Breaking the barriers refugees face going from humanitarian assistance to the national protection system

During 2015 and 2016, more than a million refugees and asylum seekers, mainly from Syria, travelled from Turkey to Greece in hopes of reaching other European countries via the western Balkan route. But in 2016, the Greek-North Macedonia borders closed—significantly reducing the number of those continuing to other EU countries by crossing through the Balkans. This left approximately 57,000 people stranded in Greece with limited legal pathways out of the country. At the same time, an agreement between Turkey and the EU—requiring all new undocumented migrants crossing from Turkey into Greece be returned to Turkey—drastically reduced further migration movement. Despite this agreement, the number of refugees and asylum seekers in Greece remained high during the following years, with only 2,000 individuals returning to Turkey, and over 56,000 new arrivals between July and December 2019. During the COVID-19 period flows were further reduced, with less than 10,000 individuals entering the country since April 2020.

In an effort to remain in Greece legally, many of those stranded chose to apply for asylum. Asylum applications in Greece rose from about 10,000 per year before 2015 to over 50,000 in 2016 and reached more than 77,000 in 2019. In 2019, 17,355 people were recognized as refugees, up from 15,192 in 2018 and 10,351 in 2017. The number of asylum seekers and refugees in Greece was unprecedented, placing considerable pressure on a Greek asylum system that was already characterised by significant structural flaws. Since the country was also going through a severe economic crisis, it simply was not in a position to deal with the emergency.

To alleviate the economic and humanitarian pressures brought on by the crisis, the Greek government requested financial and technical assistance from the EU. From 2015 to 2021, the EU allocated Greece more than 3.1 billion euros. The European Asylum Support Office (EASO) and Frontex—the European Border and Coast Guard Agency—also responded with much needed support in handling asylum applications and patrolling land and sea borders.

In Greece, humanitarian assistance through cash assistance and accommodation for refugees and asylum seekers is mainly provided by the Emergency Support to Integration and Accommodation (ESTIA) Programme. Cash assistance is provided by UNHCR in cooperation with international and local NGOs. In March 2021, close to 64,500 eligible refugees and asylum-seekers received cash assistance in Greece. Rented housing is funded by the EU and provided to more than 20,000 asylum seekers by the Greek Ministry of Migration and Asylum.

As an asylum seeker, a person has access to both accommodation and cash assistance. However, once an asylum application is approved, and the individual is recognized as a refugee or beneficiary of subsidiary protection, they are no longer eligible for humanitarian assistance. For those already hosted in apartments of the ESTIA programme, the latest law (L.4674/2020) stipulates that they must vacate their premises within 30 days. This creates a significant protection gap once a person is granted refugee status in Greece.

For refugees, accommodation support is provided through the HELIOS programme, funded by the European Commission and implemented by the International Organization for Migration (IOM) in close collaboration with the national authorities. However, when compared to the actual needs, its scope is rather limited. Close to 8,500 individuals were benefitting from HELIOS rental subsidies in May 2021.

This has caused immense difficulties for those, who as refugees, should be fully protected. Refugees often end up without shelter or any source of income and find themselves homeless in Athens and other cities, with limited access to basic services such as food, healthcare, and education for their children. Many even choose to move in or near reception facilities to have a place to sleep.

A protection gap also exists in the challenges refugees face when transferring from humanitarian assistance to the national protection system. In principle, beneficiaries of international protection have the same rights to access and benefit from the national social protection system as the host population–including the Guaranteed Minimum Income, rent subsidies, child benefit and unemployment or disability benefits.

