Today, development experts from a range of organisations and universities, including the World Bank, are gathering at ODI to discuss how we can end extreme poverty.

'Pro-poor' or 'inclusive' growth - ensuring that growth benefits the poor more than the average - is a popular mechanism for achieving this. For example, the Sustainable Development Goals and the World Bank both have targets that aim to promote income growth for the bottom 40% of every country’s population.

While we should welcome this recognition that who benefits from growth matters just as much as the amount of growth, some myths around this remain.

Myth 1: in poor countries, GDP growth translates into improvements in household living standards.

This myth is based on the idea that if developing countries focus on lifting GDP growth, this will raise average household living standards.

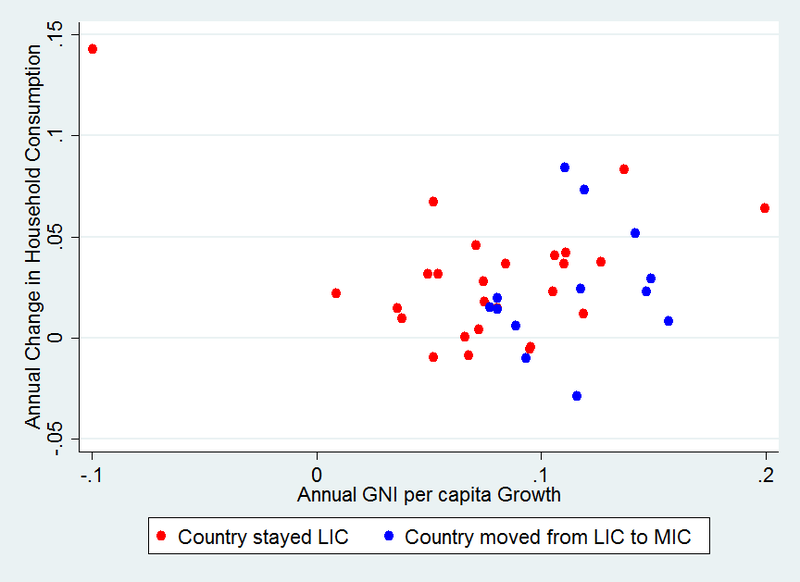

But forthcoming ODI research illustrates that for the poorest countries, there is not a clear relationship between GDP growth and average household levels of consumption. This can been seen in the chart below of countries that had low income status around 2000.

It's not clear whether this is due to a disconnect between the formal economy and household living standards, or problems with how we measure these.

Myth 2: countries that gained middle-income status over the last decade have higher levels of inequality.

This common belief is based on the Kuznets Curve, which suggested that as countries move from low to medium standards of living, inequality worsens. Recent UN publications reinforce this idea by providing evidence for it on average.

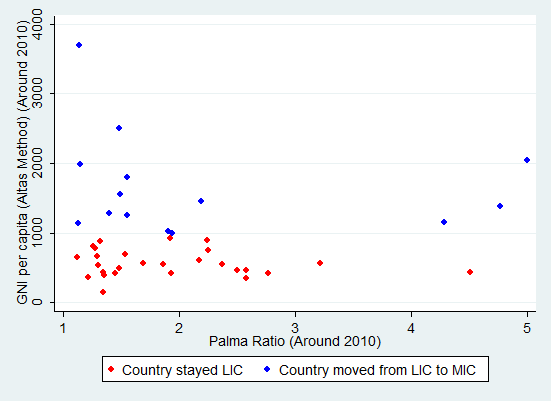

However, forthcoming ODI research illustrates that this average is driven entirely by a few outliers, as seen in the chart below of countries that had low-income status around 2000.

In fact, if you exclude the four outlier countries on the far right of the chart (Honduras, Zambia, Lesotho and Central African Republic) then the opposite is true. Countries that moved from low to middle income status are slightly more equal on average than those that stayed low income.

Myth 3: growth benefits the poor just as much as everyone else.

This myth was spread by a misinterpretation of a famous World Bank paper by Dollar and Kraay, Growth is Good for the Poor, which shows that on average the bottom end of the distribution has grown roughly as fast as the mean. This led some to argue that the poor always benefited from growth as much as everyone else in all countries.

