To effectively address the complex challenges they face, public bureaucracies, including international development organisations, often need to do more than implement predetermined plans. They need to work adaptively: testing different policies to see what works well, less well and why, and continually learning and iterating policies accordingly.

The Covid-19 pandemic provides a particularly vivid illustration of the importance of dynamic policy responses from government. Yet, very often these bureaucracies are too bureaucratic: their own processes, structures and incentives are key barriers to adaptation.

As part of the LearnAdapt programme, we have explored what an ‘adaptive bureaucracy’ may consist of. In a recent working paper and event, we ask: how can large public organisations, and political and bureaucratic leaders, design policies, report on results, contract services and recruit in ways that enable, rather than inhibit, effective adaptation?

Building on that work, in this blog we have invited four global and cross-sector perspectives, from development, academia and the donor community to reflect on this question and share their insights on how to nurture more adaptive bureaucracies.

Governments are charged with creating positive outcomes in the world, but the challenges governments face are complex.

So, if you care about outcomes, you have to care about complexity.

A crucial lesson complexity can teach us is that outcomes are not delivered by organisations or programmes, they are produced by whole systems.

Complexity shows us that a single organisation cannot be accountable for any one outcome or result. Any social outcome is the product of hundreds of factors working together.

This means our tendency to manage programmes using outcome targets is unrealistic, and can even undermine the results it’s trying to achieve.

So, what happens if we try to manage by outcomes?

Luckily, this is something we can speak about with confidence, as the amount this approach is used means we’ve got lots of evidence.

Managing by results creates gaming of the system. It turns everyone’s job into producing good looking data which reflects those results — rather than concentrating on what actually needs to be done.

Programmes end up producing excellent data, but it can’t be trusted or used, so it undermines learning.

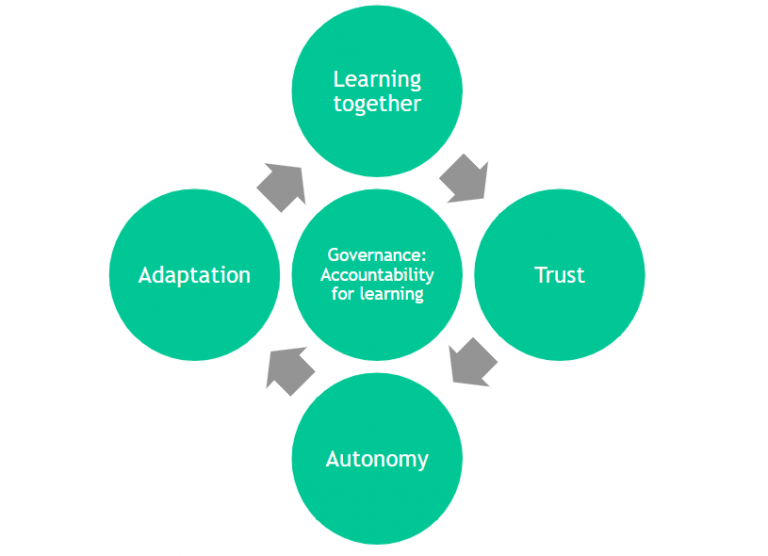

How, then, can we build real learning so programmes can influence the system towards outcomes?

Start by recognising the world is complex, then build human, learning systems.

While working with the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO), we used the Centre for Public Impact’s ‘human learning systems’ lens and found the key was:

- Management that optimises for learning, not results

- Learning together builds trust between people and organisations

- Trust creates space for experimentation and adaptation (which allows a dynamic response to the ever-changing nature of the world)

- Ongoing adaptation requires learning together…. And so on.

A human, learning, systems approach creates better value for money than a results-based programme. We generate better outcomes, cheaper, because we enable those who know best to keep doing the right thing, even as the right thing constantly changes.

