Since 2015, British people have become more positive towards immigration, but their views are more complex than you might think.

This recent finding from Ipsos MORI seems to contradict the current prolific and polarising debate around this question. You must be either for immigration, enthusiastic about the positive economic and cultural effects of enhanced movement and integration, or against, fearful of the impact of the ‘other’ on your way of life and convinced that any new entrants would unfairly get valuable and scarce resources.

In fact, half of the UK population is not for or against migration, but lie somewhere in the middle. They feel a moral duty to help refugees, and they recognise the value that migrants bring to a range of sectors such as the NHS. But they are also worried about the impact of increased immigration on Britain’s culture, security and economic stability. The opportunities to engage on migration issues lies here, in the murky ‘anxious middle’.

What does the world think?

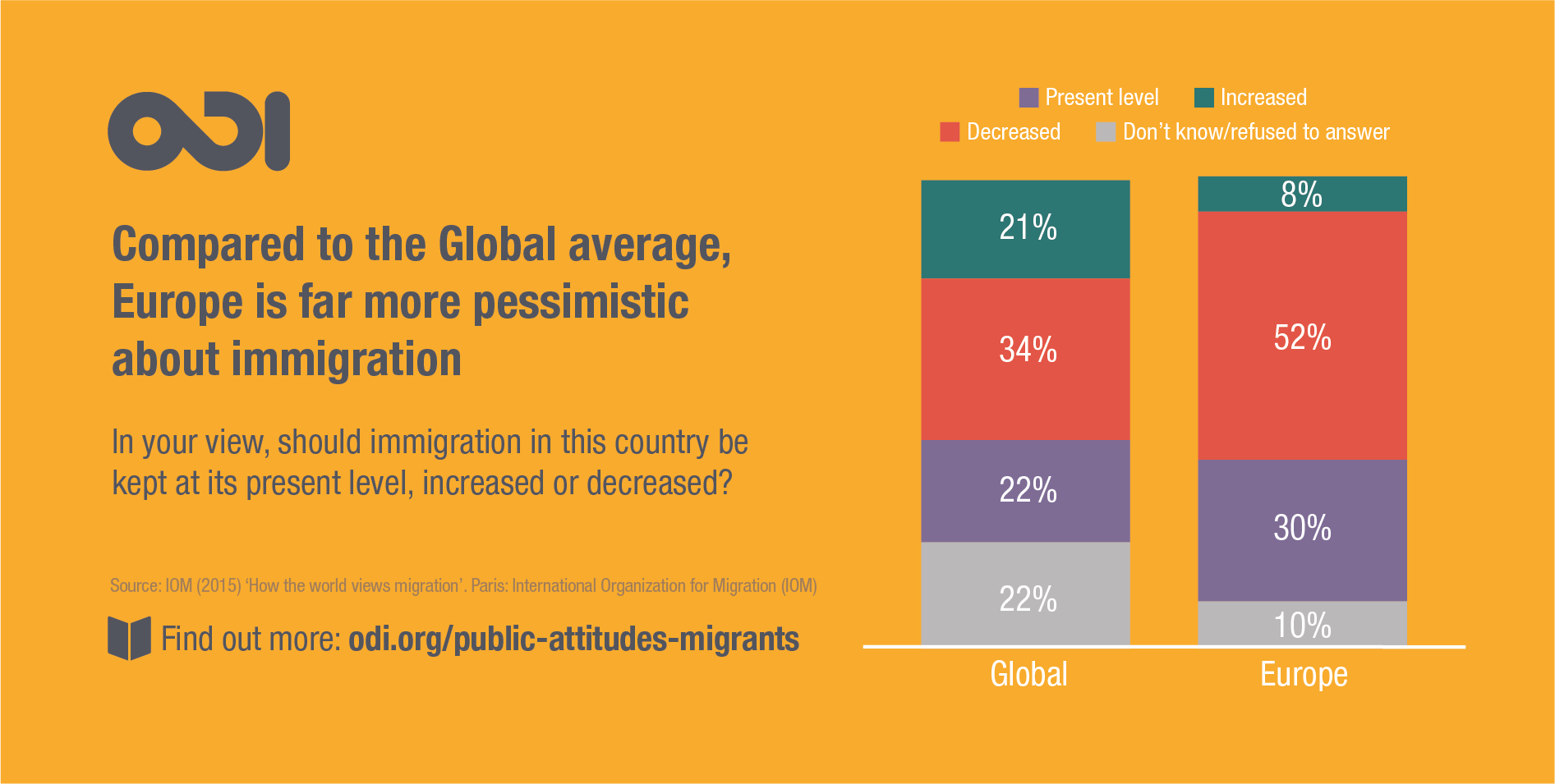

Recently, we looked at what people around the world thought about refugees and migrants. Half of all people think there are too many immigrants in their country. Most support refugees, but a third still feel borders should be closed. Compared to the global average, Europe is far more pessimistic. Even within Europe, there is huge variation between, and within, countries. For example, in the UK, those in Greater London are twice as positive as those in industrial and manufacturing towns.

What people think is determined by who they are, and who they are thinking of when asked the question. On the latter, people are more negative towards generic ‘immigration’ than they are towards specific groups. Illegal immigration is far more worrying than legal immigration. And in Europe, people prefer migrants who will economically contribute: those who are highly-skilled such as doctors and teachers, and those with qualifications.

And on the former, younger, more liberal, and more educated people are generally more welcoming. Interestingly, there is a generational rather than an age effect – people have different formative influences and retain their views as they get older.

Yet demographics aren’t the main predictor. There have been recent moves towards ‘attitudinal segmentation’ – grouping people based on what they think, rather than their characteristics. For example, Fear and HOPE have segmented the UK public into six distinct ‘tribes’: ‘confident multiculturals’, ‘mainstream liberals’. ‘immigrant ambivalence’, ‘culturally concerned’, ‘latent hostiles’ and ‘active enmity’.

