As people age, many find themselves needing long-term care. This demand among older people is outpacing the growth of the care workforce, with the predicted need for care workers surpassing the entire health sector in some contexts. The scale of this challenge is rarely given the policy attention it deserves, nor is the fact that migration is an effective way to meet long-term care needs.

Ahead of our event hosted by the Centre for Global Development on Migration and the future of care (April 27th) 15:00 BST to discuss our new report on how to harness migrant labour for the care sector, we look at the challenges facing the older persons’ care sector and explain how to expand care migration in an ethical, sustainable, and mutually beneficial way, to ensure older people get the support they need, and workers are able to access quality jobs and adequate labour protections.

The challenges we’re facing

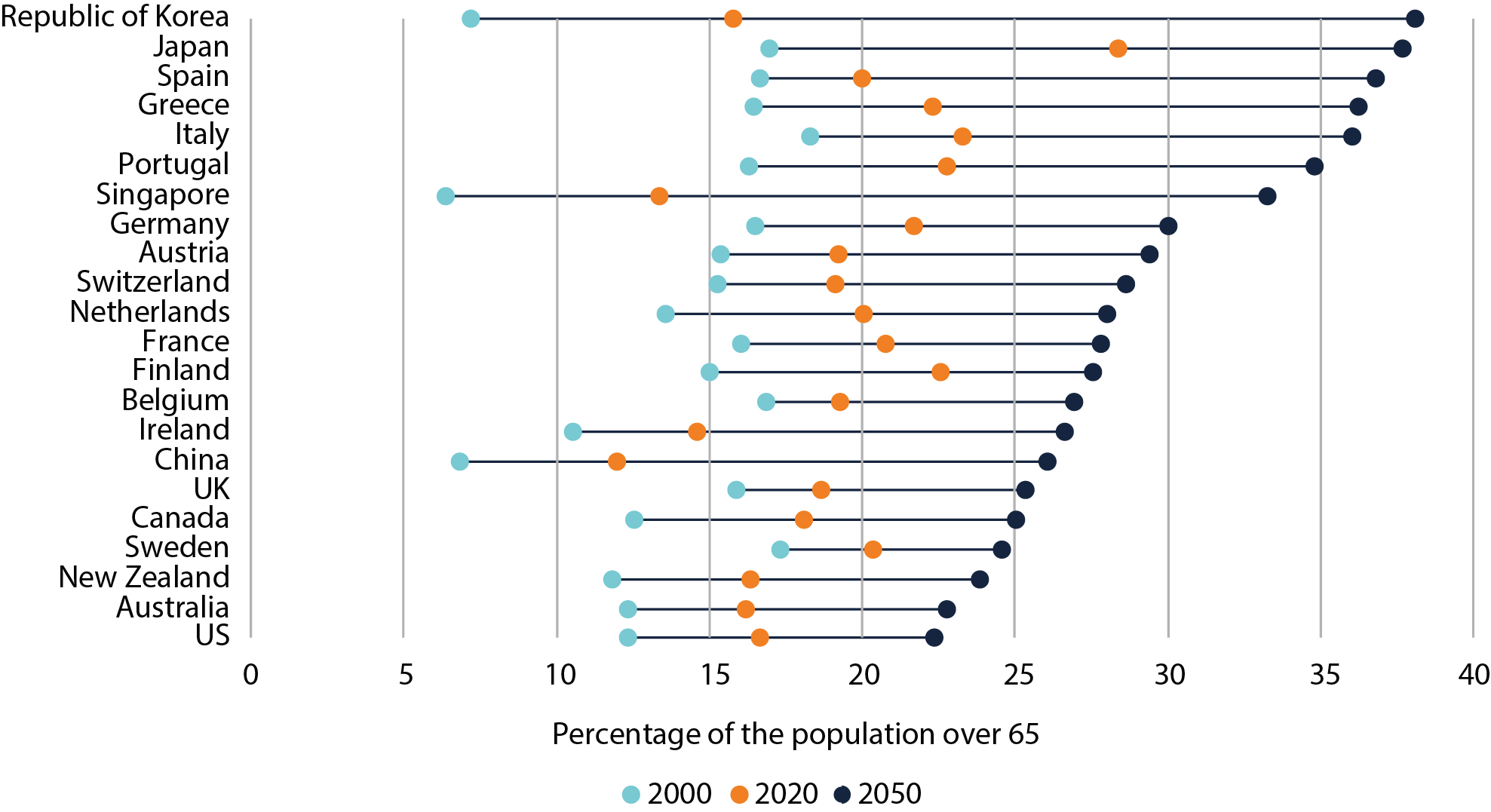

Rapidly ageing societies: rapid ageing is a major challenge for most high-income countries. The Republic of Korea, Japan, Spain, Greece, Italy, Portugal, Singapore and Germany will all have more than 30% of their population aged over 65 by 2050, with many not far behind.

Ageing trends in selected countries, 2000–2050

Note: This figure uses UN DESA estimates for data up to 2020 and UN DESA ‘medium variant’ projections for population ageing by age group after 2020. Source: UN DESA Population Division, 2019

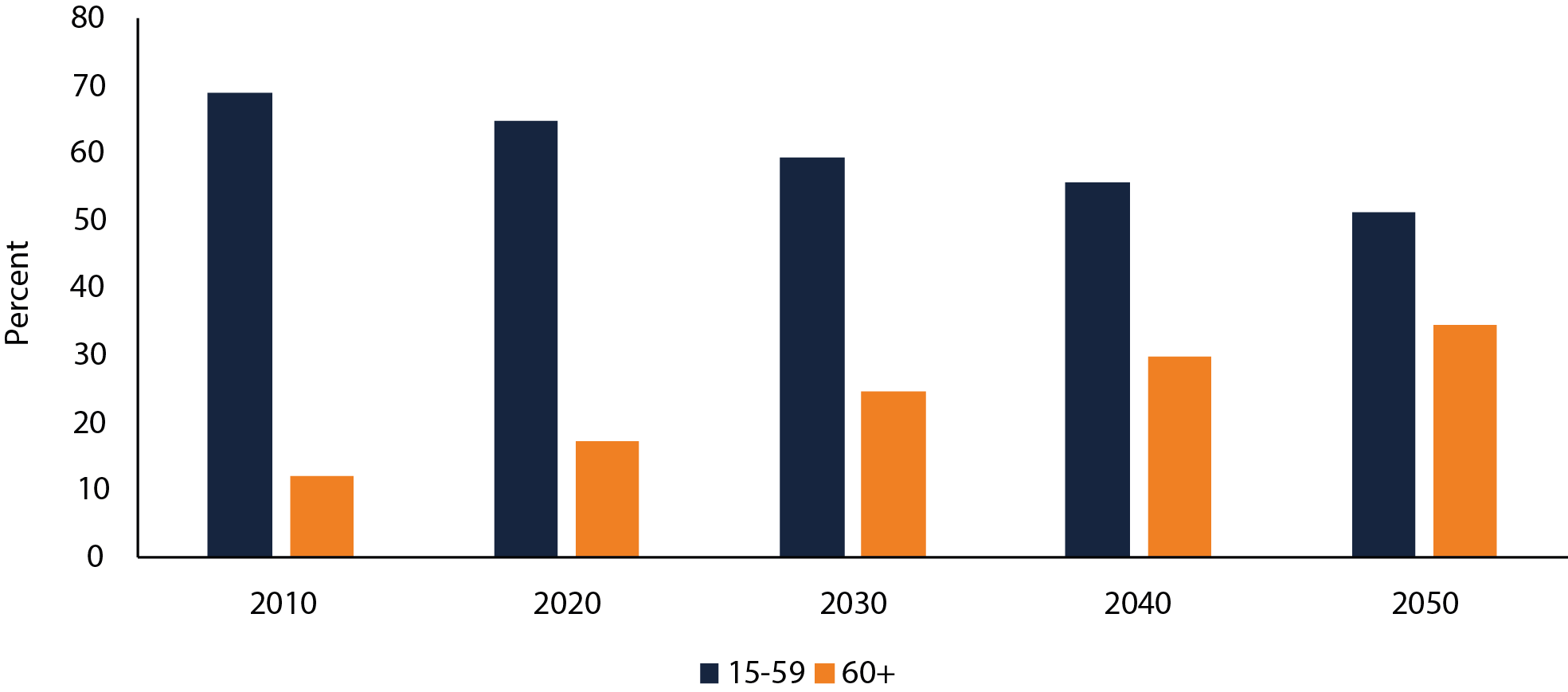

China also merits a mention. It faces a 'demographic tsunami' that will dramatically alter the structure of the country’s population.

