Southeast Asian countries have seen a range of important meetings in this end of 2022, from the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation in Bangkok, Thailand, to the G20 summit gathered in Bali, Indonesia. On December 14th, the European Union (EU) and the Association of Southeast Asian nations (ASEAN) held a summit in Brussels, to commemorate the 45 years of their relationship. The EU-ASEAN relationship had been elevated them to a strategic partnership in 2020. In this blog, we argue that while the EU declares its interest in dealing with ASEAN, its economic relationship with the bloc is stagnant and concentrated in a few countries; and its infrastructural programme has not been responsive to the needs of the region. Making the EU-ASEAN partnership more inclusive and transformative will therefore require a step up in the EU’s offer to southeast Asia.

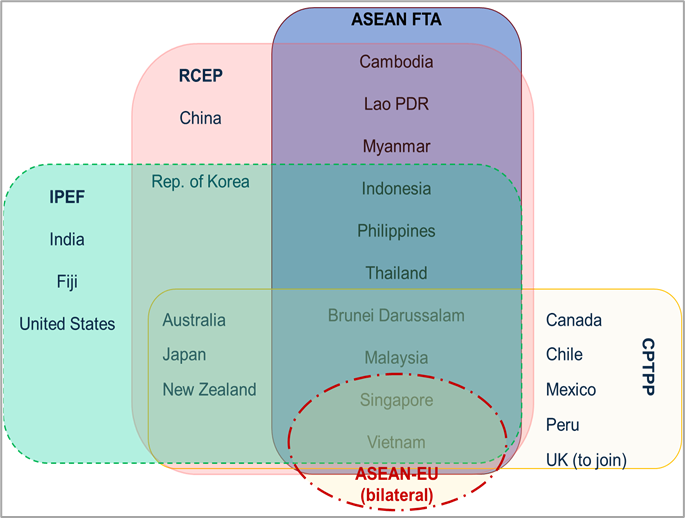

The EU is not the only player interested in strengthening its partnership with ASEAN countries, and with the broader Indo-pacific region. From Australia’s longstanding interests in the region to Obama’s ‘pivot to Asia’, to the UK’s ‘Indopacific tilt’, many countries are demonstrating renewed attention to the area stretching ‘from Bollywood to Hollywood’, of which ASEAN is the core (Figure 1). Much interest is likely to be a reaction to China’s increased presence in Asia. What does this mean, in practice, for Southeast Asian countries?

Figure 1. ASEAN countries are at the center of multilateral cooperation in the region

Dynamic and diversified trade will reinforce EU’s position as ASEAN’s economic and development partner

