Child marriage and female genital mutilation/cutting (FGM/C) are violations of girls’ and women’s rights to health and well-being. Around 650 million women alive today were married before the age of 18, and each year 12 million more girls will be married before they reach 18 (UNICEF, 2021). More than 200 million girls and women around the world have undergone FGM/C, and every year another 4 million are at risk of being cut (UNICEF, 2023).

Significant sums of money are invested in reducing these practices. UNICEF and UNFPA, for instance, have invested $300 million on their Global Programme to Accelerate Action to End Child Marriage and the Joint Programme on the Elimination of Female Genital Mutilation, which is the largest global programme that aims to end the practice.

Despite the large investments, these practices are not declining at the rate desired. For example, in Mali, a country with one of the highest rates of FGM/C in the world, prevalence has fallen by only 2% in two decades – from 91% to 89%, according to recent analysis of Demographic Health Survey (DHS) data by ODI. In terms of rates of child marriage in Mali, progress has been similarly slow. Data from UNICEF shows in the 25 years from 1997 to 2018, there was only a 3% decrease in the practice with 54% of girls being marriage before they turned 18 years in 2018 compared with 57% in 1997.

How can we make sense of these disappointing trends? Is social norms change programming overlooking the latest evidence on who really influences these practices? Could grandmothers, in fact, be pivotal in shifting norms?

What we know about catalysing social and gender norms change

To a large extent, FGM/C and child marriage are underpinned by social norms. These are perceptions that people hold regarding what their peer group – usually members of their family and community – expect of them. Perceptions and expectations are shaped by deeply rooted cultural or religious beliefs including regarding gender roles. To demonstrate the influence of social norms, ODI’s analysis of the DHS data from 2018 shows that, in Mali, ‘peer effects’ – namely the share of girls in the community who have already undergone FGM/C – is one of the strongest predictors of whether a young girl herself will be cut. Even the influence of ethnicity dissipated once peer effects were included in statistical modelling .

Currently, the dominant model informing social norms change programming is the Knowledge-Attitudes-Practice (KAP) model. It assumes that individual changes in knowledge relating to the harms of practices like FGM/C and child marriage will lead to changes in attitudes and later shifts in practice, once a critical mass is achieved at each stage.

However, ODI’s quantitative analysis suggests there may be flaws in this model. Evidence shows considerable increases in knowledge and attitudes in favour of abandonment as a result of campaigns by government and development organisations, but persistently high prevalence of the practices. It would appear that attitudes on average are not decisive for promoting shifts in practice.

An alternative to the individualistic diffusionist KAP model is systems theory, which takes into account the effects of collective expectations and group power dynamics on individual behaviour. Systems theorists argue that, in order for social norms to shift, all people who wield authority over a norm must simultaneously and collectively reach a consensus in favour of change. Attempts to shift behaviour at the individual level, or by focusing on people who wield little authority, are rarely effective. Either these people will face stigma and discrimination for not conforming to the dominant norm or, if they lack authority, will be unable to convince others to follow their example.