Demographic shifts in China, 2010–2050

Note: This figure uses UN DESA estimates for data up to 2020 and UN DESA ‘medium variant’ projections for population ageing by age group after 2020. Source: UN DESA Population Division, 2019

The increasing demand for care: ageing is not the only driver behind this rapid increase. Lower fertility rates, women entering paid work and older people living longer with chronic illness and complex conditions all play a part. Care services have become increasingly important to our economies; in the US, the sector will create more new jobs than any other single occupation in the US economy.

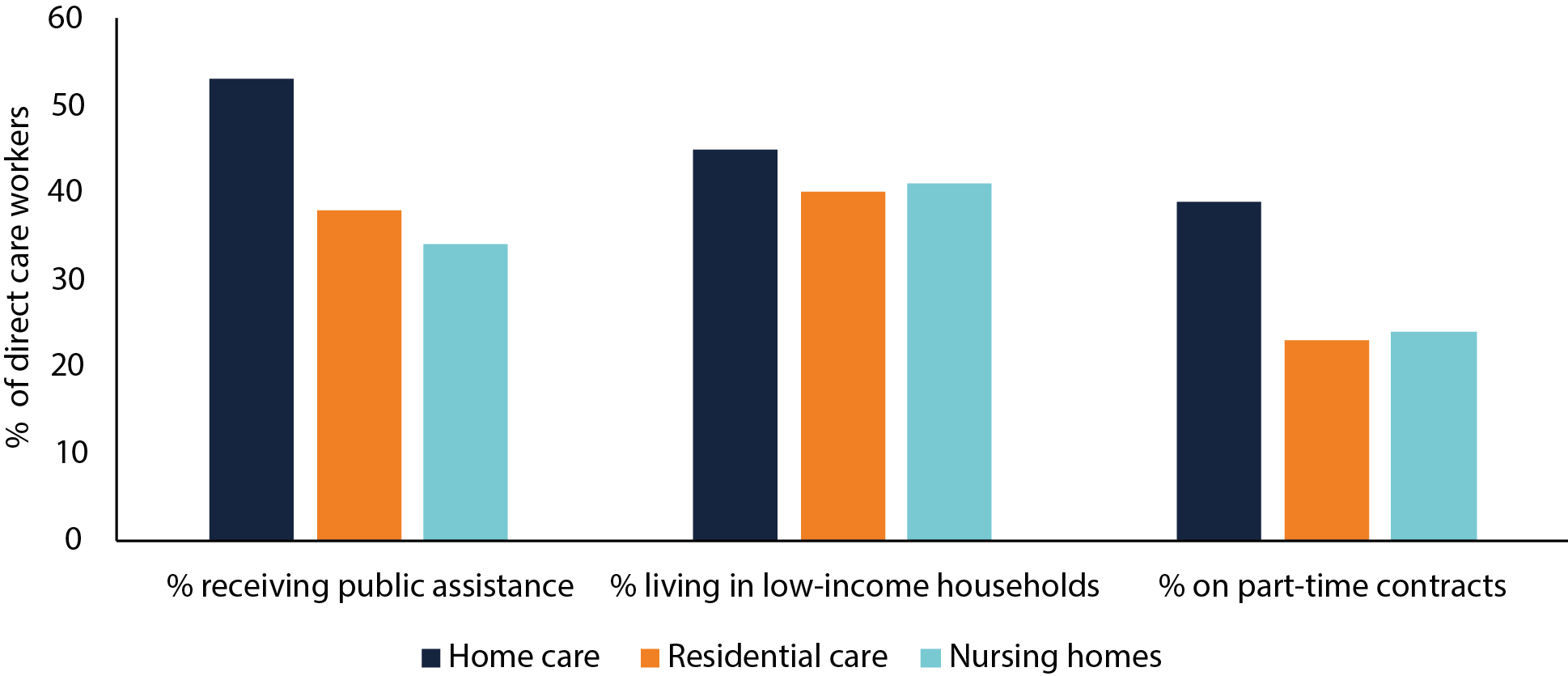

An exploited workforce and a sector in crisis: the sector relies extensively on women workers (90%), who are predominantly middle-aged and very often work part-time. It is notorious for low pay, financial insecurity and low status, no doubt driven by the historic feminisation — and thus undervaluation — of care work (particularly home care).