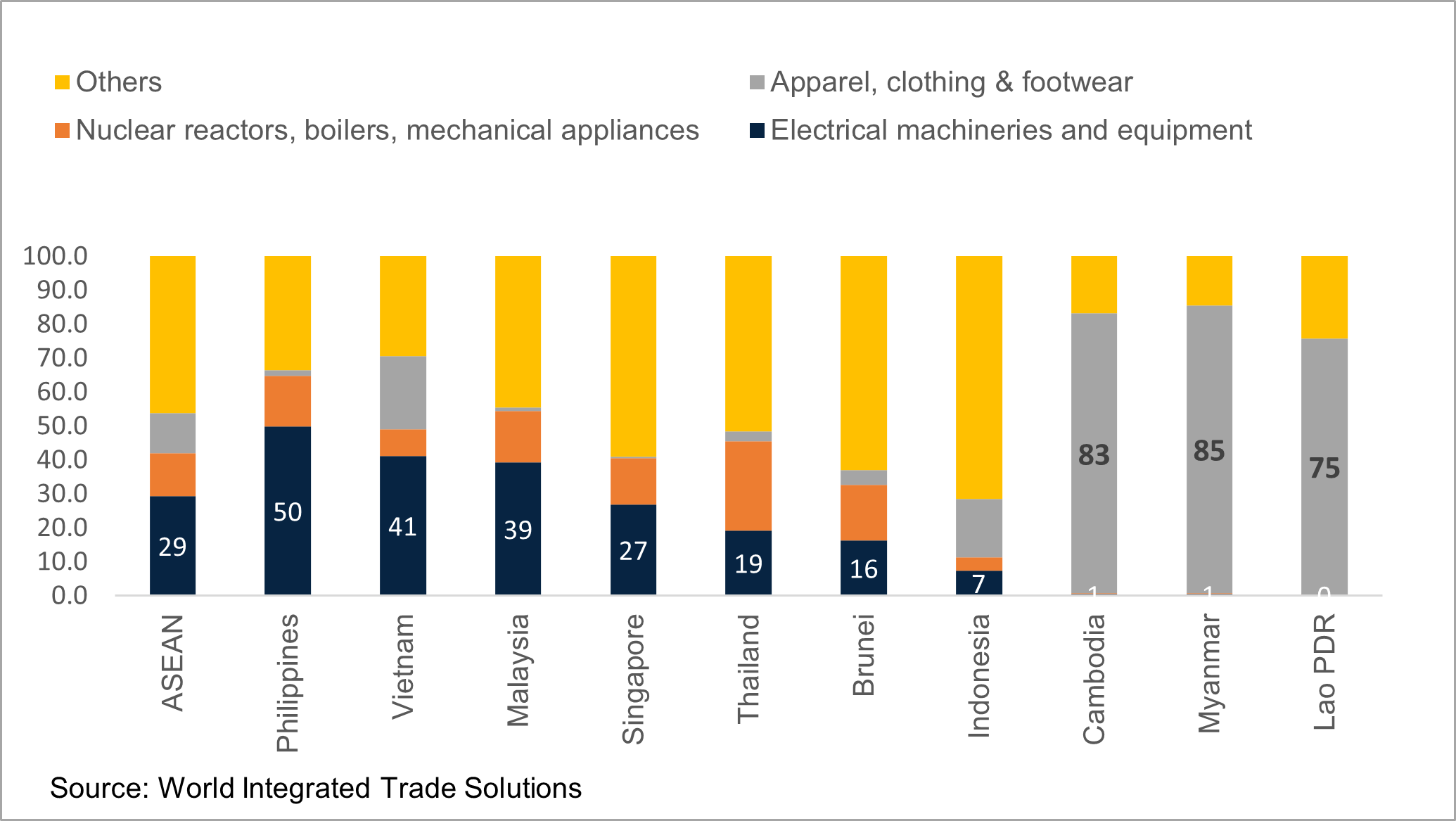

The EU has been an important export destination (third, after China and United States) and investor in ASEAN. However, to make the ASEAN partnership more inclusive, there is significant scope to increase efforts on expanding and diversifying EU’s imports from and investment across ASEAN member states. For instance, based on data from World Integrated Solutions (WITS), the share of EU’s imports from ASEAN to total imports has been relatively low (3%) and stagnant between 2017 and 2021. It has also been lower compared to the share of imports from ASEAN by China (16%) and US (10%) as of 2021. While more than 50% of total ASEAN goods exports to the EU may be considered sophisticated products (e.g., electrical machineries and equipment, mechanical appliances, photographic and surgical instruments), these only comprised less than 1% of the goods exported by Lao, Cambodia and Myanmar to the EU (Figure 2). Sources of EU’s imports from the region are also less diversified. Half of EU’s imported goods from ASEAN came from Vietnam and Malaysia as of 2021 (based on WITS data), while more than 70% EU’s imported services from region are sourced from Singapore (71%) as of 2020 (based on Eurostat data).

Figure 2. Major exports by ASEAN members to EU (% share, 2016-2020)

