One year ago, as the UK and much of Europe went into lockdown, we committed to monitoring the situation of migrant workers as the pandemic unfolded across the globe. Most importantly, we wanted to bring to life the stories of migrants’ contribution to the Covid-19 response around the world, while also recognising the risks they were exposed to.

We expected to see governments take rapid action to confront the crisis, and we were not wrong. Throughout the pandemic, countries have scrambled to reform restrictive immigration rules, often obliged to fast track much needed migrant workers into essential workforces. These rapid and often effective fixes demonstrate that – regardless of today’s increasingly polarised debates – migration policies can and do change when necessary. It is now on all of us to make sure these changes are long lasting.

All of the information we have gathered in this past year is presented in our innovative data visualisation, created by the information designer Federica Fragapane and developer Alex Piacenti, alongside our accompanying working paper. With their expertise we have sought to harness the power of design to tell the stories of migrants’ contribution across the globe, in real time. One year on from the creation of this data visualisation, we are in a position to take stock of what we have found.

A visible truth: migrant workers are essential workers

The Covid-19 pandemic has provided the most compelling insight yet as to how reliant we are on migrant workers. This is far from a new story. Before Covid-19, OECD countries, in particular, were already exceptionally reliant on migrants, with the healthcare sector an emblematic example. In Luxembourg and Australia, for example, prior to the pandemic over 50% of doctors were foreign born. In London, almost half of doctors and two-thirds of nurses were migrants.

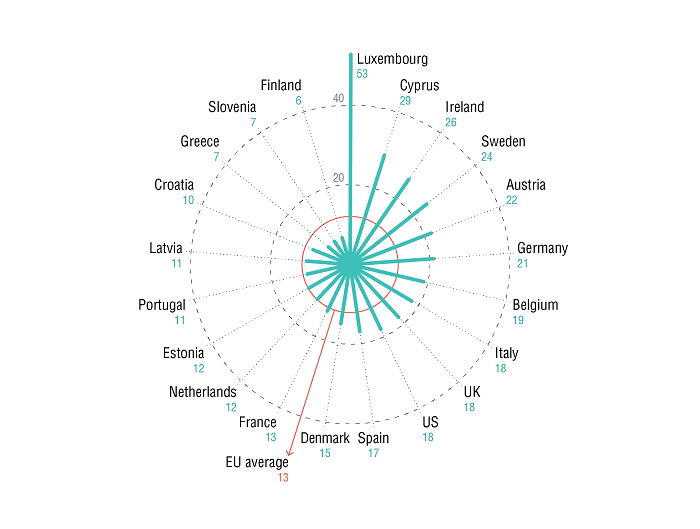

What the pandemic has changed is visibility and general awareness of the vital role these workers play. Suddenly we experienced a genuine moment of reckoning: our economies and societies simply cannot function without ‘key workers’. These are the 'heroes’ – from nurses to care home workers to delivery drivers and supermarket staff whose jobs keep us, quite literally, alive. What is indisputably clear is that migrants figure prominently amongst these workers. Globally, migrants make up only 4.7% of the workforce, but they are far more important when we analyse workforces by ‘essential’ functions (see graphic).

Share of migrant workers in the essential workforce

‘Low-skilled’, ‘irregular’ AND ‘essential’?

Migrant workers may be highly trained doctors, scientists and engineers. But they are also particularly over-represented in the key worker occupations providing vital care and support services we tend to label as ‘low-skilled.’ This often implies unsocial hours, shift work and low pay.

That migrants suffer these disadvantages is not news. However, the events of last year should prompt a significant reflection: can the label of ‘low-skilled’ ever be compatible with a classification of ‘essential’?

We are convinced this is a critical moment for countries to finally detach their immigration policies from outmoded, unhelpful skills-based categorisations and create new legal pathways for all essential occupations, including those that are low-paid.

