Over the years, there’s been much discussion and attempts to get organisations and programmes to talk about ‘failures’ – things that are not working or situations where we made wrong calls.

You wouldn’t think this is so difficult given we all know that in international development, like in any other sector (or, generally in life!) things don’t necessarily work as we expect or assume. This is hardly a secret to anyone. But given the incentives in the sector to try to secure the next round of funding, we still tend to focus solely or mainly on what worked and where we succeeded.

Of course, there are some excellent examples and organisations that are ahead of the game. For instance, after publishing some Failure Reports, Engineers Without Borders Canada launched the Admitting Failure website where aid organisations can post their failed ventures. They felt this was needed as ‘fear, embarrassment, and intolerance of failure drives our learning underground and hinders innovation’.

There’s also been several Fail Festivals around the globe. Their aim is getting rid of the stigma of the ‘F-word’ and see it as a force for change.

But how to encourage learning from failures on a smaller scale? How to do it in a programme or consortia with multiple partners?

As a solution, we often talk about creating safe spaces for honest reflection and incentivising learning. But it can be difficult to come up with concrete actions to encourage sharing on what hasn’t worked between teams or partners who often are – let’s be honest – competitors outside of a particular project.

Fail Fest

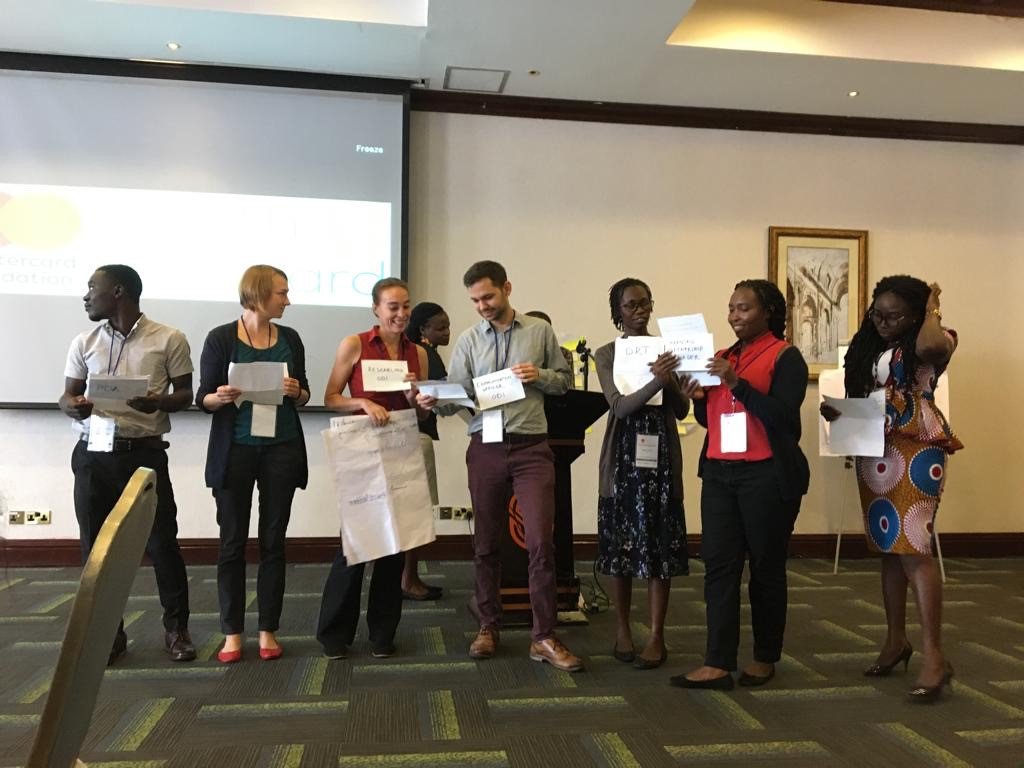

Smaller scale ‘Fail Fests’ have been popping up in recent years and we also trialled it at an annual learning event of the Youth Forward project. While we had talked about our challenges and things that haven’t worked well in previous events, this was the first time we did this explicitly. The feedback after the session? People really enjoyed it and 100% of participants rated it as useful.

When talking about Fail Fest with our colleagues in other programmes, we got a sense of growing interest to try something similar. To share our experience, we highlight four key learnings for when putting together a Fail Fest:

1. Redefine failure as an opportunity for learning

Our session was framed as ‘failing forward’ – the aim was to share where we failed but most importantly, what we had learned from the failure and what we would do differently next time.

2. Be mindful of power structures

If there’s any power hierarchy in the room, it’s recommended that a person or organisation at the ‘highest’ position starts by sharing their failure. This sets the tone and makes it easier and safer for others to follow. In our case, it was the funding partner who shared their failure example and what lessons they gained from it to ensure it wouldn’t happen again.

3. Tell a story

We are all drawn to stories and Fail Fest is not an exception. In our case, the most engaging stories were the ones where teams had prepared a short play or sketch: young people played angry parents, or in another story, a staff member took off some (not all!) of his clothes to make a point about getting rid of assumptions. Most of the stories were not only insightful but also funny – there’s something liberating about laughing together on things that have not worked.

This also made them memorable – which helped to get the point across on the importance of speaking up on failures and learning from mistakes. Indeed, feedback from participants revealed this was one of the top cross-cutting take-away lessons from the whole meeting.

4. Make it an interactive competition

To engage the audience, we made the Fail Fest an interactive competition with online, real-time voting and prizes for the best Failure Story. This lifted some of the seriousness and potential awkwardness of the session.

What about what didn’t work? Some of the ‘failures’ were not really failures as such – they were (often external) challenges that programmes had encountered and how they responded to them. And fair enough, those were real challenges, but on the other hand, obstacles are easier to share and discuss than failures. While the line between them can be blurry, it is important to try to go beyond challenges and identify situations where we could have acted differently – as those are the moments we tend to remember better and learn more about.

There are undoubtedly many potential ways to create safe spaces for learning within a programme or project. But given how difficult sharing what doesn’t work, especially across organisations, seems to be, we clearly need to come up with new ways to support and facilitate this.

Fail Fest is just one of the possibilities, but if done properly, it can strike a balance between story-telling, entertainment and candid reflection – something that comes across as a winning combo for learning.