, provided at least USD 152bn in subsidies for the production and consumption of coal, oil, and gas, with almost 40% of these subsidies being directed at oil. While the past five years have seen a reduction in fossil fuel subsidies as a proportion of GDP in some of the G20 countries, subsidies have increased in others. Ultimately, no country has announced a plan to phase them out in line with climate targets.

It’s of course important to recognise that some subsidies (such as those lowering the price of fuel electricity) are politically contentious and very hard to remove. However, the time has come to untangle our economies from this carbon dependency.

G20 governments need to bite the bullet and put in place robust programmes of reform which repurpose the earlier subsidy spends for social goods such as healthcare and education. They must also adequately compensate vulnerable consumers who are impacted by subsidy reform through well-targeted support measures. This will allow them to live up to their 2009 commitment to phase out ‘inefficient’ subsidies over the ‘medium term’ and contribute to re-aligning the use of public finance to the goals of the Paris Agreement.

4. No longer financing fossil fuel activities abroad

For so long, governments have only been held to account on climate action at home, and not on the activities they finance abroad. However, the realisation that countries must align all finance flows – public and private, domestic and abroad – with a climate-compatible world is finally emerging. Over the past year, we have seen major strides in moving away from public financing for fossil fuels.

In May this year, G7 nations committed to ending the use of public finance for new, unabated international coal power plants. South Korea also made a similar commitment. In addition, the US Treasury has announced a significant step away from international coal and gas projects through development finance. Last month, China also committed to end coal financing abroad. However, to support the phase-out of these fuels in line with climate goals, such restrictions must be rapidly expanded to include oil and gas.

The UK, who will host this year’s United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP26) in two weeks’ time, made a bold commitment to end all fossil fuel finance internationally (even though it is unclear on natural gas projects). This follows similar commitments by EU’s public finance institutions such as the European Investment Bank (EIB) and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD). But such commitments must become watertight – with loopholes around natural gas closed – and they must become the international standard for other major financiers.

5. Supporting developing countries with climate finance needs

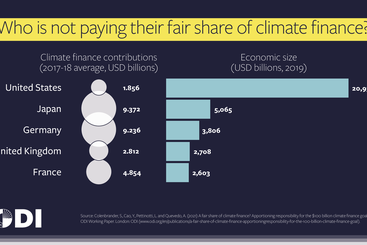

Under the Paris Agreement, nine G20 members (the G7 countries, Australia and the EU) are required to provide public and private financing to support the climate needs of developing countries. This financing is crucial to support countries put in place stronger mitigation efforts and build resilience against the impacts of climate change. But many estimates suggest they are still falling short of the target. New ODI research shows which countries are not providing their ‘fair’ share of climate finance based on the size of their economies, emissions and populations.

COP26 will kick-start negotiations towards a new climate finance goal, which will need to exceed the existing target of mobilising USD 100bn a year from 2020. At their Summit this year, G7 countries reaffirmed their existing commitment through to 2025. And, last month, the European Commission committed an additional EUR 4bn (USD 5bn) by 2027 to support low-income and climate-vulnerable countries.

With climate finance needs estimated to be far beyond USD 100bn a year, donor countries will need to show clear commitments to greater climate finance ambition than the current targets. Moreover, they must use robust transparency and accountability mechanisms to ensure resources are effectively spent on quality projects. In this respect, the G7 commitment to end overseas development aid for new coal is a key step in ensuring all finance flows are aligned with the Paris Agreement goal.