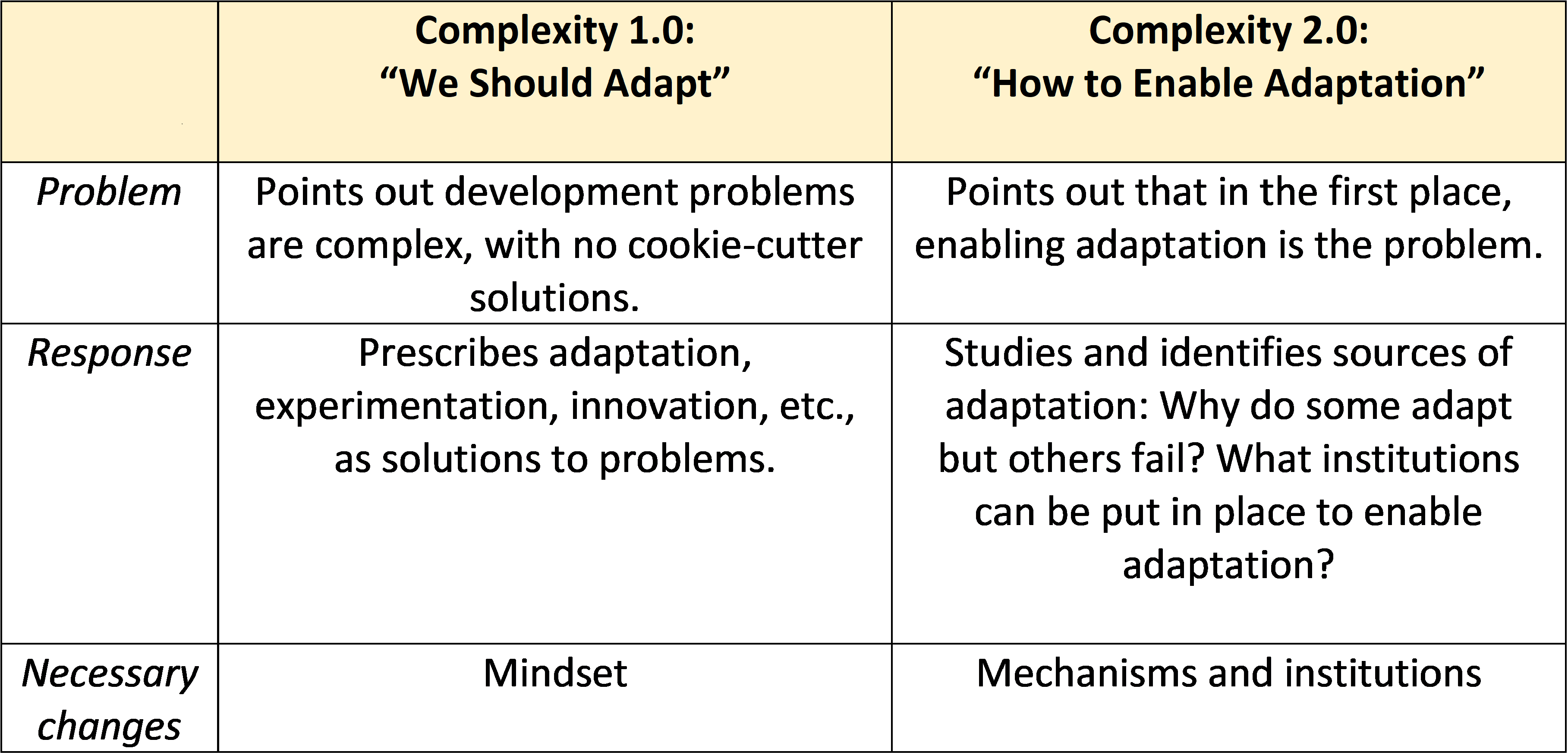

Even before Covid-19, aid agencies and government bureaucracies recognised that development problems are complex, with no cookie-cutter solutions. This has inspired a proliferation of guidebooks, blogs, and programmes that exhort bureaucracies to adapt, experiment, innovate, tailor solutions to local contexts, think outside the box, and so forth.

Although this is an encouraging shift of mindset, it is not enough to enable adaptation.

Wishing to adapt is not the same as being able to adapt. Experimentation and muddling through may not produce useful solutions. Bottom-up participation may degenerate into shouting matches and gridlock. Worst of all, ’adaptation’ and ’innovation’ risk becoming a new-age burden imposed on already overstretched bureaucracies.

If the existing paradigm is Complexity 1.0, I propose Complexity 2.0: moving the focus from agreeing that we should adapt to enabling adaptation.

