Earlier this year the Comoros Islands, a small archipelago off the coast of Mozambique, expressed interest in entering talks with the Kuwaiti government. The subject? A deal that would grant Comorian citizenship to the stateless Bidoon population of Kuwait and the United Arab Emirates (UAE), in return for aid.

The negotiations have been largely overlooked and even recently denied by the Kuwaiti government. We urgently need clarity about what’s happening: this initiative would both have drastic consequences for stateless people in the UAE and Kuwait, and set a dangerous precedent for vulnerable populations worldwide.

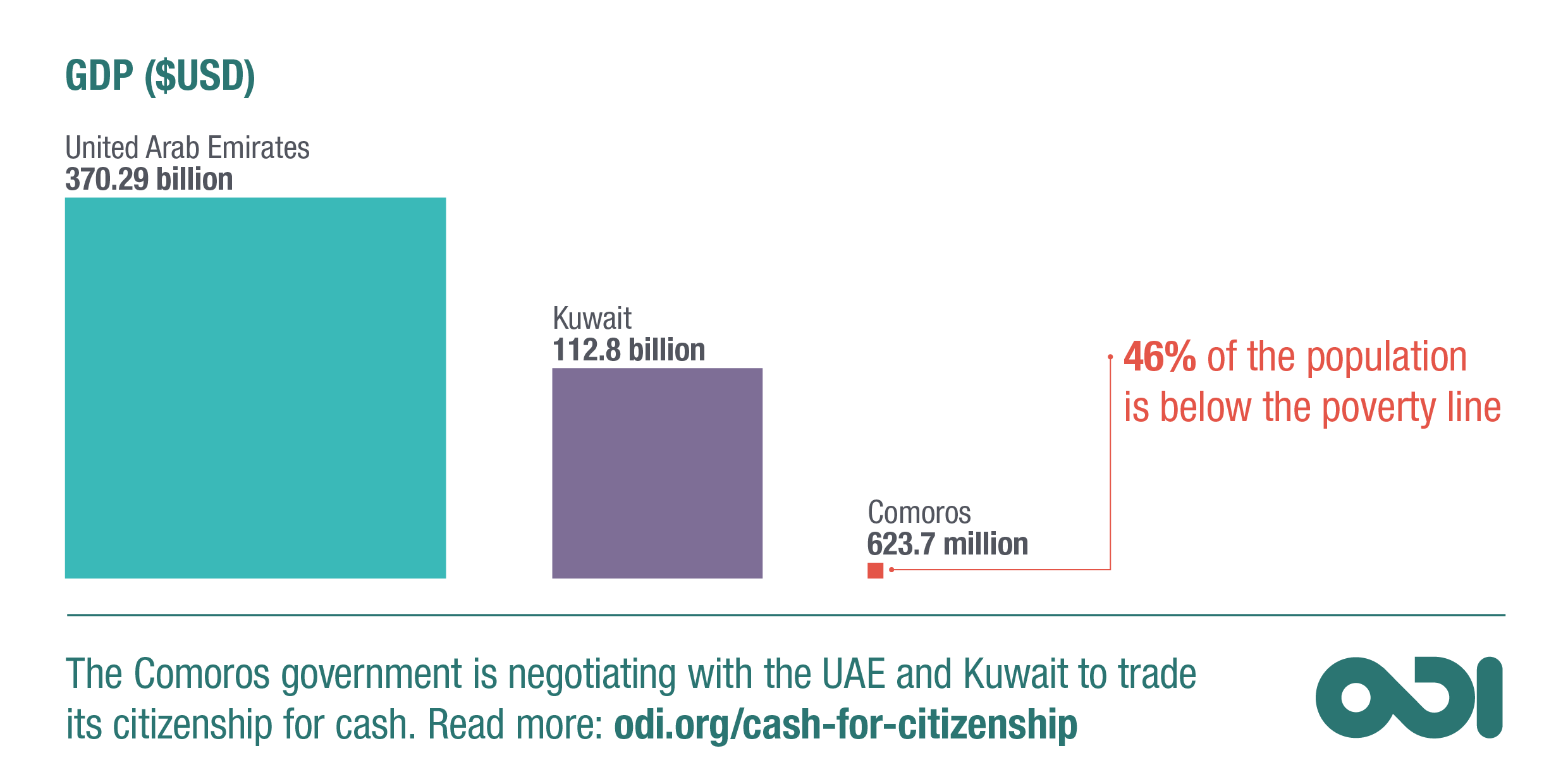

Almost half the Comorian population live in poverty

The Comoros has been struggling both politically and economically for decades.