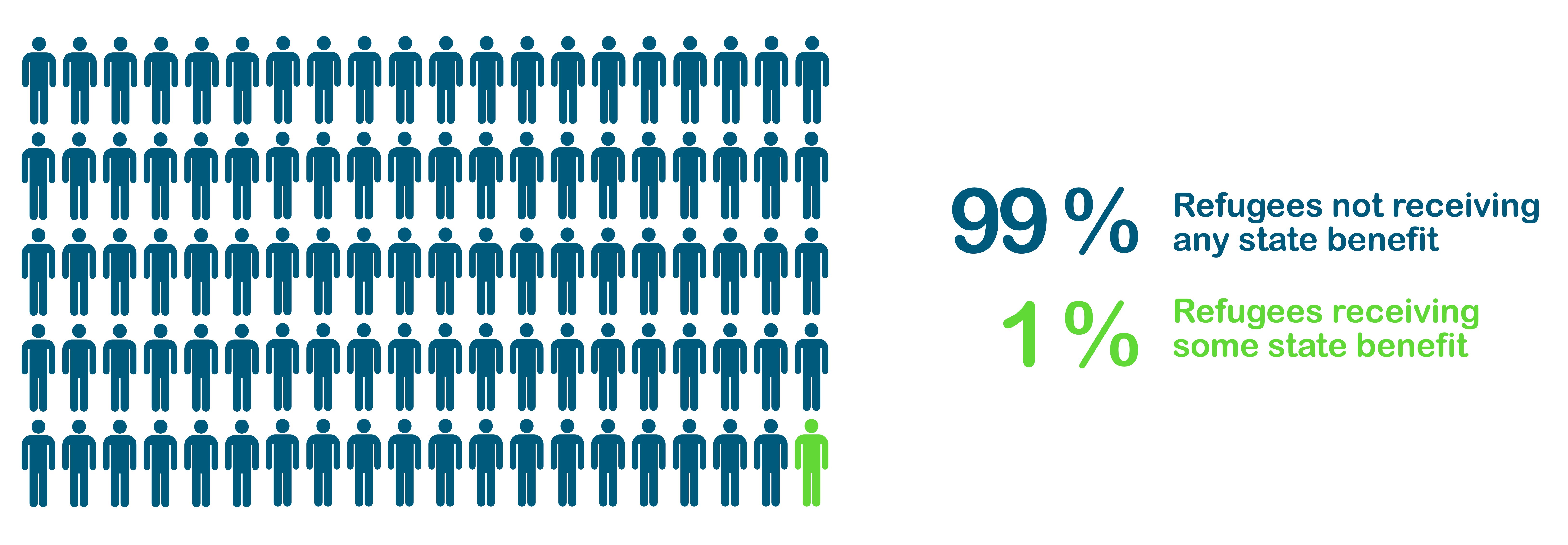

However, preliminary findings by the Social protection responses to forced displacement project, based on research in Greece, suggest that refugees are either unaware of these programs, or they face significant entry barriers to accessing them. Often, they lack a social security number, a tax registration number or a bank account— prerequisites for registering in the state benefits programs. A survey conducted during our research found that out of 310 refugees interviewed in Attiki and Ioannina regions, only 2 individuals were receiving any form of state benefit.

Undoubtedly, the Covid-19 pandemic and the successive lockdowns have further impeded the prospects for refugees and asylum seekers, as it becomes increasingly difficult for them to communicate with NGOs, who could provide information and guidance.

These findings indicate that a crucial protection gap exists for the refugee population in Greece. Paradoxically, in gaining refugee status individuals are less protected compared to asylum seekers. This situation is likely to deteriorate further, since significant budget cuts are expected in the assistance provided by the EU in the coming years.

Going forward, concrete and well-targeted efforts are urgently needed from the Greek government. This could include widening the scope of the HELIOS programme; providing an adequate transition period for recognised refugees to exit the ESTIA programme; prioritising and facilitating labour market integration; and removing entry barriers for the registration of refugees in state benefits programmes. These efforts could help to better protect refugees and to facilitate their transition from humanitarian assistance to the national system of social protection.

Angelo Tramountanis is a researcher at the National Centre for Social Research (EKKE).

This work is part of the World Bank programme "Building the Evidence on Forced Displacement: A Multi-Stakeholder Partnership''. The program is funded by UK aid from the United Kingdom's Foreign, Commonwealth, and Development Office (FCDO). It is managed by the World Bank Group (WBG) and was established in partnership with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR).