From redundancy announcements at Meta, Amazon and Twitter to the collapse of FTX, Big Tech is in the doldrums. Governments will be pondering how to react to the bursting of the tech bubble, but there are opportunities to grasp too: after years of being outbid by the private sector for tech talent, can the public sector finally play catch-up?

In this instalment of Budgets and Bytes, we look at a recent World Bank report on GovTech and a linked blog post for suggestions as to how governments can become more attractive to digital workers.

The competition for tech talent

The public sector is in the midst of a digital transformation that aims to take advantage of new technologies and ways of working. The advantages of digitalisation range from improved efficiency and effectiveness of public services to leveraging insights from large datasets and AI – as illustrated during the Covid-19 crisis. While the vision of ‘Government as a Platform’ remains more of an aspiration than reality, digitalisation is now an important part of public sector reform.

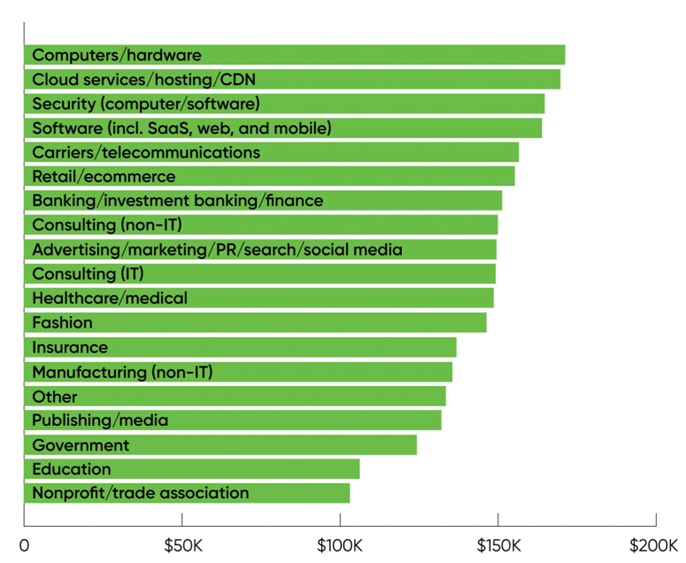

Part of this drive includes hiring people with the digital skills to deliver this agenda. However, governments have struggled to hire and retain the top tech talent who could support digitalisation efforts. An O’Reilly survey of data and AI professionals (mainly from the US) found that government salaries were around 25% lower than those offered in the tech sector (i.e. the top four sectors in Figure 1).

Figure 1: Average salary by industry

Government is also a laggard in terms of implementation. Another O’Reilly survey in 2022 found that government was the joint-lowest sector in terms of ‘maturity’ in its use of AI (defined as using AI in production), and was much more likely to be ‘considering’ or ‘evaluating’ AI rather than using it concretely.

Tech crisis: an opportunity for government?

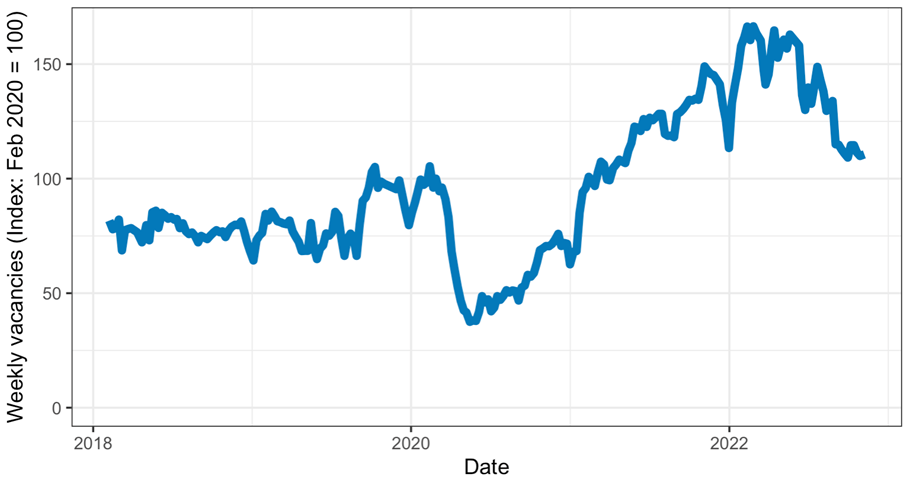

However, the era of skyrocketing demand for tech professionals may be coming to an end. Data for the UK shows a sharp drop in online job vacancies in the ‘IT/Computing/Software’ sector since early 2022, confirming the anecdotal evidence provided by big tech companies’ mass lay-offs.

Figure 2: Weekly online job vacancies for IT/Computing/Software, UK, February 2018 to November 2022

Softening demand for tech workers should drive down wages in the sector and level the playing field between the public and private sectors. Furthermore, with many employees in the US tech sector on temporary visas (meaning they may have to return to their home country if they cannot find a new job within 60 days), we may witness a particularly strong increase in the supply of tech talent in low- and middle-income countries previously suffering from a tech brain-drain.

What more can government do?

