Low- and middle-income countries (L&MICs) face unparalleled challenges to their future growth and development. Covid-19 and climate change have combined to reverse years of development progress and have created extraordinary challenges, made much worse by the impact of the war in Ukraine. As the Spring Meetings of the World Bank and IMF get under way this week, focused on supporting a sustainable and resilient recovery, it is timely to reflect on the response of development finance institutions (DFIs) to the pandemic and how they are positioned to support it. We have had a first look at the data reported in DFI reports published so far and note four takeaways.

1. DFIs rolled up their sleeves and increased their investment

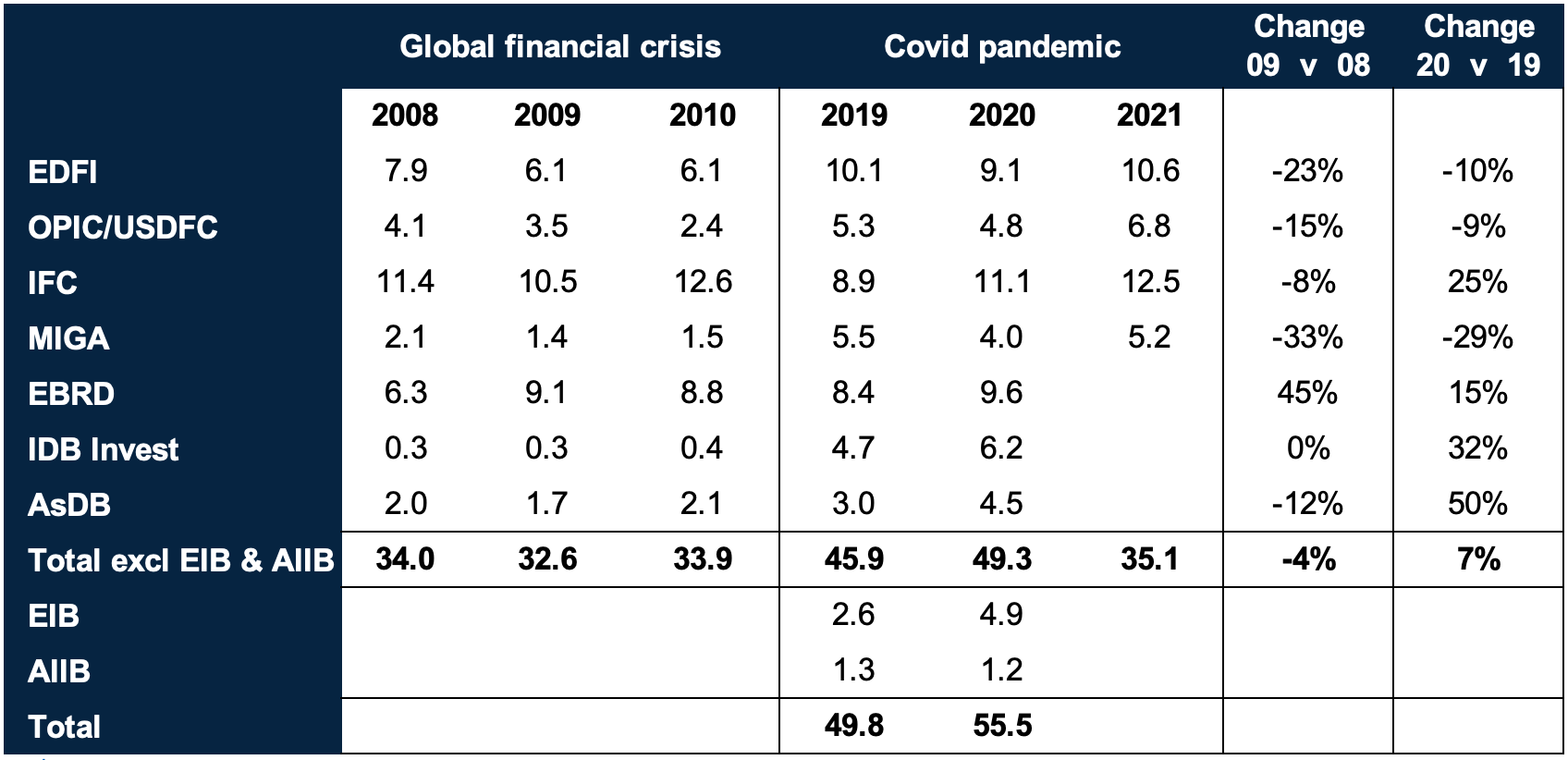

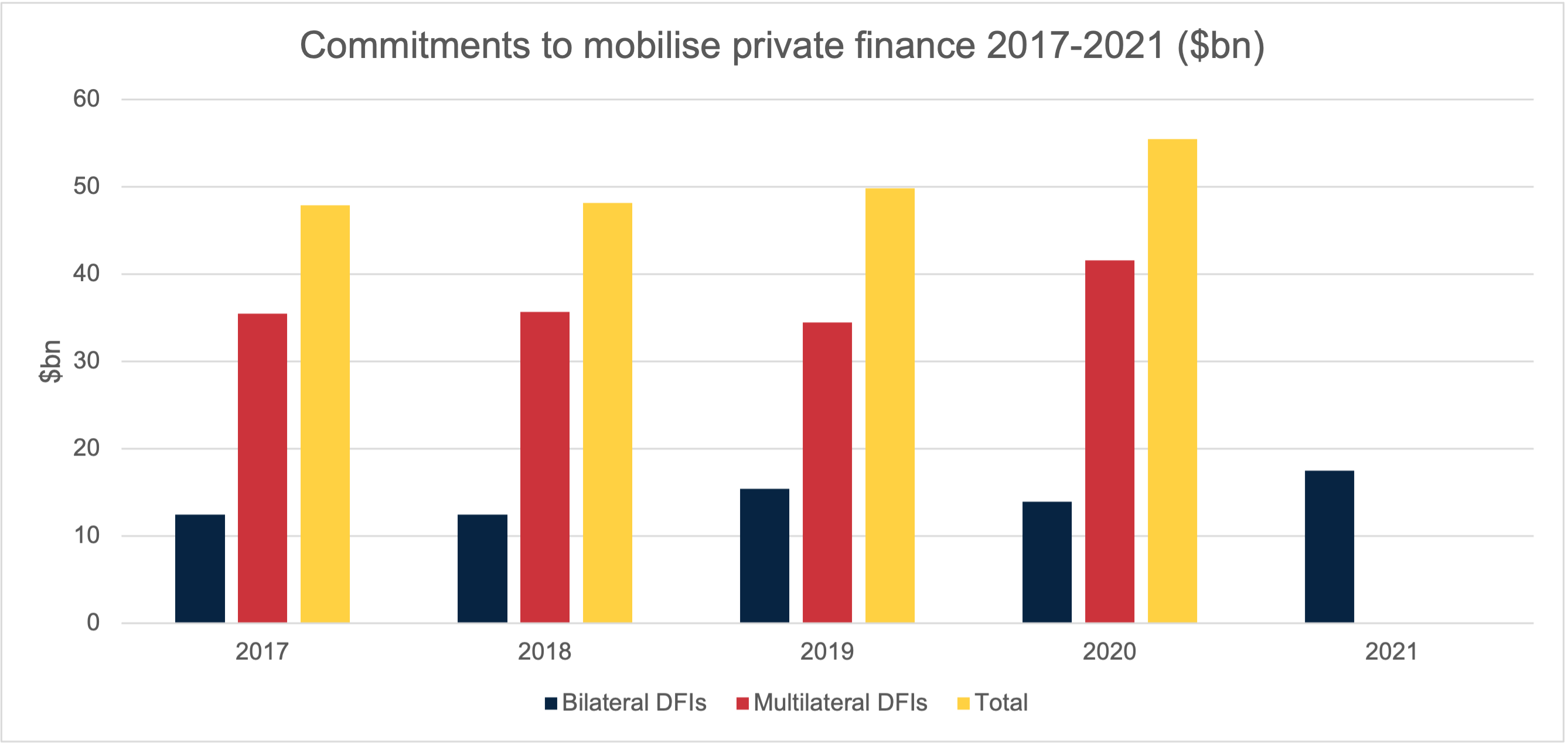

Compared to the global financial crisis, where the collective volume of DFI investment fell by 4%, it held up relatively well in the first year of the Covid-19 pandemic. DFIs collectively increased their investment by 7% in 2020 to help cushion the economic impact of Covid-19 (Table 1). This increase was driven by multilateral DFIs who increased their investment by 21% in the first year of the pandemic. While bilateral DFI investment tailed off in 2020 it bounced back in 2021, re-establishing a trend of relatively fast annualised growth in investment of 7% over the period 2017-2021.

This rise was mainly driven by a 28% increase in US International Development Finance Corporation (USDFC) in 2021 (enabled by the significant increase in firepower of the new USDFC created in December 2019). This compares to a smaller annualised growth rate in investment of 1.1% of the International Finance