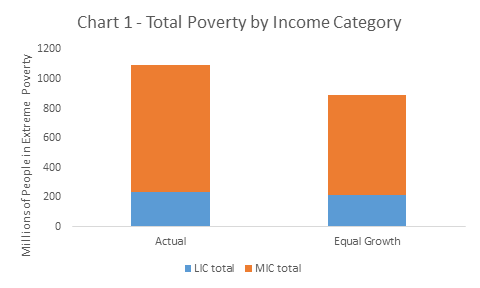

But an ODI paper shows that while around half of countries experienced ‘pro-poor’ growth, 80% of the world population lived in countries where the income of the bottom 40% grew slower than the average.

If all countries had experienced equal growth over the last three decades, 200 million more people would have escaped extreme poverty by 2010. As this chart shows, these 200 million people are in middle-income countries.

Myth 4: pro-poor growth will reduce the income gap between rich and poor.

A common misunderstanding is that if growth was higher for the poorer parts of the distribution, this would reduce the income gap between rich and poor.

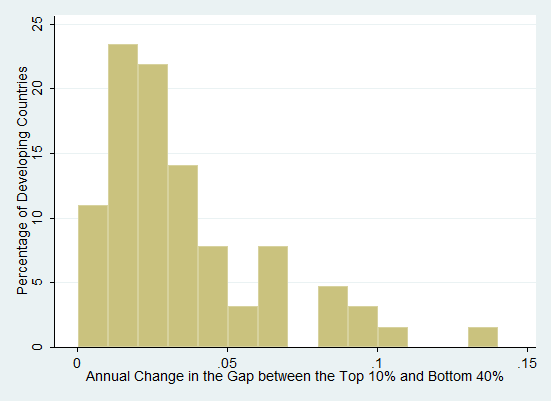

In fact, as a new ODI paper illustrates, the gap in incomes between rich and poor has increased in all countries that experienced positive growth over the last three decades.

This chart shows how the gap between the average income of the top 10% and bottom 40% grew each year.

Myth 5: we should focus on ending extreme poverty before addressing climate change.

Some commentators suggest that developing countries should focus on boosting growth to eliminate extreme poverty by 2030, and only then worry about reducing carbon emissions. This implies that it's possible to delay addressing climate change and that its devastating effects will not push people back into extreme poverty.

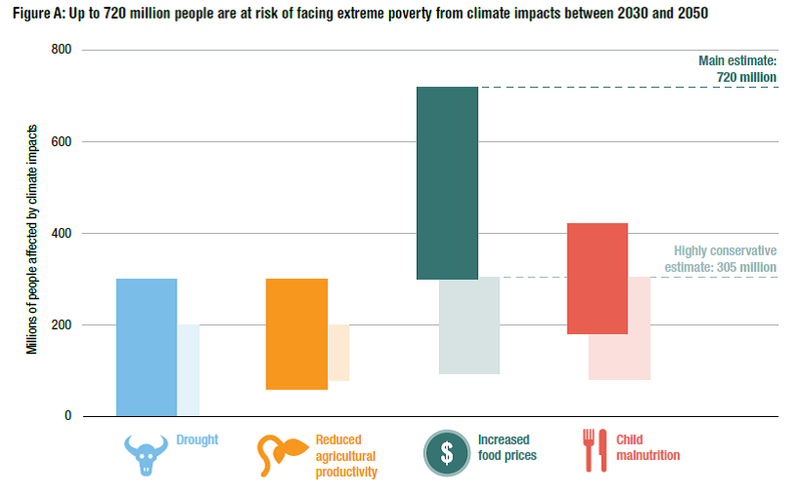

But an ODI report highlights that if action is not taken to address climate change immediately, over 700 million people could re-enter extreme poverty from 2030 to 2050.

So where does this leave us?

As our research shows, pro-poor growth can help eliminate extreme poverty. But this approach alone won't close the gap between the rich and the poor - and we can't try and address it without addressing climate change simultaneously.