How can you engage with public attitudes?

So what does all this mean for advocacy efforts? Two days after Ipsos’s report launch, I spoke with Save the Children’s European migration advocacy advisers. Given the difficulties of targeting increasingly anti-immigrant political parties, they were instead turning to the public. We discussed the following three strategies:

1. Go local

Messaging about the national level economic benefits of immigration is unlikely to resonate with those who are acutely feeling the local impact of low wages and a lack of social services. Policy-makers and advocacy groups need to understand local views, perhaps through attitudinal segmentation, and tailor messages and policies accordingly.

2. Work with the media

How migration is covered in the media tends to determine the shape and content of public debate. Some outlets are overwhelmingly negative, ignoring the positive contributions many migrants make to their host communities. Others are overwhelmingly positive, ignoring the negative impacts immigration can have. So how can civil society engage? One way is by pairing those with access to migrant stories with the journalists who wish to produce more balanced portrayals.

3. Avoid 'myth-busting’

Merely providing facts is unlikely to allay concerns, for two reasons. Firstly, because of the bias against ‘experts’. For example, when asked how many immigrants are in their country, people frequently estimate double the actual number. When told the actual number, they tend to distrust the official statistics. Secondly, as outlined above, such national level statistics are unlikely to speak to the real concerns people feel on the local level.

This does not mean facts and evidence are not important. Indeed, they are especially necessary when engaging with policy-makers. However, they are unlikely to be a persuasive tool on their own. Instead, advocates should explore innovative ways to explain journeys and experiences, such as the fact that most of us were migrants at some point.

Of course, the discussion above bypasses other important questions, like how to engage with anti-immigrant political parties, or news outlets which peddle ‘fake news’. It’s also subjective, and context specific. Hopefully though it can help identify what works and what doesn’t in engaging with the migration public debate.