In late October, the African Development Bank (AfDB) transferred the risk on a $2 billion portfolio of AfDB loans to a group of private London-based insurers and the UK’s Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO).

The loans remain on AfDB’s books and continue to be fully administered by the bank, but the risk of a borrower default is now partially covered by the insurers and FCDO. This creates space for AfDB to make up to $2 billion in new loans. The new lending headroom is a welcome boost to AfDB’s lending capacity, as its annual lending dropped from about $10 billion in 2018 to $6 billion in 2020 and 2021 due to capital constraints.

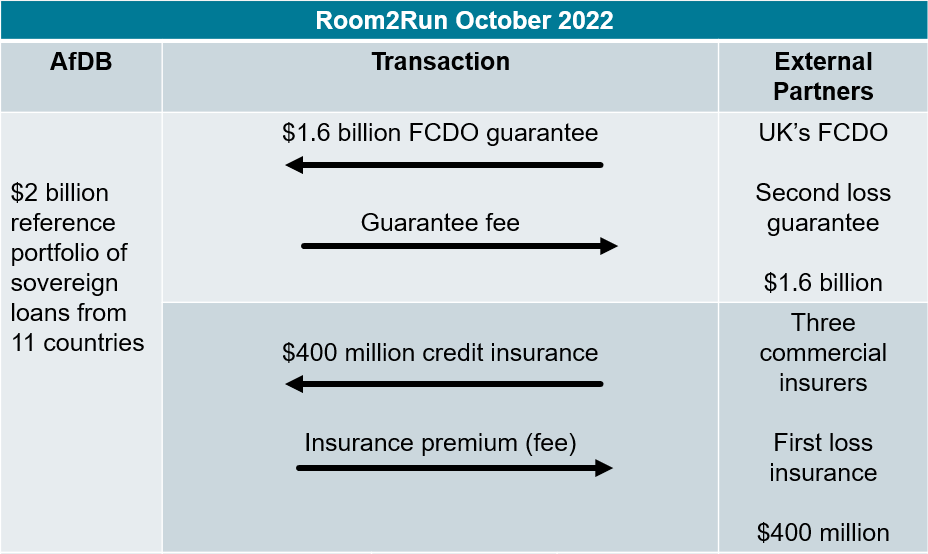

The Room2Run operation (see Figure 1 below) is important both for AfDB and, more broadly, as a pilot for risk transfers by multilateral development banks (MDBs). In recent years, several MDBs have started to experiment with different types of risk transfer operations as a way of creating more lending headroom without needing fresh shareholder capital.

The AfDB deal is particularly noteworthy because it involves commercial investors taking a stake in a portfolio of sovereign loan risk – a first in the MDB space.

Figure 1

What is a portfolio risk transfer?

All MDBs have a fixed amount of risk capital (paid-in shareholder capital plus reserves). For AfDB, this amounted to $10.2 billion as of June 2022. To protect itself in the event of repayment delay or default, AfDB sets aside a portion of risk capital to back up every loan it makes.

The exact amount of risk capital needed for each loan differs across MDBs, but on average, AfDB currently uses $1 of risk capital to back up $3.20 in outstanding loans ($8.5 billion in risk capital deployed versus $27 billion in outstanding loans as of June 2022).

A risk transfer means that the risk of a loan not being repaid is transferred to an external party (e.g. a shareholder government or a private investor) in return for a fee. Since repayment risk facing the MDB is now reduced, the MDB can redeploy risk capital to make more loans. The loans themselves legally stay on the MDB’s books, and the MDB continues to administer and oversee them until the projects are completed and the loans fully repaid. When this is done with a set of loans, rather than just one, it is called a 'portfolio' risk transfer.

So far, MDB risk transfers have mainly been the domain of official agencies such as the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency’s arrangement with the Asian Development Bank in 2016 and several subsequent arrangements between other donor governments the World Bank. However, donor willingness is a limitation, and MDBs also need to be cautious that donor policy priorities do not unduly influence MDB governance and operational strategy. AfDB did the first two MDB portfolio risk transfers with private investors (with some donor support) in 2018, freeing a total of $1 billion in new lending headroom.

More recently, portfolio risk transfers were included in the recommendations of the G20 Independent Review of MDBs’ Capital Adequacy Frameworks. They were also the topic of an ODI event in October 2021.

AfDB’s deal the first with sovereign loans and private investors

A key issue limiting MDB risk transfer – especially for loans made by MDBs to government borrowers (‘sovereign’ loans) – is the cost. MDB sovereign loan interest charges are well below market rates due to the cooperative nature of MDBs. The cost of transferring the risk of sovereign loans to commercial counterparties may be greater than what the MDB earns on the loans – not a financially efficient way of creating more lending headroom. This is less problematic for official guarantors like the Swedish or UK governments since they can subsidise the risk transfer fee. Risk transfer cost is also less problematic for loans made by MDBs to private sector borrowers (as in the 2018 AfDB deals) because these loans are priced closer to market rates and therefore generate more loan income to the MDB.

The recent AfDB operation combined a UK government guarantee with a commercial risk transfer to private insurers. The resulting total pricing enabled AfDB to move ahead with this first deal involving MDB sovereign loans and commercial counterparties.

The risk transfer is split 20%-80% between the private insurers (AXA XL, HDI Specialty and Axis Specialty) and the UK’s FCDO, and covers a total of $2 billion for 11 countries in AfDB’s sovereign loan portfolio. If one of these countries goes into arrears on its loan repayments, FCDO and the private insurers will pay AfDB instead. Once the guarantee amount for the country in arrears is used up, AfDB would cover any remaining losses itself.