Since gaining independence from France in 1975, it has experienced 20 coups or attempted coups. It is short on natural resources, heavily reliant on remittances (in Africa, it’s second only to Eritrea) and is reliant on the export of three crops which are vulnerable to price fluctuations and natural disasters. Today it is one of the poorest countries in the world; in 2004, 48% of its 800,000 inhabitants were living under the national poverty line.

Given these issues, Comorian politicians are seeking a quick, lucrative and easy solution. Since 2008, the Comoros government has been in negotiations with the UAE and Kuwait to trade its citizenship for cash.

Kuwait and the UAE have a record of marginalising the Arab Bidoon

Kuwait and the UAE, meanwhile, have been heavily criticised for denying hundreds of thousands of Bidoon their citizenship. Literally translated in Arabic as ‘the without’, Bidoon is a status that refers to those rendered ineligible for citizenship during the process of state formation over fifty years ago in the Arab Gulf states.

Many Bidoon failed to register at the time due to a lack of education and/or information. Some were unable to prove their residence in the country for a specified period of time. Others were denied for political reasons, often related to kinship, elitism and sectarianism. In Kuwait, for example, stripping citizens of citizenship was used as a political tool to silence dissent.

The Bidoon are primarily the descendants of nomadic Arab Bedouins, who roamed the Arabian desert for generations. Though most of the Bidoon today were born in the country in which they seek citizenship, and in some cases even served in the army, they continue to be excluded from the benefits of nationality.

Institutionalised discrimination is widely practiced. The Bidoon are barred from entering the labour market; denied education, health care, and freedom of movement; and undocumented Bidoons in particular live under the constant threat of arbitrary arrest and deportation.