Corporation (IFC) and Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA) over the same period (data for other multilateral DFIs is not yet available for 2021). Assuming other multilateral DFI investment in 2021 doesn’t fall from 2020, total DFI investment would reach $61.6 billion in 2021, an increase of 24% from pre-pandemic levels.

Table 1: DFI response to global financial crisis and Covid-19 pandemic compared

Figure 1: annual investment commitment by type of institution ($ billion), 2017-2021

2. DFIs responded in an agile and flexible way with emphasis on liquidity support rather than new greenfield investment, further increasing the concentration of DFI investment in the financial sector

To respond quickly, DFIs had to become more flexible in the kinds of support and investment they made, sometimes taking on a higher share of risk than usual and offering new products such as working capital loans for the first time. Given lockdowns and restrictions on travel, DFIs adopted new ways of working such as remote due diligence and stepped-up collaboration with other DFIs. To get cash out the door quickly they simplified their approval, commitment and disbursement processes.

We haven’t yet been able to crunch the detailed data to understand the makeup of these total volumes (e.g. by sector, geography and instrument), but we have some clues about how the nature of DFI investment has changed due to the specific nature of the Covid-19 crisis.

There is no doubt that the world was a difficult place to invest and do business in 2020 as the global economy ground to a halt with the implementation of lockdowns worldwide, but with stakeholders calling for a counter-cyclical response, DFIs were under pressure to ramp up their investment. However, originating new deals in this context would perhaps have been a tall order and a lot of investment would have been put on hold as 75% of the world’s L&MICs entered recession.

This challenging investment environment, for example, can be seen by the collapse of infrastructure investment. The value of infrastructure investment which included private investment in L&MICs fell from $96.7 billion in 2019 to $45.7 billion in 2020, a staggering decline of 53%. Within this, Development and Export Finance Institution (DEFI) investment fell by 40% compared to a 41% fall in private investment and a 19% fall in public investment.

The unprecedented demand and supply shocks created by governments’ responses to Covid-19 meant that businesses in L&MICs were mainly concerned with staying afloat. For DFIs in 2020, it meant originating new deals and supporting expansion of their clients were not the ‘name of the game'. There were exceptions if opportunities arose for DFIs to support existing clients to retool or reorientate their operations or make new investment to support country efforts to fight the global pandemic. This includes investment to increase personal protective equipment and vaccine manufacturing capacity in L&MICs.

Consequently, DFIs focused on supporting the viability of their investees and protecting jobs through the provision of emergency working capital support, repayment holidays and technical advice to their existing businesses. They also helped to keep trade flowing through expanded trade financing facilities, and helped strengthen country financial systems by pumping liquidity into domestic financial institutions to ease local credit tightening.