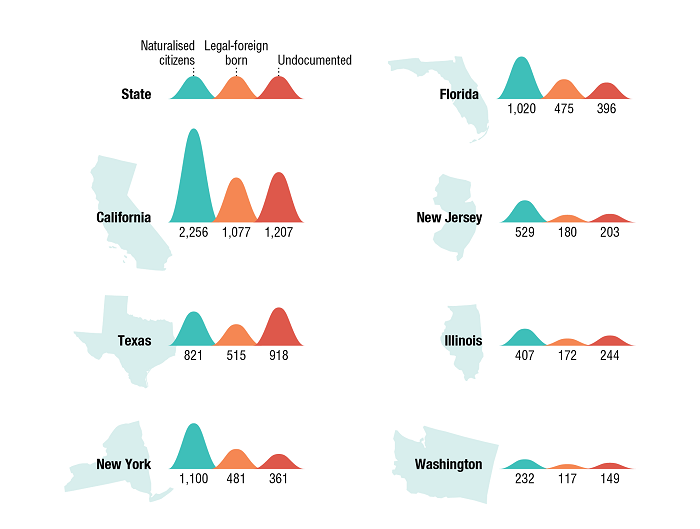

The contradictions highlighted by the pandemic do not end there. When it comes to migrant workers with irregular status, the disjointed nature of public policies is even more disorienting. Nowhere is this better illustrated than the US, where nearly three quarters of all undocumented migrants are working in sectors deemed essential to the nation’s critical infrastructure. These workers are simultaneously ‘essential’ and at daily risk of detention and deportation.

Key workers that are migrants across selected US states (thousands)

More coherent and fairer policies – the first steps towards migration reform

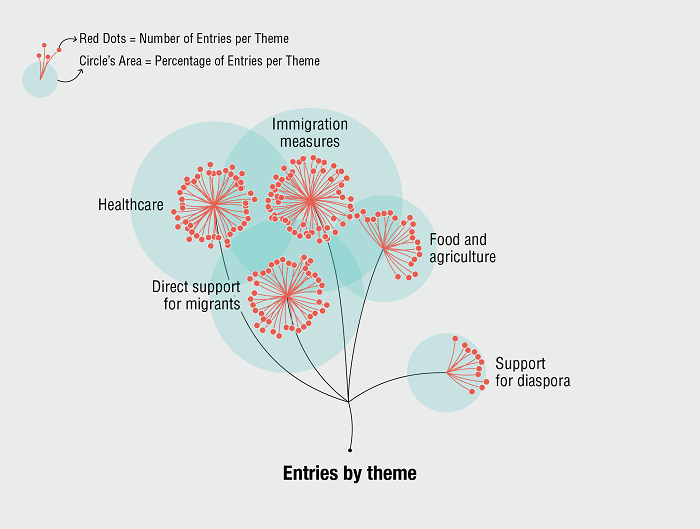

The pandemic has forced countries to confront some of these contradictions. While we have tracked stories on healthcare, food and agriculture and measures taken to support migrants, how countries have dealt with immigration status has emerged as a major story.

A strong thread emerging is how many countries in both Europe and North America have temporarily reformed immigration rules to address labour shortages in the health workforce.

Entries by theme in our data visualisation about migrants' contribution to the Covid-19 response

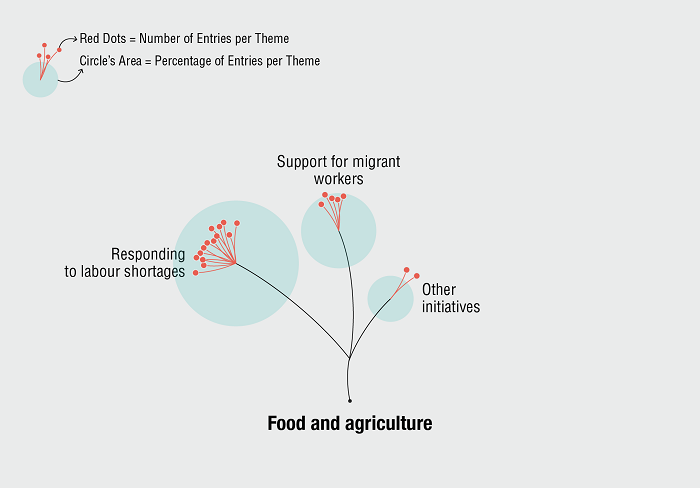

A similar story emerges regarding agriculture. Two thirds of the stories we collected concerning this sector relate to fast-tracking migrants as a response to agricultural labour shortages. From arranging special charter flights, hiring irregular migrants in Greece, or employing asylum seekers without work permits in Germany, these examples illustrate perfectly the need for expanded legal pathways for migrant workers.