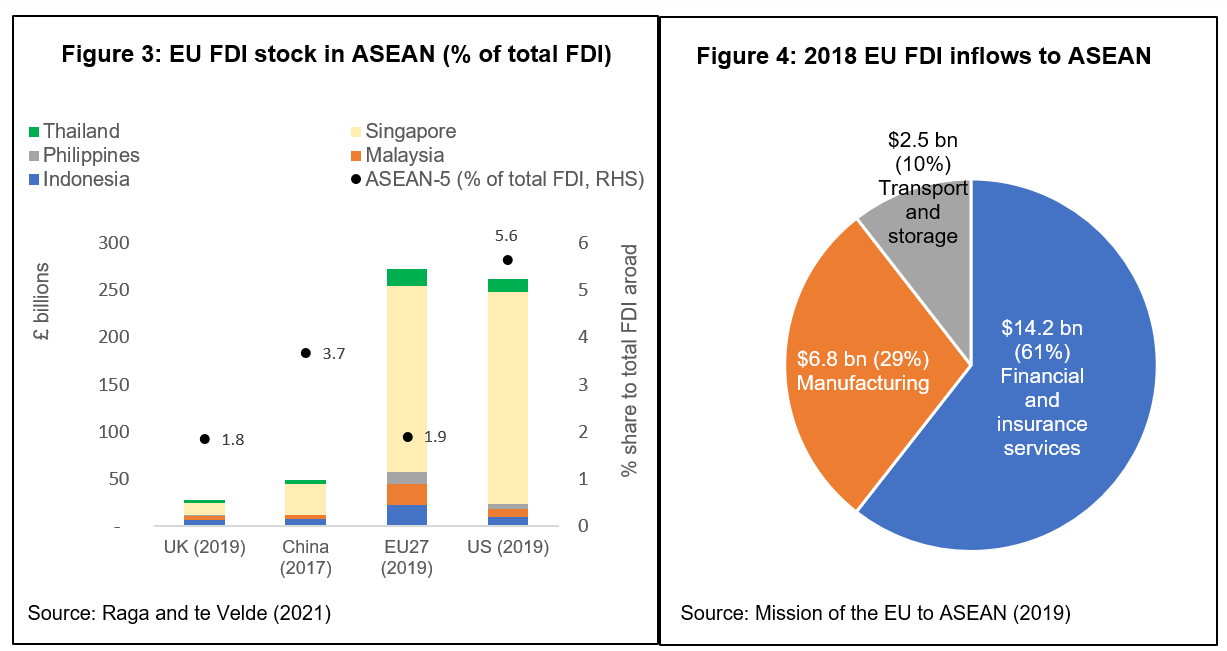

Similar trends appear in foreign direct investment (FDI) stock. Based on EuroStat data, while the value of EU’s FDI stock has increased by 25% to €382 bn between 2018 to 2020, the share of ASEAN in EU’s FDI stock worldwide was only around 2% (lower than the share of ASEAN in FDI of the US; Figure 3). Moreover, EU’s FDI to ASEAN is concentrated in terms of countries and sectors. As of 2020, nearly three-quarters of EU’s FDI in ASEAN went to Singapore alone, only 2% went to BCLMV (Brunei Darussalam, Cambodia, Lao PDR, Myanmar and Vietnam). Investment is also concentrated in financial and insurance services (driven by FDI in Singapore). This persistent preference for Singapore is not exhibited by European investors alone, as in earlier analysis we saw similar trends from UK and US investors.

The EU has reaffirmed its long-term goal of pursuing a region-to-region FTA with ASEAN, in addition to its step-up cooperation efforts in the wider Indo-Pacific implicitly to balance the influence of China in the region, among other development objectives. The EU has existing bilateral trade agreements with Singapore (effective 2019) and Vietnam (effective 2020).

While often overlooked, ASEAN works through consensus of its 10 members. Among the largest multilateral cooperation and agreements today, only the China-led RCEP included Cambodia, Lao and Myanmar (Figure 1). By consciously increasing commitment to boost trade and investment activities (e.g., through facilitation, promotion, capacity building) in the region outside Singapore, the EU and others may reinforce their position as a development partner in helping low and lower-middle income ASEAN members achieve their economic transformation goals, enabling faster engagement with and cooperation from ASEAN as a unit on economic, political and environmental issues of global importance.

Infrastructure competition in southeast Asia

The competition in Southeast Asia also manifests itself in the provision of infrastructure. During the EU-ASEAN Summit, the EU committed to provide US$ 10 billion in development finance to ASEAN countries. However, details on what this covers were not provided, and it may even include some existing projects.

Initiatives such as the EU’s Global Gateway or the G7’s Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment (PGII) aim to reclaim a place lost a long time ago, when the so-called ‘traditional donors’ all but stopped financing infrastructure, and which has since been occupied by China. China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is explicitly the main target of this competition. The EU-ASEAN partnership highlights strategic connectivity as one of its domains, this being also one of the main pillars of the BRI.

This ‘battle of the titans’ seems to leave little space for Southeast Asian countries express their needs. In the rush to offer an alternative to China, the EU and the G7 promote their initiatives as addressing the flaws of the BRI by promoting democratic values and good governance, providing green and clean infrastructure and placing emphasis on social sectors such as health and education. And yet, these initiatives seems to forget that one of the BRI’s greatest strengths is that the engagement is centred around what the host countries (or at least their elites) ask, rather than what China wants. This is what has made the BRI so popular with many developing countries’ governments, and what the EU and the G7 should take a leaf from.

Southeast Asia and the broader Indopacific can benefit a lot from this competition to provide infrastructure. While the world’s richest countries fight to gain the strongest partnerships in the region, southeast Asia enjoys much attention from all sides, and can try to leverage that to its advantage, particularly on mobilising infrastructure financing for lowest income ASEAN members which have the highest infrastructure needs but also the least access to international capital markets.

What should the EU do?

ASEAN countries expressed their disappointment after the summit. Their hope was to fast-track a free trade agreement with the EU, but the leaders’ statement issued post-summit shows that a trade deal remains a ‘common long-term objective’ rather than an imminent reality.

In general, the EU should aim to make its partnership with ASEAN more comprehensive by strengthening its economic and business relations beyond Singapore. At the moment, the strategic partnership looks at the ASEAN as a bloc, but this may not be enough to reach partners like Myanmar, Cambodia and Laos. The EU should put some extra effort to strengthen the relationship with these countries too, for instance by designing tailored programmes of engagement beyond the generic ‘ASEAN’ headlines.

In terms of infrastructure, while the Global Gateway programme is welcome, the EU offer should not be motivated by a desire to compete with China, but rather it should fulfil the double objective of offering what the EU is best placed to provide and what ASEAN countries want from their European partners. If that is not large infrastructure, but rather support on smaller projects, or on governance, development and other ‘soft infrastructure’ matters, so be it. An offer that is just prompted by a desire to compete is not sustainable for the EU.

Finally, the EU should be responsive to what southeast Asian partners ask. If they express the need for increased trade cooperation, this should form part of the discussion. Agreements could also cover investment and financial measure, innovation and climate cooperation and so on. An inclusive and transformative partnership needs to be an equal partnership, where the need of both parties are taken into account.