Some examples of large fast track liquidity and trade finance facilities launched during the early stage of the crisis included an IFC $8 billion facility and a $6.5 billion MIGA facility in April 2020, a USDFC $4 billion facility in May 2020 and an Asian Development Bank (ADB) revolving trade finance facility which committed $2.4 billion in 2020. However, anecdotal evidence suggests that the degree of demand for such liquidity support was not as high as some DFIs had initially anticipated at the inception of the crisis, with DFI investee companies proving to be more resilient than expected.

This focus has resulted in a change in the sectoral allocation of DFI investment in 2020 with an increased % allocation to the financial sector in 2020 compared to 2019. For example, 50% of collective European DFI investment (EDFI) went to the finance sector in 2020 compared to 41% in 2019. We therefore see a continuing trend of an increasing concentration in the financial sector in DFIs portfolios. At the end of 2020, 31% of EDFI’s collective portfolio and 48% of the IFC’s portfolio was invested in the financial sector.

3. The ‘asks’ of DFIs have got bigger, but the operating environment has got harder

DFIs face a dual challenge going forward. DFI shareholders and stakeholders have increased their expectations about what DFIs should do to support the economic recovery in L&MICs, but their operating environment has become more challenging.

The ‘asks’ have got bigger. Covid-19 has reversed years of development progress and dramatically increased development needs, widening the SDG financing gap. Given already stretched aid budgets, DFIs will be under increased pressure to materially scale the mobilisation of private finance, to help fill this larger financing gap. The numbers aren’t in yet but it is expected that they will have mobilised less in 2020 with difficult headwinds ahead. They will also come under more pressure to step up their investment to ignite growth in the poorest countries and help mitigate against the emerging divergent recovery, which threatens to leave these countries behind.

Furthermore, they will be expected to accelerate their ‘green’ investment to support a recovery which is low carbon, climate resilient, inclusive and just; as well as make investment to strengthen healthcare supply chains to build resilience to future pandemics. Delivering these asks will require changes to what, where and how DFIs invest.

These increased ‘asks’ come at a time when DFIs are facing a harder operating environment, making it more challenging for them to find investable deals and scale their investment Firstly, DFIs entered the crisis with a low annualised investment growth rate of 1.3% (2017 to 2019). For many DFIs, the increase in 2020 investment was driven by increases in short term liquidity facilities to the banking sector. These will most likely be paid back quickly and have been enabled by short term balance sheet juggling and dipping into reserves rather than new capital injections.