Enabling adaptation means not just changing mindsets, but also mechanisms and institutions. Here are three examples:

- How are staff members evaluated? If they are encouraged to adapt, is this reflected in evaluation criteria and systems? Or are they evaluated using the same-old criteria?

- Contrary to popular belief, enabling adaptation is not simply about ‘letting go of control’ and allowing bureaucrats to try out anything they wish — rather it’s about deciding which rules must be enforced and when or where discretion should be granted. Specifying ‘red lines’ assures bureaucrats that they can adapt, but within certain guardrails.

- If bureaucrats should not be using template solutions, then how can they know whether they are adapting appropriately? Managers may not be able to immediately answer this question, as they are also learning, but eventually they must signal what success looks like.

Adaptive management demands rigour, which means conducting research and delivering evidence. Adaptive rigour does not mean creating new jargon, fancier charts, or more complicated log-frames. Practitioners should be working with researchers to study what adaptive bureaucracies look like in practice and the mechanisms that enable them. Just as randomised control trials could not take off without a robust research industry on experimental methods, adaptive management cannot be sustained without a research and empirical foundation.

For bureaucracies to adapt, staff need to know they are authorised to adapt and how to adapt.

Authorising happens when the culture of an institution makes space for staff to acknowledge that something unexpected has taken place and to respond to it. An institution’s processes show how to adapt by outlining the steps from where they are to where they need to be. Staff members fill in those steps with adaptations based on their accumulated knowledge and experience, channelled via collaborative analysis.

At USAID, we’ve invested a great deal into culture and processes.

Over the years and through a wide range of formal and informal initiatives, our culture has come to terms with the reality that successful development does not come from creating a detailed strategy or plan and then sticking to it regardless of what happens. We no longer blame the plan when reality takes a turn we didn’t anticipate, and we receive unexpected results. Instead, we acknowledge the many unknowns, that we need to be ready for inevitable disruption, and that we don’t know everything about achieving development results even in the most stable of contexts, let alone more volatile ones. Leaders and staff alike have built into our policies, processes, and programs the expectation that we will need to adapt and the means to do so.

On the process side, this has implications for everything we do. From building a learning focus into plans and programs to understanding change as it takes place. To policy guidance and tools to course correct — altering work plans, timelines, and funding structures — and monitoring methods to track our progress even as we adapt.

Leadership, working norms, and how we trust and support each other are all essential. People in development have a passion for creating positive change, alongside a wealth of knowledge and experience on what to do when Plan A doesn’t work. We need to acknowledge their expertise and let them know we trust them, equip them with clear but flexible guidance and practical tools and support them in bringing it all to bear on high-level goals. It’s that simple and that complex.

Our research at ODI explores how public organisations across a range of sectors and countries have enabled organisational space for adaptation. The examples we include are diverse – ranging from China’s widespread policy experimentation to Plymouth City Council’s customised approach to provide services for vulnerable adults – but they share some common principles.

Firstly, how policies or interventions are designed is key.

Adaptation is never just trial and error. Experimentation and learning are structured and incentivised. Organisational leaders must provide direction in a manner that does not curtail the flexibility needed to experiment.

Some approaches use high level policy steers, which clearly communicate when and where adapation and experimentation are expected, and where they aren’t.

Others employ a structured process for testing and learning, one that guides bureaucrats through the process of reflecting and gathering evidence on whether programmes are performing and adapting accordingly.

Secondly, working adaptively requires greater hands-on management.

Specific skills are needed to be an adaptive programme manager. Staff must be comfortable with uncertainty, and able to innovate, experiment and learn. The job evolves from imposing controls and delivering against plans, to creating effective learning environments, building relationships and trust. All of which requires time and resource.

Often in aid programming management time is seen as something that should be minimised – the more expenditure out the door with limited management overhead the better. But this is not the case for effective adaptive management. Good management is key for programme effectiveness, and it is resource-intensive, at least in terms of time.

Among the aid agencies ODI research has explored, leadership is usually supportive of adaptive ways of working on paper. However, very often the kinds of resourcing and governance processes that are needed to enable adaptation, as Yuen Yuen has suggested above, are either inadequate or lacking. Leadership needs to not just create formal space for adaptive practice, but also provide the kinds of incentives and resourcing that will enable bureaucrats to adapt effectively.