The financial insecurity of direct care workers (USA)

Source: PHI (2021) ‘Direct Care Workers in the United States: Key Facts’. New York: PHI National

Given the sector’s dependence on public funding, the lack of prioritisation and financing from governments has driven workforce shortages and low-quality care. Austerity, privatisation and marketisation trends have had severe impacts. The UK provides an emblematic example given its extended period of underfunding, highly privatised model of care delivery, precarious working conditions (pdf) and increasing private equity involvement which has resulted in financial instability in the sector. It is increasingly recognised that the dominant role of for-profit care providers and excessive financialization of the sector has delivered both a lower quality of care for older people and poorer conditions for workers.

The sheer scale of workforce challenges: the unattractive nature of care work has contributed to high turnover rates and chronic shortages. Japan has forecast a shortage of 337,000 care workers by 2025. China suffers from an acute shortage, where some estimate that the country needs at least 13 million care workers, compared to the 1 million workers currently employed. In the US, turnover in home care work has reached unprecedented levels, waiting lists are spiralling (pdf) and many simply go without care. In the UK, shortages mean older people remain in hospital, aggravating an already serious health care crisis.

Increased and improved migration as a key policy solution

Governments have various tools at their disposal to respond to workforce challenges. Making the sector attractive to local workers must be central. However, given the scale of existing shortages – and in light of ageing forecasts – immigration will have to be part of the equation.