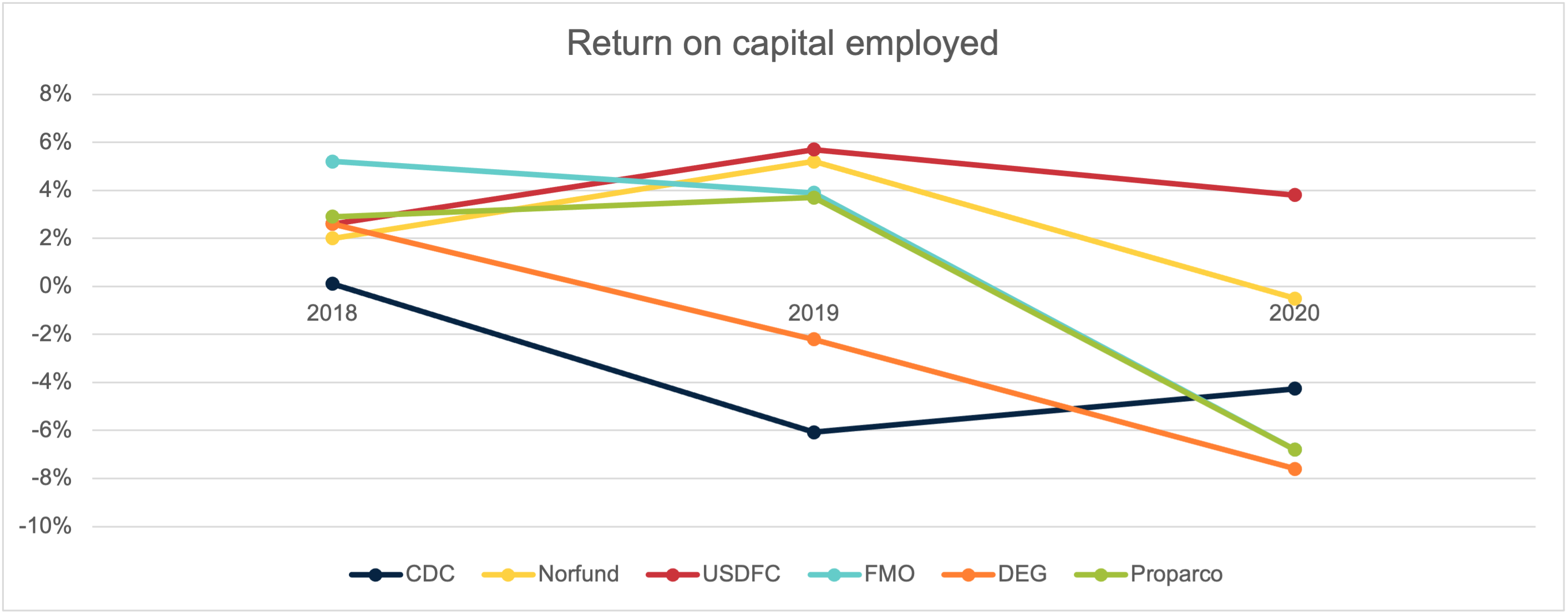

However, the pandemic has put a strain on the balance sheets and profitability of many DFIs due to unrealised losses in equity valuations, higher provisioning for losses and postponement of dividends and loan repayment holidays etc (Figure 2). Once these short-term facilities are unwound, it is difficult to see how DFIs can maintain the stepped-up investment levels seen and make increased high-risk investment in the poorest countries without new capital funding.

Secondly, continued economic weakness will make it harder and more costly for DFIs to source and develop investment opportunities and mobilise private investment. Some notable storm clouds on the horizon include the increased risks of sovereign debt distress in L&MICs, where 30 out of the 73 countries eligible for the debt suspension initiative are at high risk of external debt distress and tighter financing conditions as monetary policy tightens in the US and other advanced economies. These storm clouds will increase both the risk and cost of borrowing for investors investing in L&MICs and will act as a drag on new investment.

Figure 2: impact of Covid-19 pandemic on bilateral profitability (ODI forthcoming)

4. DFIs and their shareholders need to step outside their comfort zones

Our research has found that inherent tensions exist between these ‘asks’ and that DFIs face an ‘investment trilemma’ in delivering them. For example, mobilising huge sums from institutional investors may be at odds with securing higher development impact in poorer countries, which may also involve the acceptance of higher risk to financial return. This could threaten DFI profitability.

Similarly, to support the ‘green’ transition and secure higher development impact (as technologies such as solar and wind become cheaper and cost competitive), DFIs will need to the use more ‘venture like’ capital to support the development of new low carbon technologies and products. This will also involve the acceptance of higher risk to financial return and hence DFI profitability.

Given the deterioration in the operating environment, it is difficult to see how DFIs can deliver these ‘asks’, unless they step out of their comfort zones. This requires bold action by shareholders and DFIs. Shareholders will need a clearer understanding of the tensions that exist between these ‘asks’ and the implications for business models, profitability and funding of DFIs. The balance struck will vary by DFI. This understanding will help them set much clearer objectives which balance these ‘asks’ in different countries and sectors. Whatever the balance, it will likely require a greater acceptance of risk and a greater use of subsidy which will need to be funded.

Depending on DFI funding models, shareholders and donors will most likely need to put their hands in their pockets. But they should only do this if DFIs change what, where and how they invest – more investment in the real economy, more investment to support the development of investment opportunities, more high-risk investment, new products and approaches to attract institutional investors, more strategic, coordinated collaborative investment – to name a few of the changes required.

The now unprecedented nature of the development challenge demands this urgent change. Without it, we will not be able to shift the needle and when we look back in 2030, all the talk of supporting a sustainable, inclusive and just recovery will have been hot air.