Cash for citizenship

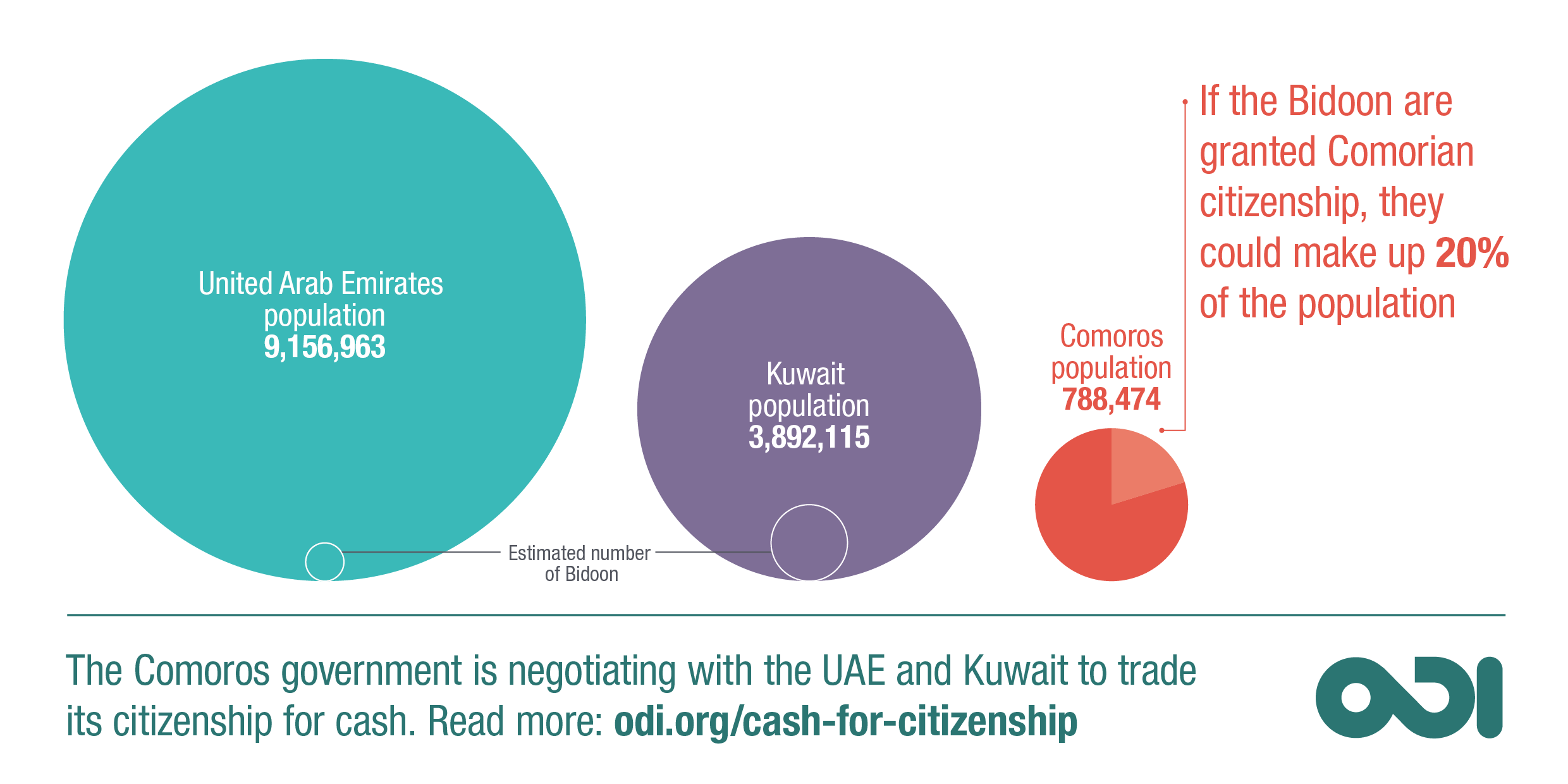

For Kuwait and the UAE, the answer is simple: buy citizenship rights for the Bidoon – in another country. The oil-rich Arab states are pledging aid to the Comoros Islands in exchange for the Bidoon being granted ‘Comorian economic citizenship’.

This threatens to uproot thousands of people from the only home they have known to a country they have no ties with, thousands of kilometres away, making them practically ‘migrant nationals’. Given the huge scale of the deal – reported to be worth $200 million with the UAE alone – there is the alarming possibility that the Bidoon will be forced into accepting this settlement.

So what outcome can we expect?

In 2012, Ahmed Abd al-Khaleq, a Bidoon advocate long harassed and imprisoned by the UAE government, was given a choice: indefinite detention, or exile to the Comoros Islands. After choosing the latter, he then reached a deal to be deported to Thailand, and was later resettled to Canada.

It is unclear whether Bidoon populations will similarly use the Comoros as a transition country until they resettle elsewhere, or what the impacts on (or reaction from) people in Comoros might be.

In theory, Arab aid could help rebuild the country economically, and the relocated Bidoon could be supported to integrate both socially and politically. But there is no way to tell whether this would succeed – and the risks do seem to outweigh the opportunities.

Implications for global migration

It is also not clear what the knock-on effects of the Comoros deal will be. Currently, many Bidoon are seeking asylum in Europe and elsewhere in the world. Will these countries reject the asylum claims, and require the Bidoon to take up their ‘right to a nationality’ offered by the Comoros? Given the current European views and measures in place to deter refugees and migrants, this is not a far-fetched assumption.

Perhaps more importantly, this deal could set a precedent for other countries seeking rid themselves of their unwanted populations. Today, there are at least 10 million stateless people worldwide. The UN and the international community have pledged their commitment to ending statelessness, yet this cannot happen unless states uphold their responsibilities towards ending this long-standing human rights violation.

Sources:

- http://www.unicef.org/infobycountry/comoros_statistics.html

- http://www.unicef.org/infobycountry/uae_statistics.html

- http://www.unicef.org/infobycountry/kuwait_statistics.html

- http://data.worldbank.org/country/comoros

- http://data.worldbank.org/country/united-arab-emirates

- http://data.worldbank.org/country/kuwait

- http://hdr.undp.org/sites/all/themes/hdr_theme/country-notes/KWT.pdf

- http://hdr.undp.org/sites/all/themes/hdr_theme/country-notes/ARE.pdf