FCDO and AfDB agreed that new lending will be dedicated to climate finance and split evenly between adaptation and mitigation, with any AfDB borrower eligible. Speaking to ODI, AfDB’s Manager of Syndication and Co-Financing Max Ndiaye, who led work on the deal, noted that this redeployment focus aligned well with overall shareholder-defined AfDB objectives as a cross-cutting issue across the bank’s five core priorities.

Preferred creditor treatment and risk transfer pricing

One unique feature of MDBs is that government borrowers very rarely fall behind on repaying their loans, and when they do, those arrears are always eventually cleared. This is the basis of preferred creditor treatment (PCT) underpinning the extraordinarily strong loan portfolio performance of MDBs. Borrower governments view MDBs differently from commercial creditors, because of their official status, development mandate and cooperative nature.

This raises the question of exactly what repayment risk is being covered in risk transfer deals on sovereign loans, and how much insurers and FCDO should be paid. If sovereign loans never default and are always eventually repaid (albeit with occasional delays), the risk is very low and the risk transfer fee should presumably also be minimal. Due to PCT, risk transfer for MDB sovereign loans should arguably be possible on a commercial basis without the need for FCDO’s additional subsidy.

However, the informal nature of PCT (it is not in any loan contract and has no legal status) and the lack of publicly available MDB loan performance data make this difficult. A further consideration is the opportunity cost for the insurers, who might be able to find more profitable deals (such as commercial bank loan portfolios in the same African countries).

AfDB’s sovereign loan charge is currently 0.8% over its own cost of funding. According to Ndiaye, the overall cost of the risk transfer – combining the subsidised FCDO and commercial insurance portions – was below 0.25%. The unlocked resources therefore not only increase the bank’s lending capacity but also positively impact its revenue generation through future lending income.

While the pricing meant that this deal made sense for AfDB as a financially efficient way to create more lending headroom, it does not necessarily follow that the pricing fairly reflected the strength of AfDB’s PCT. The insurance firms may very well be getting an excellent deal. The fee portion charged by the firms was not made public.

According to Simon Bessant of Texel Group, AfDB’s insurance broker for the Room2Run Sovereign transaction, access to uniformly-reported portfolio performance data across a range of MDBs would help price MDB loan risk more accurately. One particularly useful step would be to make the Global Emerging Markets (GEMs) database of MDB loan performance more widely available, as recommended by the recent G20 independent panel.

Risk transfer on sovereign loans across MDBs could be problematic for reasons beyond the pricing issue if they are done systematically and at a more substantial scale than the modestly-sized AfDB deal. The attraction of shifting MDBs to an ‘originate and distribute’ model of making loans and then offloading them to investors is obvious: it reduces the need for capital, which comes from shareholder government budgets. However, if a substantial share of the repayment risk of sovereign loans is no longer held by the MDBs, but rather by a private investor, the basis for PCT could erode. MDBs might come to be perceived as dealmakers for investors rather than as official development agencies.

Ndiaye clarified that this is not a problem in the recent deal, first due to the small size of the transaction and second because AfDB always remains the lender of record and retains a substantial portion of the portfolio risk on each set of country loans. He stresses that AfDB views financial innovation like Room2Run as a means to supplement capital and not as a substitute for a general capital increase, in line with the G20 independent panel recommendations and an analysis of MDB risk transfer published last year.

Risk transfer: a useful tool, but not a substitute for shareholder capital

The AfDB Room2Run sovereign transaction is an important step for development finance, and other MDBs, shareholders and private market actors would do well to examine it closely. Portfolio risk transfer operations are a useful tool for MDBs seeking to increase their capacity to address pressing development needs, and can serve as an effective mechanism for mobilising private investors. That said, they are not a viable substitute for fresh shareholder capital to align MDB financial capacity with development objectives.

The transfer of risks embedded in sovereign MDB loans to external parties is well worth exploring, but three considerations should be kept in mind:

- Guarantees from development agencies could give the donor government undue influence in steering an MDB’s lending. Risk transfers should closely align with shareholder-defined overall MDB objectives, as is the case with the UK’s support of Room2Run. Targeting specific sectors and geographies prioritised by an individual donor could have negative MDB governance implications.

- For commercial sovereign loan risk transfer, pricing should adequately reflect the extremely safe nature of MDB sovereign loans. Otherwise, MDBs could in effect be subsidising investors.

- MDBs should exercise caution in sharing their PCT with private investors, as it represents the unique status of MDBs as non-commercial development cooperatives. This is not a concern in AfDB’s recent deal due to its modest size, but it could be problematic if an MDB were to scale up risk transfers systematically as a substitute for shareholder capital.

Transferring the risks of non-sovereign MDB loans is more straightforward and would make sense to scale up as an effective technique to mobilise private investors. PCT is less of an issue and pricing is easier to manage. Non-sovereign risk transfers can help commercial investors get more comfortable with sectors (e.g. sustainable infrastructure) and geographies (e.g. lower- and middle-income countries) where risk perceptions may be exaggerated. It would therefore make sense for private sector-focused MDBs like the International Finance Corporation and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development to make greater use of these operations as opportunities arise to increase lending capacity.

For all portfolio risk transfer operations, the first step is for MDBs and their shareholders to be clear on the reasons for undertaking these transactions and the appropriate circumstances and financial parameters for a deal to make sense. Risk transfers should not be undertaken simply as a reaction to insufficient shareholder capital, but rather as part of a thought-out strategy for how MDBs can be most effective and efficient.

The second step is to design better templates for risk transfers to reduce the time and costs of arranging the transactions, and to improve their pricing. That will happen over time, as all the main parties to the transactions – MDB staff, commercial investors, ratings agencies and shareholders – become more accustomed to structuring these deals and MDBs make more loan performance data available. Collective work by a group of MDBs to structure standardised deal templates, which can then be taken off the shelf and tailored to address individual MDB and market circumstances as needed, would help.