Policy responses to workforce shortages

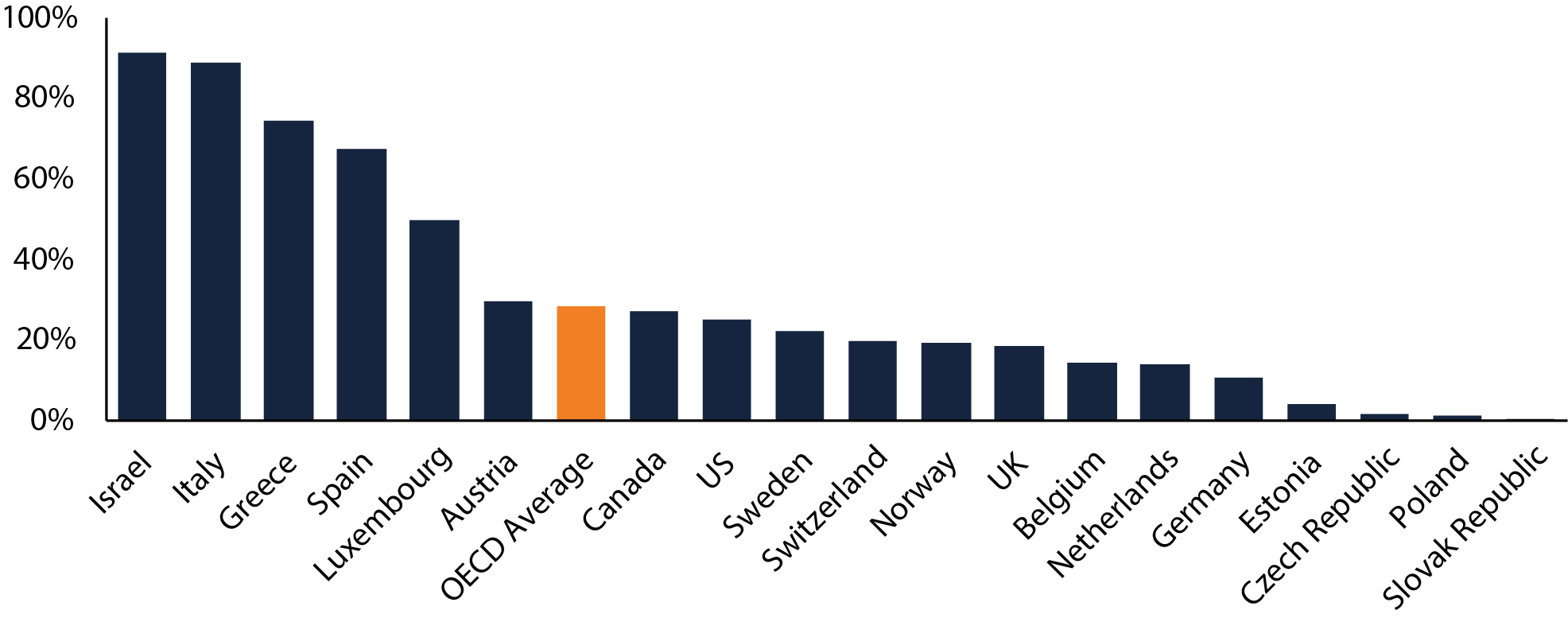

Migrants are already essential to care delivery: more than one-fifth of the long-term care workforce across OECD countries were born abroad. However, migrants’ contribution to home care is often far more substantial. In the context of underdeveloped formal care systems, these workers often make care affordable for people who might otherwise go without support.

Foreign-born workers in OECD home-based care systems, 2013

Source: OECD (2015) International Migration Outlook 2015.

Migrant workers are more likely than local workers to encounter low pay, poor conditions, mistreatment, and abuse, particularly if they are undocumented. The lack of regulation and monitoring of workforce conditions, notable within home care, remains a major gap.

The benefits of migration for older persons’ care

Too often, we fail to appreciate the benefits of care worker migration.

In addition to reducing the heavy burden on overstretched local workforces, evidence suggests that migration is associated with improved quality of care in nursing homes and a lower rate of use of institutional facilities. This serves both the interests of older people by allowing them to stay in their own homes for longer and governments by reducing the costs of long-term care.

Migrants themselves also benefit. Wages are higher than they would typically access in their country of origin and there is comprehensive evidence of the positive impacts that migrants' remittances have in their home countries.

Increasing legal migration pathways for Older Persons’ Care

Most migrant care workers are recruited after arrival in their host country, having entered through free movement agreements or non-labour migration channels (via family, humanitarian, or student visas). Very few countries have specific immigration pathways to attract care workers, though Canada, Israel and Japan provide examples. Canada stands out with its Home Support Worker Pilot (HSWP) which includes a pathway to residency and citizenship. It operates alongside smaller programmes to attract workers to remote areas.

Australia is also exploring ways to use its general labour migration pathway to attract older persons’ care workers to remote areas of the country. And in the US there have been calls to reform immigration policy to attract much needed migrant workers to the home care industry, particularly in rural areas suffering huge workforce shortages.

There is a potential risk that turning to migration could discourage long overdue reforms (including adequate financing) of the sector. However, in the absence of deep structural reform – and facing already critical labour shortages – initiatives that enable ethical and sustainable care worker migration should be an immediate priority.

Achieving the ethical and sustainable international recruitment of care workers

To protect workers’ rights, migration must be accompanied by better regulation and monitoring of recruitment practices, as well as with more appropriate legal pathways for the older persons’ care sector.

This implies new challenges given the lack of professional accreditation standards for care workers and of established regulators, and the need to monitor recruitment activity in the fragmented landscape of multiple private providers.

To increase migration of care workers, in line with ethical and sustainable recruitment standards, we recommend that OECD countries:

● make it easier for care workers to migrate, through general migration schemes and targeted pilot schemes

● ensure pathways provide a tangible benefit to the country of origin in line with the World Health Organisation’s Global Code of Practice on the International Recruitment of Health Personnel

● ensure visas include family accompaniment and are not tied to one employer

● ensure migrants are employed on the same conditions as locals, and have access to training opportunities, alongside establishing the career enhancement pathways and professionalisation of the older persons’ care workforce that is long overdue.

Sign-up to our event, hosted by the Center for Global Development on April 27th, where we will discuss our new report on Migration and the future of care and analyse the intersection between the older persons’ care sector and migration, looking at the experience of migrant workers and the patterns of mobility for older persons’ care between countries alongside an expert panel including Ana Llena-Nozal, Maria Jikjela, Robert Espinoza, and Ito Peng.