Evidence of grandmothers’ authority and decision-making role

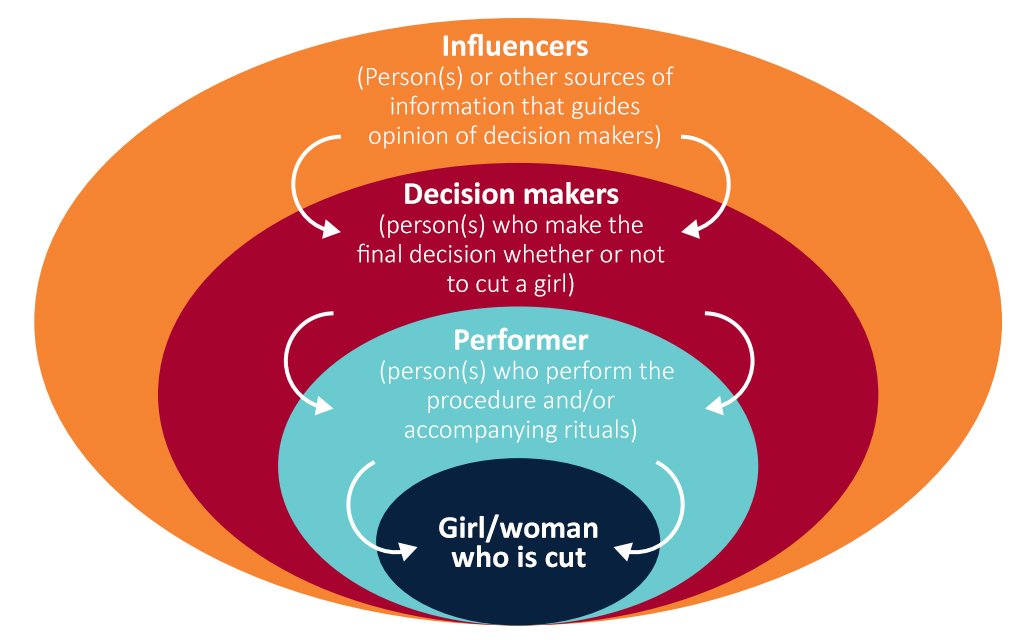

As social norms change requires engaging relevant authorities, one of the essential things that organisations working to reduce FGM/C and child marriage need to consider is who takes decisions, and who wields influence over these practices.

ODI undertook an in-depth literature review and a mixed-methods study in six regions of Mali to understand family and community decision-making dynamics underpinning FGM/C. They sought to identify who carried out the practice and accompanying rituals; who were the decision-makers in the family or community who decided whether and when to cut a girl; and who were the influencers shaping the norms underpinning the practice.

The results of this research painted a consistent picture across all study sites: grandmothers, or female elders, play a major role, and wield significant authority, in all three categories of action.

The results of this research painted a consistent picture across all study sites: grandmothers, or female elders, play a major role, and wield significant authority, in all three categories of action. Because FGM/C is perceived to be a ‘women’s issue’, fathers – and men of reproductive age generally – exert variable degrees of authority over family decisions regarding the practice. They often leave the question of cutting their daughters to the girls’ mother, aunties or grandmother. However, men – including religious leaders – do play an important role in influencing social norms, by advancing religious arguments for continuing or abandoning the practice or through their treatment of (un)cut women.

The important role of grandmothers in shaping social norms that underpin women’s and children’s health has been widely documented throughout the Global South, usually by anthropologists. Yet, global health and development organisations rarely factor that role into social norms change programming. ODI’s review of recent interventions implemented in Mali found that none of the programming explicitly involved grandmothers or female elders. When ‘women’ as a target group were mentioned, their age was usually not specified. When it was, it became clear that younger women aged 15 to 49 were being addressed.

It is possible that organisations do not engage grandmothers because they associate them with support for FGM/C, and therefore assume them to be a harmful influence. However, ODI’s quantitative study found that, in Mali, women and elders were actually slightly more likely than youth to favour abandoning the practice. Furthermore, other categories of people who often support FGM/C and child marriage – like religious leaders – are frequently solicited as change agents, so why not grandmothers?

In support of a grandmother-inclusive approach, Bettina Shell-Duncan, anthropologist at the University of Washington, USA, has recently argued:

Older women are uniquely positioned to realize the dual goal of honouring tradition while negotiating change. Rather than resisting change, we find that some older women express an openness to reassessing norms and practices as they seek solutions to maintaining the physical well-being, moral integrity and cultural identity of girls in their families.

Key principles of grandmother-inclusive social norms change programming

The ‘grandmother-inclusive’ approach was originally developed by the NGO The Grandmother Project. The grandmother-inclusive approach follows these five principles:

- Respect the traditional cultural roles, experience and knowledge of elders, especially grandmothers, and involve them explicitly and respectfully in activities.

- In addition to grandmothers, involve other categories of people who wield authority and influence in a given context, such as men, community and religious leaders, healthcare workers, or teachers.

- While working within traditional structures of authority to shift social norms, it is also important to empower those categories of people who have less decision-making authority – such as adolescent girls and boys, and young mothers – to ensure that their perspectives are heard.

- Use non-directive messaging, namely catalysing dialogue around people’s motivations for FGM/C and child marriage, as well as sharing information which dispels myths such as religious justifications for the practices, but do so without telling people what is ‘right’ or ‘wrong’ or dictating how they ought to behave.

- Facilitate intergenerational dialogue within communities to support them to identify problems, diagnose causes and reach a consensus over the design and implementation of solutions – including shifts in health-related social norms and behaviours.

Following these principles, and given the importance of engaging cultural authorities in order to shift social norms, ODI collaborated with UNICEF Mali and their local partners in designing a Behaviour change toolkit which addresses norms relating to FGM/C and child marriage in Mali.