Will this be enough for government to close the gap with the private sector? The World Bank recently published its Tech Savvy report with recommendations on advancing GovTech reforms in public administrations. While this is not the sole focus of the report, which advocates for a ‘whole-of-government’ approach to digital transformation, we picked out a few of their recommendations for improving the attractiveness of the public sector to skilled digital workers:

- Introducing more flexibility and agility in its working practices, moving away from ‘antiquated recruitment practices and bygone salary scales’;

- Highlighting public sector benefits such as a positive social impact, a good work-life balance and job security (something Twitter employees may have come to appreciate in the past few months) on the back of surveys that suggest highly-skilled digital workers are attracted by more than just compensation;

- Attracting graduates via specialised programmes to build a pipeline of talent from an early stage, such as the Australian Digital Cadetship Program or the UK’s Digital, Data, Technology and Cyber Fast Stream;

- Creating a digital culture that ‘embraces change, learning, and failure, and empowers workers to be creative’ to attract tech workers looking for ‘stimulating and innovative work’.

Challenges

The Tech Savvy report contains many helpful recommendations for governments to follow. However, there are several aspects of public sector work that are hard to change and will make it less attractive to tech talent.

First, the public sector frequently struggles to reward expertise (as economists and statisticians can testify), with more promotion opportunities for generalists with broader policy experience. Civil service promotions tend to go to policy officials, who work closer with ministers, while tech workers’ hard skills may take them further in private sector tech companies. This is a particular issue in public financial management where digital skills are often undervalued.

Second, machine learning models are only as good as the data they are built on – and the private digital sector has made a huge amount available to its data scientists. This is a key reason why universities have also struggled to retain top AI scientists, who can find more avenues for research using private sector data. The public sector does potentially have troves of administrative data, but it often struggles to make it exploitable – sometimes even for regular monitoring and evaluation, let alone for advanced data science analysis. For example, the UK Treasury’s IT system for financial management is unable to provide the required data for the Infrastructure and Projects Authority to track project costs and schedules to ensure they are on track, while most governments also fail to make budget data available to the wider public. The United Nations Statistics Division has created a Collaborative on the Use of Administrative Data for Statistics that seeks to support governments in addressing these issues.

Finally, government work often gets dominated by short-term ministerial priorities and ‘fire-fighting’ and there are few opportunities for innovative thinking or experimentation. This can often be identified as waste, which is prime for budget cuts. As a result, research is often outsourced to universities or consultancies. Meanwhile, there is a strong bias within public financial management towards the certainty that comes with outsourcing technology to big international software providers even if it results in locking government into less flexible solutions. Top tech talent may therefore find that they have fewer opportunities for innovation in the public sector. Furthermore, the delivery of core public services requires stability and reliability, making it ill-suited to the disruptive approaches sometimes favoured by digital start-ups (such as Facebook’s pre-2014 internal motto: ‘Move fast and break things’).

A whole-of-government approach

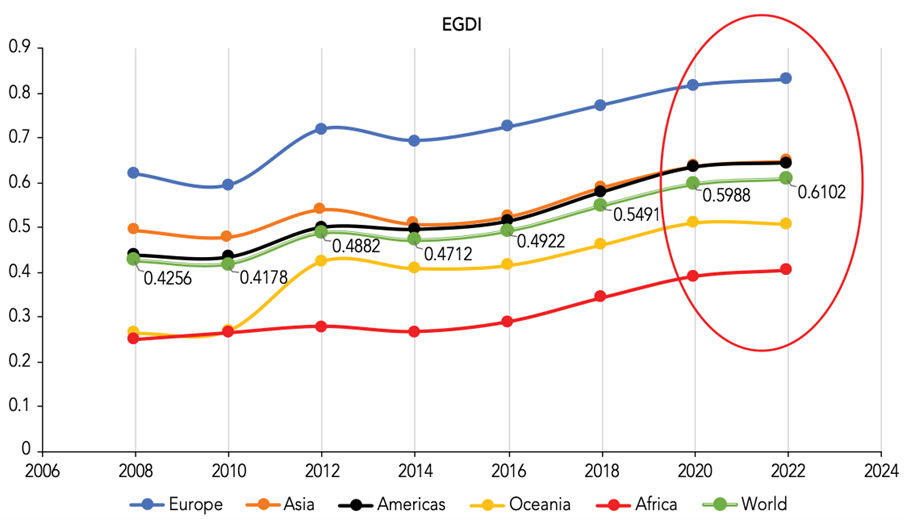

Despite these limitations, public sector digitalisation has steadily expanded over the past decade, as reflected in the progress of the UN’s E-Government Development Index (EGDI) across continents (with a notable plateau between 2020 and 2022). This, in turn, will create greater opportunities for digital workers, likely creating a positive dynamic as the public sector increasingly becomes a digital-friendly environment in which tech workers can see themselves building a career.

Figure 3: EGDI, average by region and worldwide, 2008-2022

The current tech downturn may help to level the playing field between the private and public sectors in terms of attracting tech workers. This presents a potential window of opportunity for governments to make significant strides in policy design, analysis and delivery, if they are willing to embrace digital ways of thinking and working, and invest in the talent to do so.