Entries for the food and agriculture sector in our data visualisation about migrants' contribution to the Covid-19 response

While countries have quickly brought migrants into their health workforces, efforts ensuring migrants have access to healthcare themselves such as in Colombia, Ireland and Portugal (in Portuguese) appear much less common. Similarly, we found disappointingly few examples of countries (or businesses) providing support to agricultural (and other) workers to improve their living and working conditions. This has not only put workers’ lives at risk, but also the lives of the communities where they live, given reducing the risk of infection is a protective public health measure that benefits us all.

Migrants’ regularisation: a new trend?

Some countries have adopted temporary fixes to address labour shortages in key sectors, others have moved to embrace regularisation of migrants. Some, like Portugal (in Portuguese), have taken significant steps in this direction. Other countries – like Italy, Bahrain and Kuwait – have implemented partial measures. Both Canada and France have adopted specific residency and citizenship initiatives, in recognition of the contribution of migrants to their pandemic response. We may be witnessing a trend towards regularisation, with 2021 bringing Colombia's significant decision to grant legal status and the right to work to Venezuelan migrants for 10 years.

Financial support for migrants

An undoubtedly positive feature of countries’ responses to the Covid-19 pandemic has been the inclusion of migrants in financial aid packages. From Costa Rica (in Spanish) to Tasmania, migrants have been included in payment schemes to alleviate financial hardship. Some countries – such as Ireland and Italy (in Italian) – provide particularly good examples of mainstreaming migrants into new programmes to ensure all are protected from the economic impacts of the crisis.

While examples of direct support for migrants are encouraging, we fear that migrants with irregular status remain overlooked. Our tracking efforts reveal that – apart from a few notable exceptions such as in Ireland, California (subscription required), Chicago and Egypt – migrants with irregular status are rarely included in emergency aid packages.

Increased vulnerabilities in the face of the pandemic

The pandemic has also starkly revealed the risks and vulnerabilities that migrants face. Evidence is accumulating that the particular tasks migrant key workers perform and their working and living conditions expose them to a higher risk of Covid-19 infection. This is a particular concern given migrants often have less access to healthcare. Health vulnerabilities are also exacerbated by the economic impacts of the crisis, with migrants' incomes disproportionately at risk due to multiple factors.

We know migrants have not been sufficiently protected in the face of this global health and economic emergency. It is time to correct this, not just as a matter of gratitude or solidarity, but in recognition of the collective nature of our society and the benefits we all derive from our essential workforce.

Beyond borders: time for a new conversation

At no point has the fundamental contribution that migrants make to our societies ever been clearer. Going forward, there is no doubt that migrant workers of all skill levels will be even more essential in the recovery. We need a new conversation that goes beyond immigration policies centred on border control and quotas and focuses instead on what our communities, cities and businesses really need to thrive after the crisis. We offer four priorities for migration reform based on what we have observed and learnt during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Four priorities for migration reform

- Enhance pathways to regularisation for migrants, in recognition of their vital contribution to essential services.

- Expand legal migration pathways, ensuring safe working conditions for all, to support post-Covid national recovery, tackle shortages in essential workforces and to meet all skills gaps.

- Ensure that migrants, whatever their status, have access to key basic services and social protection.

- Detach out-dated ‘skill level’ requirements from migration policies.

As the pandemic rages on and we hopefully move into a new phase of rebuilding and recovery, there is no doubt that migrant workers will be even more essential. Let us hope the lasting memory of the contribution of migrant workers drives our societies and political systems to properly value and reward their contribution.

Explore all the stories discussed here through our 'Key Workers: Migrants' contribution to the Covid-19 response' data visualisation and our one-year review paper Beyond gratitude: lessons learned from migrants’ contribution to the Covid-19 response.

With thanks to all who have helped to track and report on migrants’ contribution during the pandemic, especially Marta Foresti, Elsa Oommen, Amy Leach, Merryn Lagaida, Kate Rist and Avery Grayson. And with special thanks to information designer Federica Fragapane and developer Alex Piacenti for their innovative design contributions.